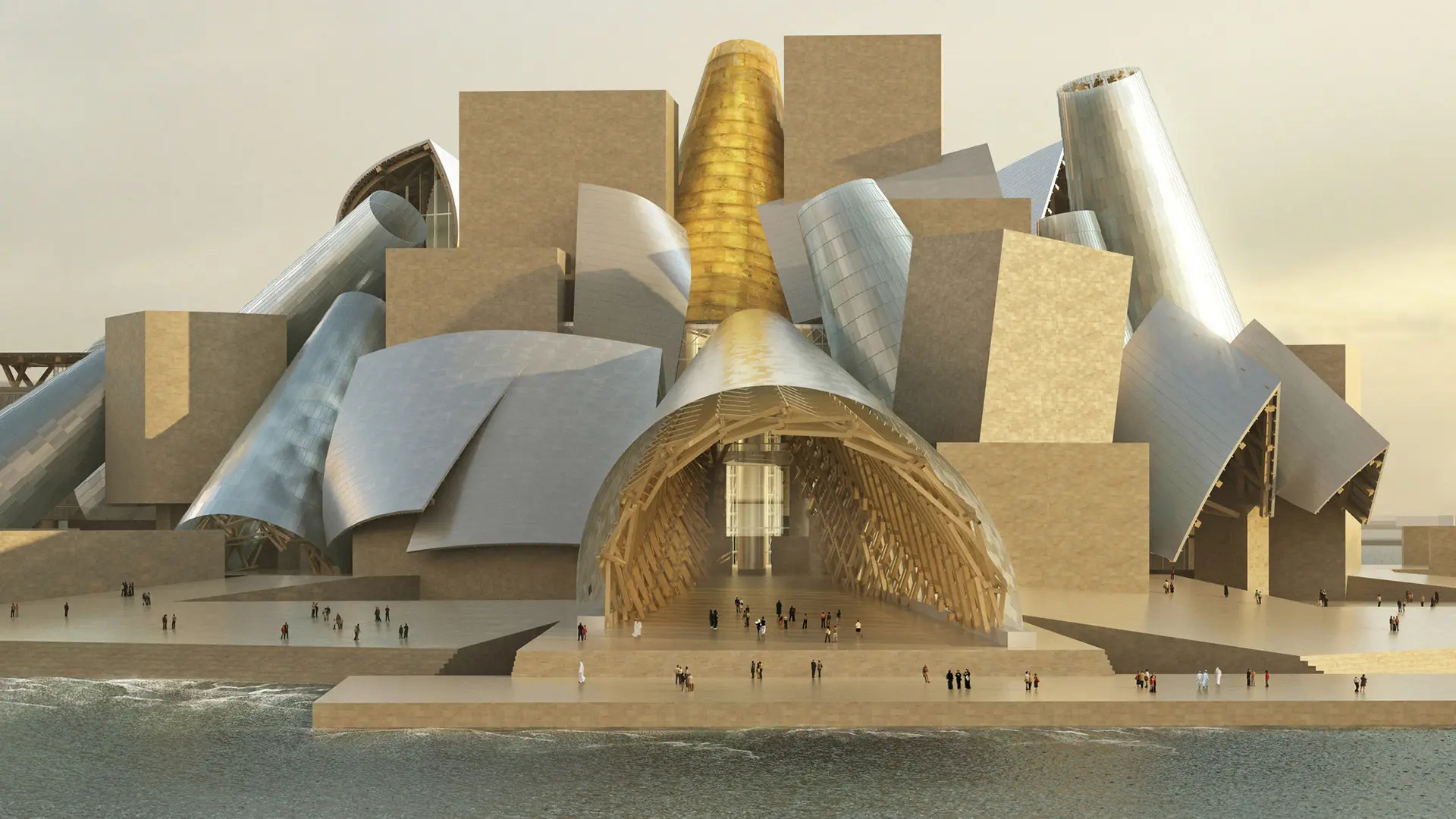

From BIG to David Chipperfield, Frank Gehry to Snøhetta: a world tour of the best buildings set to open in 2026

Rifugio Carlo Mollino - Photo Bruno Gallizzi

Conquering dizzy heights with altitude-defying projects and all their climatic and atmospheric challenges. Following on from the more recent examples, a well-deserved tribute to historic refuges by Charlotte de Perriand, Franco Albini and Carlo Mollino.

Only a diehard fan of the mountains such as Charlotte Perriand could have “invented” a mobile refuge back in 1936, which saw the light two years later as the fabled Refuge Tonneau, created with Pierre Jeanneret. Reconstructed by Cassina from original sketches and notes for the week of Salone del Mobile 2012, it is now at the Meda headquarters. The shelter (3.80Ø x 3.92h m) provides a welcome resting place for serious mountaineers. The dodecahedron structure was inspired by a children’s merry-go-round photographed in Croatia, while the space shuttle shape and portholes were precursors for projects carried out decades later, such as the 2002 Concordia stations in the Antarctic and the Mars Society Desert Research Station. The aluminium frame was chosen for its lightness, the shape was designed to be wind-resistant, the stilts were chosen to ensure stability even on the most uneven and steep terrain and the porthole windows were designed to keep out the cold. The pine interiors chime with the natural environment, and serve to heighten the refuge’s welcoming feel. Each piece of furnishing, from the heater inside the central pole, to the chairs that can be turned upside down to become beds, the tiny kitchen down to the bucket complete with tap over the sink for melting snow into running water, is an expression of practicality combined with good looks.

Refuge Tonneau - ©StefanoTriulzi

Franco Albini was another Master who took on alpine architecture. He and Luigi Colombini designed the Pirovano children’s hostel/refuge situated on a steep slope in Cervinia, between 1948 and 1952. The bottom three floors of the building sit against and are partly built into the side of the mountain, while the two upper floors are completely above ground. It is a fine example of the ability of mid-20th century Italian architecture to interweave modern and traditional architectural themes by using local materials and reinterpreting autochthonous building techniques such as the blockbau method of building houses from interlocking specially carved larch logs.

Pirovano children’s hostel/refuge, Franco Albini - Courtesy Fondazione Franco Albini

The original project for Casa Capriata was seen as a manifesto for experimentation with building materials and techniques during the Fifties. Plans for the eco-sustainable wooden refuge were drawn up by the Turin-born architect Carlo Mollino for the 10th Triennale di Milano in 1954, but disagreement between the sponsors meant that it was never actually built. The idea of bringing the plans to fruition started as a cultural project as part of the celebrations for the anniversary of Mollino’s birth, and then became a research project and a reality in 2010 under the name of Rifugio Carlo Mollino, thanks to the efforts of a team of researchers at the Department of Architecture and Design at Turin Polytechnic University led by Professor Guido Callegari, and by the Comunità Montana Walser. A “lightweight wooden structure” raised off the ground, a reference to the local Walser buildings, became an experimental building in the Weissmatten ski area, at Gressoney Saint Jean, in which the architectural, structural, technological and engineering aspects were reworked in keeping with the design criteria set out by Mollino, resulting in an energy efficient building with innovative components and construction systems, consistent with the original building/manifesto. Great care was taken over the interiors, such as the rubber flooring contrived with a product by Ettore Sottsass, whilst the interiors are furnished with pieces designed by Mollino from the Zanotta collection.

Rifugio Carlo Mollino - Photo Bruno Gallizzi

Lastly, for devotees of high altitudes, the exhibition Refuges Alpins. De l'Abri de Fortune au Tourisme d'Altitude is on at the Musée Dauphinois in Grenoble until 21st June, illustrating two hundred years of architecture on the most impervious summits.

What does the future hold for high altitude architecture? A prosperous and respectful one, hopefully. Meanwhile, as Reinhold Messer suggests, we should approach mountains “in a different way, letting our spirit fly above every peak.” Perhaps even our imagination will continue to know no bounds.

Stories

Stories