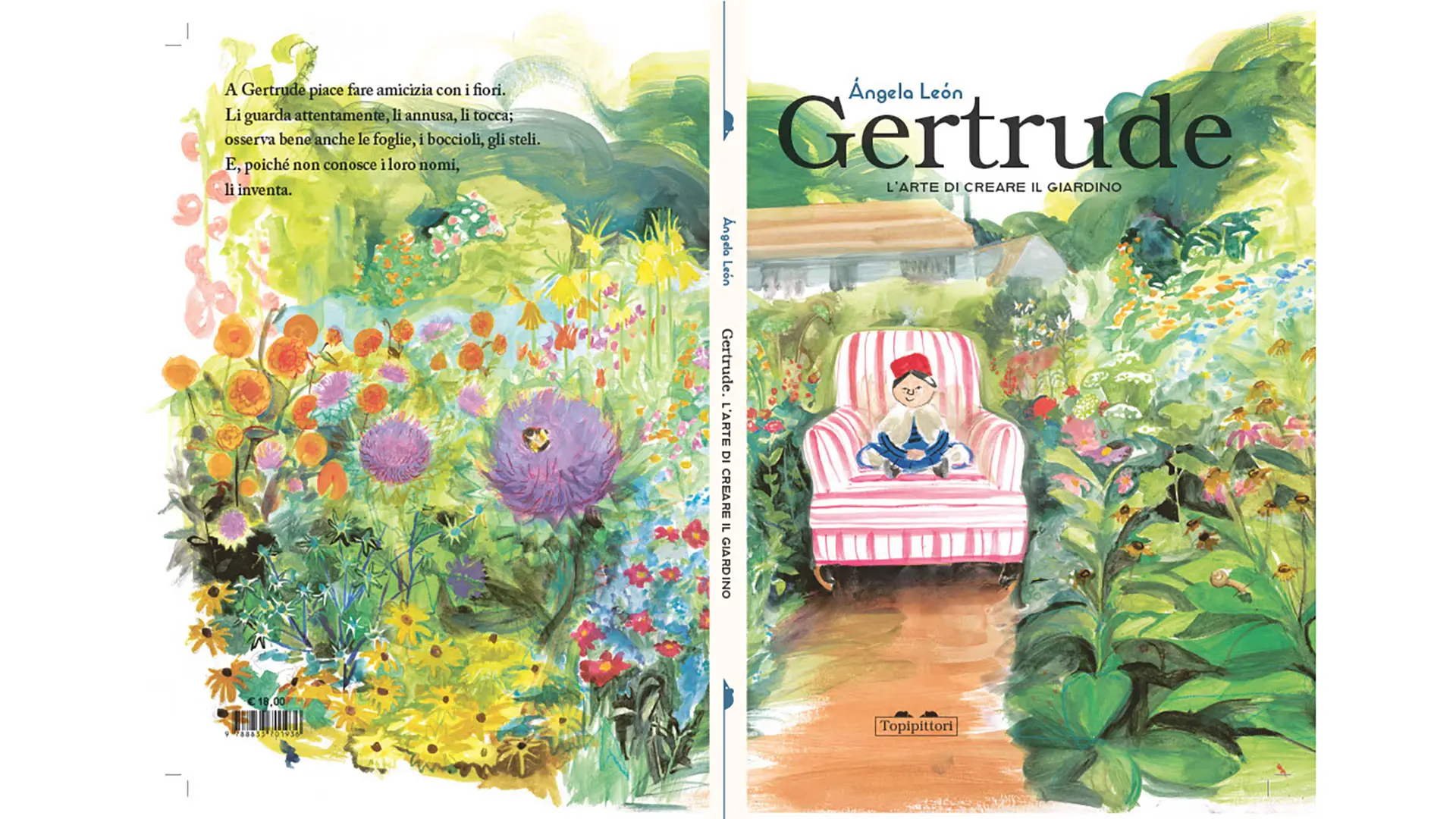

Gertrude. L’arte di creare un Giardino [Gertrude. The Art of Creating a Garden] by Ángela León, published by Topipittori, has just been released. It is the third in a series of books dedicated to extraordinary women who have changed the way we live and inhabit

STUDIOARO, Meditation Gazebo, Denkanikottai, India 2022, ph. Turtle Arts

From energy to the reuse of the existing, a reflection on the principles and perspectives – but also the limits and contradictions – of contemporary sustainable architecture

Does sustainable architecture really exist? Can we really define architecture as “sustainable”? In recent decades, architecture has been called on to deal ever more directly with the environmental, social and economic consequences of its production processes. More than a stable concept, sustainability in architecture is a field in continuous redefinition, reflecting cultural, technological and political changes. In recent years, sustainability has been a term repeated like a mantra for years, used so many times – and often inappropriately – that it has almost lost all meaning.

An interesting insight into the meaning and evolution of the idea of sustainable architecture comes from the architect Giovanni Comoglio, in an article published in Domus and entitled “When sustainability was called "ecology": a journey through the pages of Domus”. Comoglio traces the first appearance of the term in the magazine in a text in January 1997, a moment that “contains all those trajectories that, not too surprisingly, are still central today in designing our relationship with the planet”.

BC architects & studies + Assemble, Lot 8 Design and Research Laboratory, Arles, France, 2023, ph. Morgane Renou

The environmental impact of construction: data and perspectives

If we are looking for the meaning and perspective of sustainable architecture, we need to start from a fact: the construction sector has an enormous environmental impact. According to the 2022 Global Status Report for Buildings and Construction – a publication of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) – the construction industry is responsible for 37% of global CO₂ emissions and consumes more than 34% of the world's energy supply.

Alarming data, destined to grow if structural measures are not adopted on a global scale. Estimates speak of a doubling of the demand for buildings and floor spaces by 2060, especially in Asia, Africa and metropolitan contexts.

Burj Al Babas is a huge unfinished real estate project in Turkey: a luxury village of 732 miniature fairytale-style castles abandoned when the project failed financially

Beyond style: sustainable architecture as a mindset

Starting from this state of affairs, the architectural world has become aware of the need to radically transform the way we conceive buildings, focusing on environmentally friendly materials, reuse of resources, renewable energy sources, concern for the context and the efficiency of processes involved in the use of environmental resources.

The goal of sustainable architecture – also known as bio-architecture or green building – is to minimize the environmental impact of buildings across their whole life cycle, from construction to use, decommissioning and demolition.

Energy-efficient architecture is not a style and does not dictate an aesthetic. It is not a unified strand of architecture, but a design mindset made up of practices, strategies and expedients that have to change and adapt to contexts. The era of universal solutions – often developed by male, white Western designers – now seems to be superseded.

Dorte Mandrup, Icefjord Centre, Ilulissat, Greenland, 2021, ph. Adam Mørk

Energy, materials, reuse: the macro-themes of sustainability

Rather than providing an unambiguous definition of sustainable architecture, it is more useful to identify some macro-themes. Energy management is central and includes the bioclimatic approach – orientation, solar exposure, shading and natural ventilation – and the quality of the building envelope, capable of reducing consumption during the use phase.

These are joined by renewable energy, the efficiency of utilities and systems, the choice of building materials evaluated according to the Life Cycle Assessment, and their place of origin, favoring local supply chains and eco-regional areas. Recycling and reuse become design criteria: mechanical building systems, modularity, dismantling and revaluing of the existing as an alternative to the consumption of land and primary resources.

ecoLogicStudio, Photo.Synth.Etica, a façade installation that incorporates microalgae systems for CO₂ capture, experimenting with the relationship between architecture, the environment and biotechnology, courtesy ecoLogicStudio

Excellent practices of sustainable architecture

A lesson on the complexity of this topic is provided by the work of Dorte Mandrup. In an interview published in Abitare, the Scandinavian architect points out how building regulations and the cultural context profoundly influence the very idea of sustainability. “Building regulations in Denmark are extremely strict, especially on energy use in the management phase, even as early as the seventies, after the oil-price crisis. Today, however, it is equally important to analyze the life cycle of the building by calculating the CO₂ emissions generated during construction and throughout its whole life cycle until it is dismantled”.

This approach is not comparable with that propounded by Diébédo Francis Kéré, whose idea of sustainability stems from vernacular architecture, the use of local materials, passive strategies for climate comfort and the involvement of local communities. A sensibility rooted in the context that won him the 2022 Pritzker Prize.

Sustainability

Sustainability