For the 64th edition of the Salone del Mobile, Maison Numéro 20, the Parisian agency founded by Oscar Lucien Ono, designs an immersive narrative installation that rewrites the codes of luxury and hospitality as a theatrical and sensory experience

La tradizione del nuovo, as told by Marco Sammicheli

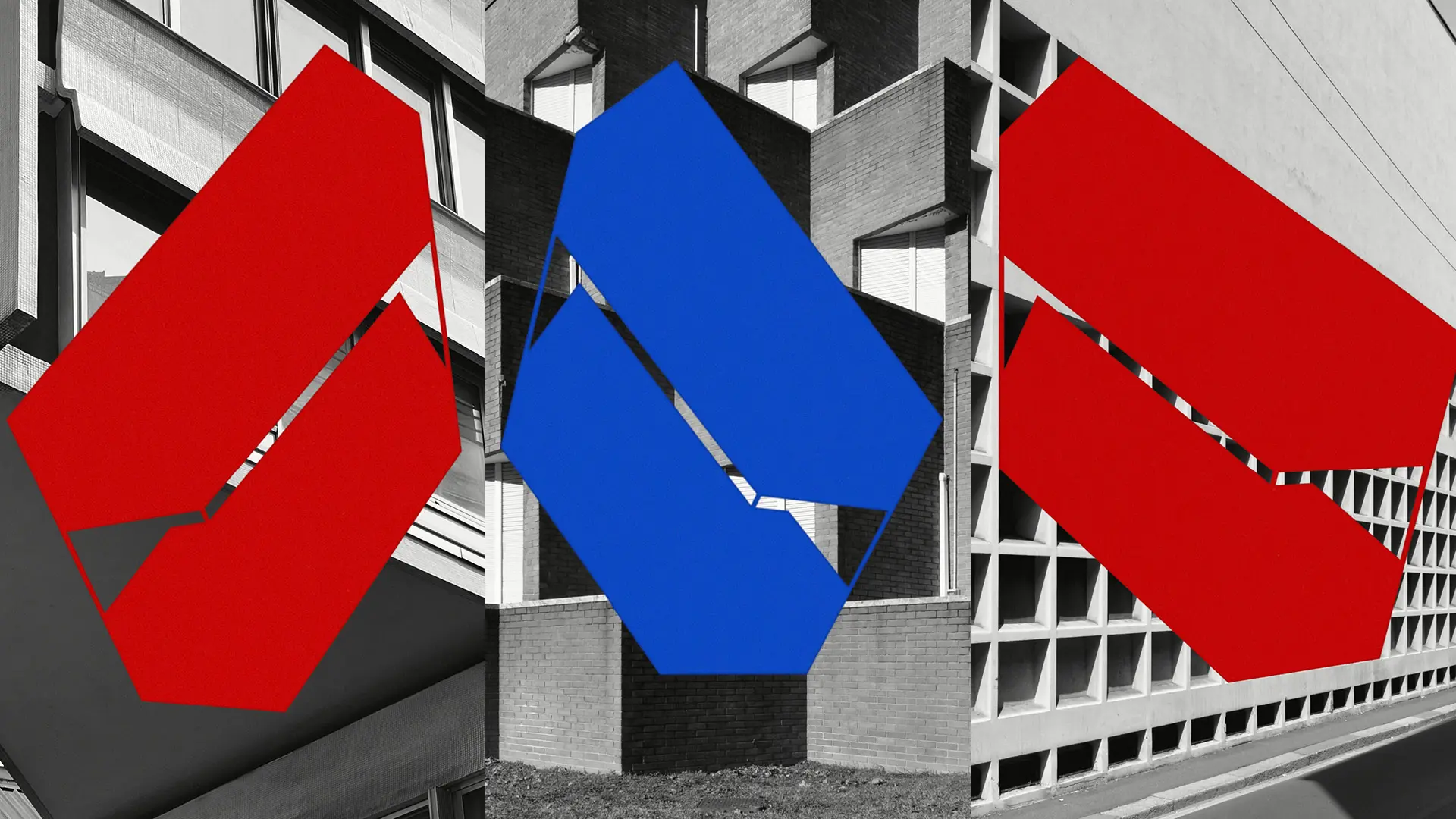

La Tradizione del Nuovo, Padiglione Italia, XXIII Triennale. Ph. dsl studio

The curator of the Italian Pavilion at the 23rd International Exhibition explains why the compulsion to explore has always driven Italian design, the tool harnessed by designers and industries to “grapple with contemporaneity”

The theme of the 23rd Triennale Exhibition, Unknown Unknowns, is designed to introduce possibly now forgotten, ancient ingredients back into the recipe for the way in which we think about the unknown – astonishment, opportunity and emotion.

Marco Sammicheli, curator of the design, fashion and craft section of Triennale Milano and Director of the Italian Design Museum, has curated the Italian Pavilion exhibition, La tradizione del nuovo, which casts an enquiring look at the Triennale exhibitions that took place over the last 30 years or so of the last century, hunting down projects that took on the challenge of contemporaneity (at that time), experimenting and pushing the boundaries of design, planning and industrial production a little further.

We can expect a great deal of unknown things, also in the years ahead. Not the sort of unknown, given the contingencies, that is easy to imagine with much enthusiasm – climatic disasters that are now only containable, perhaps, and the ensuing migrant crises, a political balance shattered after 70 years of Western stability, and the usual sovereignisms in charge. It’s a future – and an approach to the unknown, or to the as-yet unknown – that has now changed, compared with the enthusiasm and expectations of the Eighties, Nineties and early Twenties.

As the visual identity of Unknown Unknowns. An Introduction to Mysteries, with its darkness and those planets shows, pushing our imaginations and planning a little further than the contingencies we’re likely to face on earth in the coming years and setting our horizons a little further, is one of the crucial tools for looking at this future. In some ways a celebration of utopia, rather than dystopia.

This celebration is echoed in the Italian Pavilion at this Triennale with La tradizione del Nuovo, curated by Marco Sammicheli. Not planets, lunar modules, meteorite dust or biospheres for carrying life into space, but a series of doors with strange objects applied to them. The installation by the Zaven studio – a duo composed of Enrica Cavarzan and Marco Zavagno who were responsible for the entire exhibition display – was inspired by the book Invece del Campanello (Instead of a Doorbell), by Bruno Munari and Davide Mosconi, who invented a series of curious, engaging devices for knocking on a number of doors behind which certain particular personalities would be hiding.

La Tradizione del Nuovo, Padiglione Italia, XXIII Triennale. Ph. dsl studio

The exhibition contains hundreds of objects and projects from the Seventies to the late Nineties, in a bid to understand just how Italian design has tackled the challenges of the unknown and imagined futures - and therefore utopias - that were unknown or had not yet become manifest, across the decades.

“This is a research-based exhibition,” says Marco Sammicheli, curator of the Pavilion, who spent months sifting through the Triennale archive, meeting people, and tirelessly visiting archives and designers’ studio. As he explains: “This is an exhibition for which more than 70% of the material comes from the Triennale archives, from our collections, but all of this has come together thanks to the meetings. Exhausting meetings, carried out in tandem with the assistant curator Viviana Fabris, involving designers, photographers, entrepreneurs and collectors, from Guido Antonello to Massimo Cirulli to corporate museums.”

The museum itinerary takes two parallel routes: on one hand there’s a chronological history of the Triennale exhibitions held from 1964 to 1996, showing the evolution of issues that design and architecture have had to contend with, and on the other an exploratory thematic path through the galaxies, as it were: gravity, the Eighties movements, the “men in tin cans,” the music …

Now-familiar objects such as the long ‘giraffe necks’ of the Artemide Tizio lamp by Sapper, the sinuous forms of Cini Boeri’s BoboRelax for Arflex, and the rounded taps in Pedrizzetti’s I Balocchi series for Fantini are shown as they were right at the beginning, not once they were affirmed: open challenges, explorations into the shape of objects, attempts to imagine a different future for a society which, right now, is clearly in need of one.

“Every single time there was a desire to grapple with contemporaneity with something not yet legitimised by an institution or a museum,” explains Sammicheli. The Triennale exhibitions over the last few decades, profoundly different to the latest ones, went a long way in this direction: “Until the Nineties, this was a place that came to life and then subsided every three years, it had no collection or exhibition programme of its own, which meant that there was time to devise and put together things that often proved disruptive.”

La Tradizione del Nuovo, Padiglione Italia, XXIII Triennale. Ph. dsl studio

This isn’t an exhibition about Milan, but Milan is inevitably a major centre of gravity. “What didn’t happen at Triennale largely happened here in this city, so there was a relationship built on proximity and dialogue between the institution and the input from outside.” It was an exchange relationship that, one way or another, produced results – just as every dichotomy, involving encounter or clash – ought to do: “Often the institution found what was going on outside hard to swallow, yet equally, those on the outside subsequently sought the legitimisation of the institution.”

As the years and the exhibition unfold, one can see how the issues the designers, and also the industries, had to contend with altered – perspectives changed radically between the late Seventies and the early Eighties. Memphis came into being in Milan’s Via Manzoni, Alchimia presented its Infinite Furniture design, “an object that was meant to demolish the middle-class ideal of home, as well as being a piece of furniture as poetic as it was reassuring, at the Polytechnic University,” as Sammicheli describes it. As Aldo Cibic said about Memphis, design was taking a break from functionality. The horizon of the field of research, the unknown, had until then been visible – then from 1980 onwards it was wiped out. “It was a time of great solidity for the industry and freedom from the way things had always been done, so everybody felt buoyed up by being able to break into worlds they would never previously have contemplated. When you try and historicise something that’s over, you feel able to manage and contain it, but when these things happened, the critics and the general public were all for them. People were open-minded: they didn’t know how things would turn out.”

The 20th century innovations being showcased in 2022 in the Italian Pavilion have familiar faces and voices, but it’s easy to still see them for what they would have been then: leaps in the dark, visions, attempts to change the world – a bit. Through these products, The Tradition of the New unwraps the people who invented them, in particular. As Sammicheli concludes: “It’s a historical exhibition, but it is also designed to prick the consciences of current designers. First and foremost, designers are not interpreters, they are intellectuals who study society.”

Salone Selection

Salone Selection