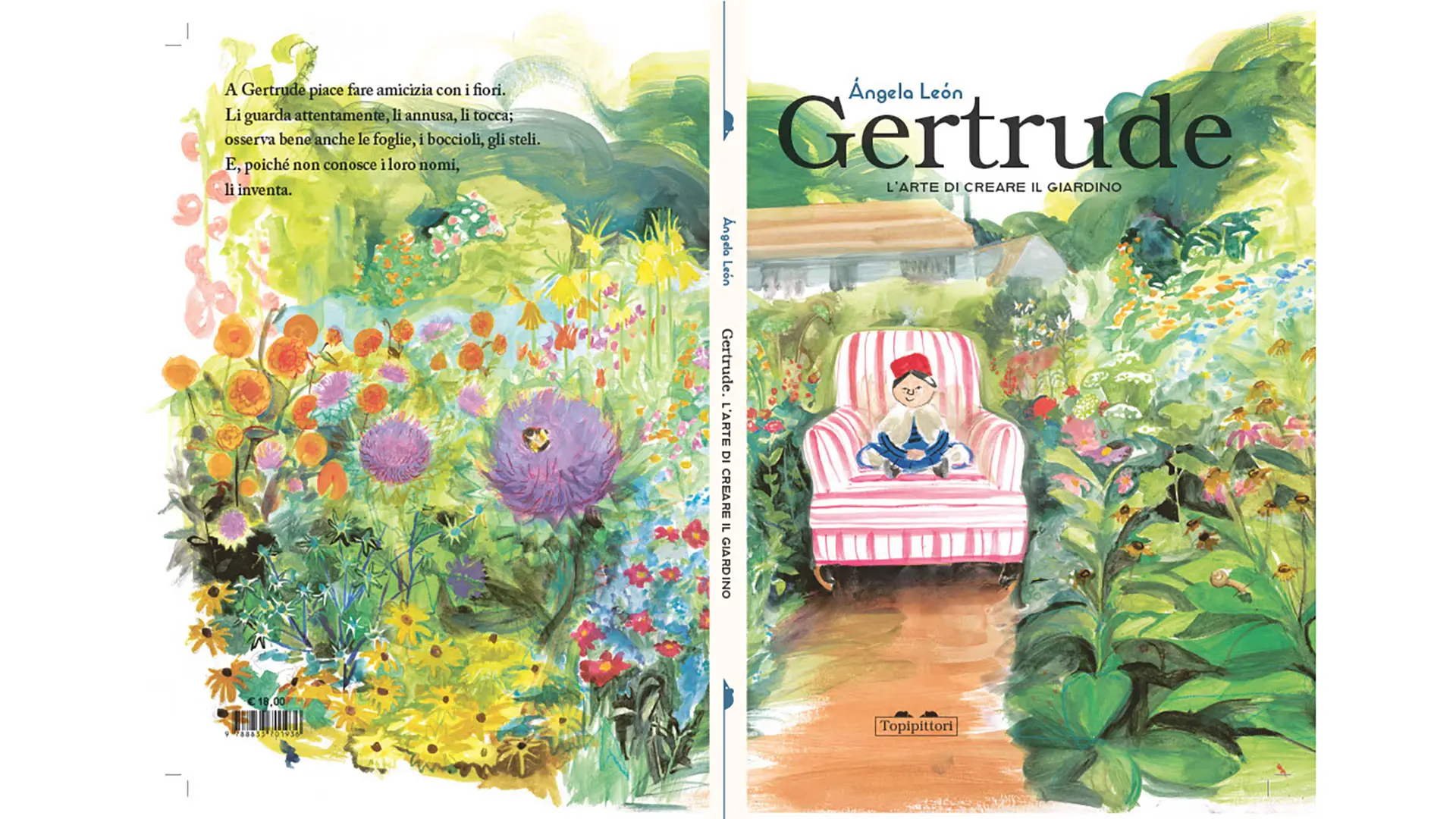

Gertrude. L’arte di creare un Giardino [Gertrude. The Art of Creating a Garden] by Ángela León, published by Topipittori, has just been released. It is the third in a series of books dedicated to extraordinary women who have changed the way we live and inhabit

Magical Nights. The past and present of stadiums in Europe

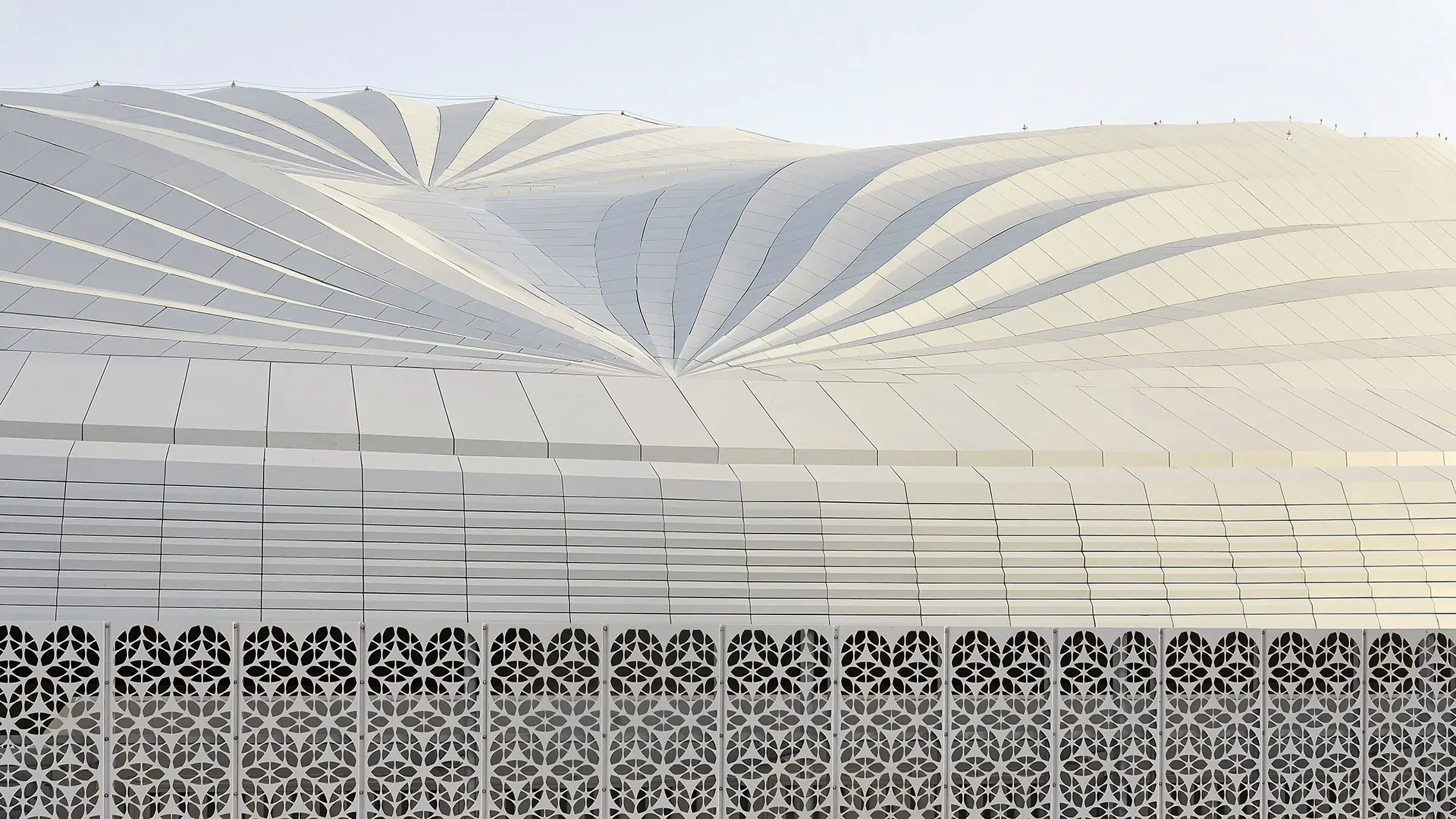

Al Janoub Stadium, Al Wakrah, Qatar, by Zaha Hadid Architects, ph. Hufton+Crow

European stadiums, architectural symbols of collective identity and urban memory, are now facing challenges of sustainability, accessibility and reuse

“Magical nights / chasing a goal / under the sky of an Italian summer,” sang Gianna Nannini in 1989. Football has always been an integral part of the culture of every country, and the spaces that host it – the stadiums – are the most visible reflection of this. Symbols of togetherness and belonging, veritable emotional megastructures, stadiums have long been considered much more than just sports infrastructures. Charged with an almost sacred aura, they are often compared in common speech to modern cathedrals, places where the community gathers to celebrate secular rituals.

So it is hardly surprising that the stadium has always been at the centre of architects’ interest – the subject of university courses (like the one at the Politecnico di Milano) and dedicated exhibitions, such as the one that the MAXXI in Rome is currently hosting (“Stadiums. Architecture and Myth”, 30 May 2025-9 November 2025).

Today, the stadiums of the twentieth century are back at the centre of the debate for two main reasons. On the one hand, the continuous urban expansion in Europe has ended up incorporating facilities built in peripheral areas, as is also happening with cemeteries and factories. This has forced cities to rethink the management of spectator and traffic flows at times of maximum use. On the other hand, many of these structures, although they were designed by great architects, are suffering from a structural rigidity that limits their adaptability to new functions. The difficulty of hosting events other than football – concerts, spectacles and other sports – is revealing their limits, further compounded bythe use of materials that are now obsolete, such as reinforced concrete, a symbol of a heroic season but far removed from today’s technological and environmental standards.

A case in point is the Louis II Stadium in Monaco, designed by Henri Pottier in 1985. Built not far from the sea and the city centre, it is one of the most significant works of European sports architecture, but also an example of the difficulty of updating structures built in a different era. Monumental and iconic, the stadium is now undergoing renovation to improve accessibility and safety. Another significant case is the Municipal Stadium of Braga, designed by Eduardo Souto de Moura in 2003. Hewn out of the rock of a former quarry, its positioning and integration into the landscape made it a masterpiece of contemporary architecture. But even here, twenty years later, new questions are being raised: how to rethink these monumental structures with respect to the changed social, environmental and technological needs?

Many of the stadiums built during the twentieth century are now in a critical position. Although recognized as cultural assets (only in part), their survival is threatened by poor functionality: a lack of flexibility, technological inadequacy, and poor levels of security and inclusion. Almost all of them were tailor-made for a male public, ignoring diversities of gender and age. It is precisely on this point that large international studios, such as Zaha Hadid Architects and Populous, are focusing, committed to designing stadiums that are more accessible and safe for all.

Apart from the social issues, environmental sustainability is also at stake. Contemporary architects are replacing reinforced concrete with low-impact materials, such as cross-laminated timber (CLT), recycled steels, and biocompatible plastics, to reduce the embodied carbon in structures. Construction processes are also evolving: the use of prefabrication and elevated assembly makes it possible to reduce time, costs, and waste, making buildings more efficient and reversible.

There is no shortage of examples of these new-generation stadiums. The Tottenham Hotspur Stadium in London (Populous, 2019) is a model of versatility. It has a retractable pitch that enables it to switch from association football (aka soccer) to American football in a few hours. The Allianz Arena in Munich, designed by Herzog & de Meuron, with its translucent ETFE envelope, has become an icon of sustainability and architectural spectacularity. While the Al Janoub Stadium by Zaha Hadid Architects, built for the Qatar 2022 World Cup, introduces a fluid and aerodynamic vocabulary inspired by dhow sails, combining advanced engineering and a concern for the climate.

At this point inevitably a question arises. What will become of the “obsolete” stadiums, no longer capable of responding to the needs of contemporary society? Is it possible to save them through renovation, or will the desire – as in the case of the Meazza stadium in Milan – to replace them with new buildings prevail? The answer is not simple. What should be preserved, in addition to the architectural value, is the collective memory that these places embody as identitarian symbols that tell the story of whole generations. Demolishing them would mean not only erasing a cultural heritage, but also generate a huge environmental impact in terms of CO₂ emissions.

With sustainability a priority, demolition should be the last option. The stadiums could be redesigned as multifunctional centres: venues for cultural events, fairs, concerts or alternative sports, adaptable and permeable to the urban fabric. A model that recalls, on a monumental scale, the recovery project of the Scalo di San Cristoforo in Milan, where the project by OMA and Laboratorio Permanente will turn Aldo Rossi's unfinished station into a multifunctional hub open to the city.

This is not a utopia, but a concrete possibility that requires political will, institutional vision and financial investments. Every stadium involves complex interlacing interests – sporting, commercial, cultural – but it is precisely for this reason that a shared reflection between architects, institutions and citizens appears more urgent today than ever. Rethinking the stadiums of the past does not mean looking back with nostalgia, but imagining how memory can become infrastructure for the future.

Stories

Stories