Interview with the curator of the new exhibition devoted to limited-edition design and high-end creative manufacturing. Scheduled from 21 to 26 April at Pavilion 9 at Rho Fiera, Milan

Empathetic architecture: designing the city by starting from vulnerabilities

These benches in Vancouver parks open to turn into small shelters for the homeless

From urban measures for the disabled to experimental and academic projects. Empathy and inclusivity can become fundamental principles of architectural and urban design

There is no single definition of empathetic architecture: it is not an actual architectural movement, nor an approach whose boundaries have been defined in a critical and systematic way.

Empathy in architecture rather embodies a quality of design, a specific sensibility and a conscious desire to include and welcome all diversities, special needs, vulnerabilities and different modes of movement in urban spaces.

Empathetic architecture can manifest itself through small devices, details of public space, experiments, provocative projects or initiatives that reveal the potential of new prospects for urban design.

Every project of this type starts with a simple but often overlooked question: how do those who live in these spaces feel?

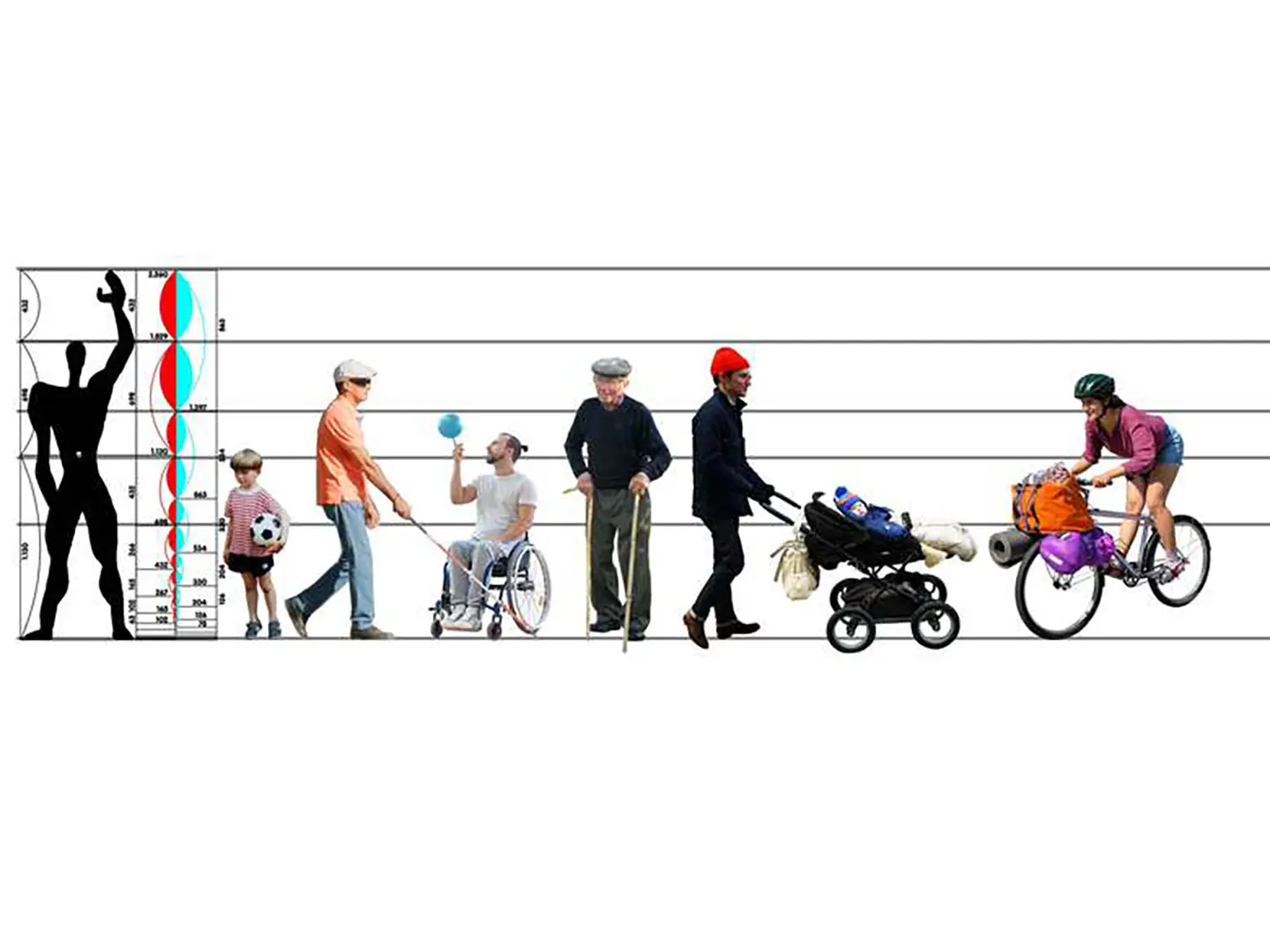

Le Corbusier’s Modulor and its limits: the standard man as universal measure against the real diversity of urban users

Empathy, moreover, is the “ability to deeply understand and share the emotions, thoughts and outlooks of other people, putting ourselves in their shoes without losing sight of our own boundaries”.

Applied to architecture and urban planning, it implies the ability to observe and design the city from the point of view of homeless people, those with disabilities, those who use alternative forms of mobility, as well as non-humans, so expanding the very concept of inclusive public space.

Examples of empathetic architecture

The Architect of the Capitol (AOC) partnered with City Wildlife, a nonprofit organization committed to rescuing and caring for wildlife, to protect the ducklings on Capitol Hill, the historic site of the United States Congress in Washington, D.C. The project involved studying the needs of the animals and creating an inclusive ramp that would enable ducks of all ages to safely enter and exit the large fountain, climbing over the limestone curb.

A ramp for ducks and ducklings built on Capitol Hill, Washington D.C.

During Milan Design Week 2022, architect Stefano Boeri presented the “Bench for those who have a home and for those who don’t”, an example of empathetic and inclusive urban design. Thanks to its generous dimensions and functional design, the seat can be converted into a bed for resting. This experimental furniture is equipped with two multifunctional armrests, which can also be used as a head support, and a mobile panel on the backrest that provides shelter from the sun or bad weather.

The “Bench for those who have a home and for those who don’t” by Stefano Boeri

Finally, in Singapore, an intelligent pedestrian crossing system has been introduced that adaptively regulates traffic the timing of the traffic lights. Seniors and people with disabilities can use their Senior Citizen Concession Card to automatically extend the duration of the green signal, giving them more time to cross streets safely. This inclusive smart city service improves the quality of everyday life and is a technological version of the good old custom of helping old people cross the street.

Road crossings in Singapore, with a slow-crossing device

Empathetic architecture as a main research topic

In addition to isolated cases of empathetic architecture, there are universities and designers that make empathy and inclusivity the core of their approach to design.

A significant example is found in Los Angeles, a city that is facing a rapidly and steadily worsening homelessness crisis. Although the local government considers the implementation of housing solutions a priority, many of its plans will take years to be given practical form. In this context, the School of Architecture of the University of Southern California (USC) has launched the Homeless Studio, an academic project that critically investigates the role of the architect in helping alleviate the housing emergency. The workshop focuses on the design of temporary, mobile, modular and expandable structures, offering a concrete architectural approach to provide alternatives to life on the street and reduce exclusive dependence on government intervention.

Stories

Stories