Wood transforms the kitchen space with craftsmanship, technology, and continuity with the living area

photo by Delfino Sisto Legnani

For Andrea Trimarchi and Simone Farresin, the purpose of design is to produce reflections and imagine alternative avenues. Materials, with their cultural, social and political reach, constitute their main vocabulary.

Andrea Trimarchi and Simone Farresin met while studying at the ISIA Design Institute in Florence, midway between their birthplaces – the Veneto and Sicily – and decided to continue their studies outside Italy, at the “legendary” Design Academy in Eindhoven. After taking their diplomas, they established themselves definitively in Holland, setting up their own studio with the intention of looking at and making design following their own instincts rather than the usual commercial routes, experimenting, focusing on conceptual research and seeing design as a process of discovery and knowledge-building which, step by step, informs the essence of a product.

Formafantasma seemed a good name for a practice that straddles craft and industry, manufacturers and users, with the emphasis on materials rather than objects, process rather than form. Materials – with all their cultural, social and political connotations – form the main vocabulary for their design. Ranging from bread to coal, from fish skin to wood, from sea sponges to lava, they trigger the creative process of dialogue and analysis resting on a stack of images, suggestions and sensations that shape a new product which, therefore, only emerges at the end of this lengthy journey, as a “phantom form.” As to production, alternative, non-serial and non-industrial methods are envisaged, channelling the retrieval of ancient processes, the relationship between tradition and local culture, tackling issues such planned obsolescence. The starting point is the assumption that the task of design today is not so much to design new products but to trigger reflection and spark “other,” alternative approaches.

Basically, it is a studio that demolishes preconceived ideas, pre-established rules, in favour of an emotional approach, dialogue and process. It is extremely attractive. To everyone. Even the manufacturers. Their portfolio is star-studded, to say the least. They have worked for Fendi, Max Mara - Sportmax, Hermès, Droog, Tappeto Nodus, J&L Lobmeyr, Gallery Giustini / Stagetti Rome, Gallery Libby Sellers, Established and Sons, Lexus, Krizia International and Flos, to name but a few. They take part in Dutch Design Week, the Salone del Mobile di Milano, Abu Dhabi Art, ICFF in New York, and Design Miami/Basel. Their objects have entered the collections of MoMA and the Metropolitan Museum of New York, the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, the Chicago Art Institute, the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris, the TextielMuseum in Tilburg, the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, MUDAC in Lausanne, the MAK Museum in Vienna, the Cartier Foundation in Paris, the Centraal Museum in Utrecht, Les Arts Décoratifs and CNAP in Paris.

In a way. When we chose the name, we did it intuitively and before we officially set up our studio. Over time, however, it’s become steadily more consistent with our concept of design, which favours process and contextual research over formal research. In that sense, form is the consequence of a process. It changes.

The work at the studio is steadily going in two different directions. The first is exclusively related to research, with a more radical approach; the second is more commercial. Needless to say, one approach can influence the other. Clearly compromises have to be made to keep a studio going. The aim of our work is to get to grips with how the discipline of design can evolve over and above modern dynamics and thinking, which led to the issue of ecological self-destruction.

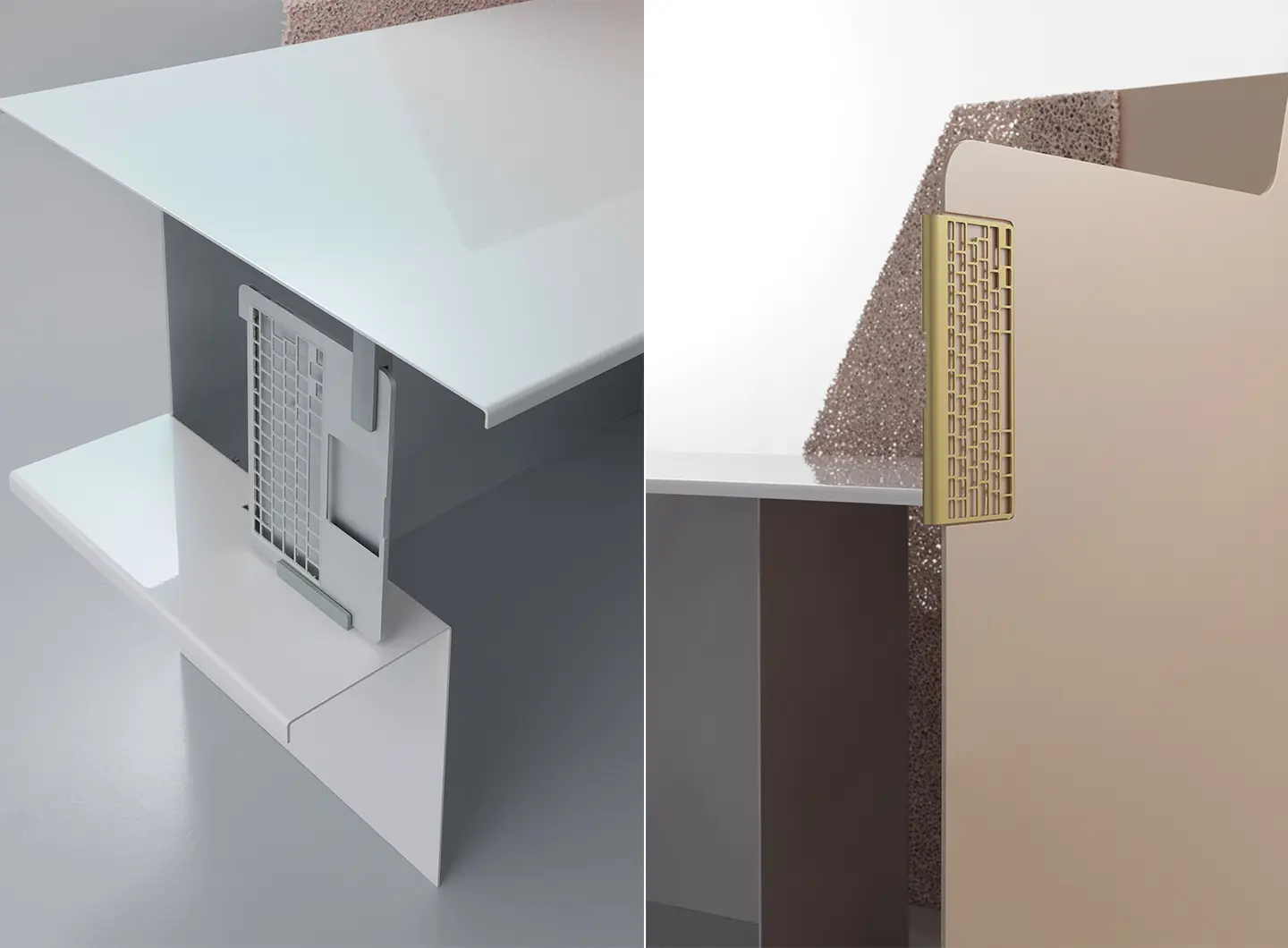

Absolutely. With Ore Streams we focused on the electronic waste recycling industry. As we know, recycling is a short-term solution. It does not involve rethinking the financial situation but about how it evolves. Cutting waste is one of the main parameters for guaranteeing economic proliferation. In any case, as designers it’s important to operate at this level as well. What we need increasingly is to have a multitude of possibilities, more than one single solution, which in reality does not exist. So one can operate on a short, medium and long term scale. The latter calls for visionary ideas alongside what appears to be doable.

The concept of achievability is another reminder of the parameters dictated by economic expansion based on growing consumption. If we see it as Utopian, that means that as human beings our collective imagination is very blinkered and that we accept that our species will become extinct. Probably the greatest Utopia is that of economic expansion based on growing consumption. Our resources are quantifiable and limited. Human needs and desires are infinite. Perhaps the greatest Utopias that have never come to fruition are those of capitalism and a free market.

Investigative and intuitive at the same time.

There’s not so much emotivity when we’re working, on the contrary there’s a lot of intuition. We have no idea whether what we are doing counts as poetry.

It doesn’t. We love what we do but we have fun when we go out with friends, have a drink, watch a film. We see what we do as work and that calls for responsibility, reflection - work, basically. There is a frivolous element to fun (which is part of life) which we don’t see as having a place within the concept of work, which is bound up with passion and love.

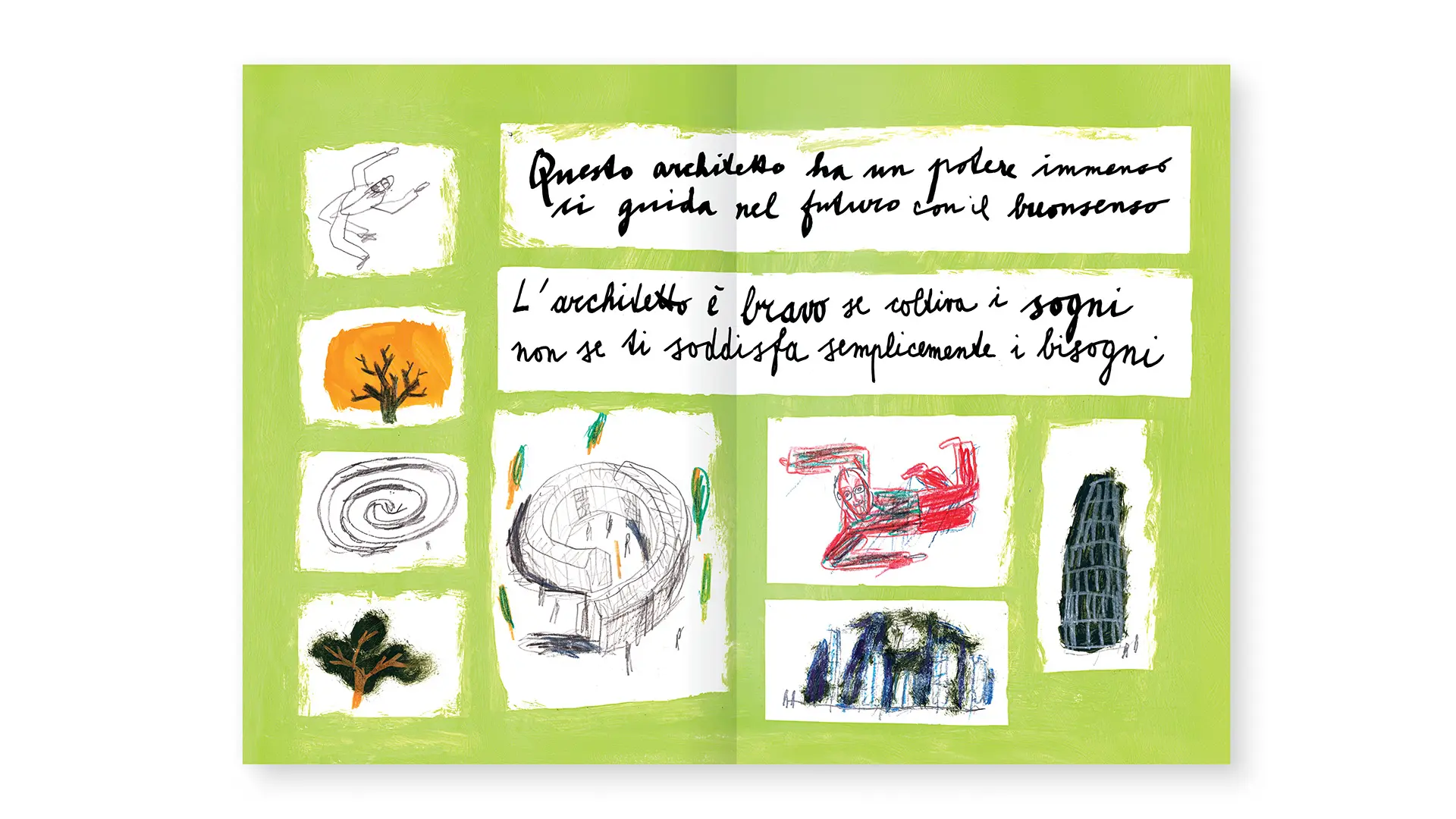

4 children’s books to explore houses, lost objects, and architectural wonders

Some children’s books go beyond wonderful illustrations and clearly deliver a strong message. The titles in this selection invite young readers to look at the world with the eyes of great architects, dream up incredible homes, find lost things. Why? To learn a truly meaningful skill: the ability to recognise the beauty around us, and to understand how to take care of it

Stories

Stories