Gio Ponti amid architecture, design and industry: from the Pirelli skyscraper to Domus, to furnishings reinterpreted through archival work

Beatrice Leanza: “Museums must be able to evolve into civic and social activation platforms”

Beatrice Leanza - Ph. Diana Tinoco

In her latest book, the Italian curator explains why museums need to change. To become epicentres for research and inclusion for the entire production chain in architecture and design

Beatrice Leanza has never lacked the ability to build bridges in order to gather stimuli and promote a plural, participatory vision of design. From Beijing, where she lived and worked for 17 years, as creative director of Beijing Design Week among other things, the Italian curator has brought her energy to bear on design guided by approaches that are not necessarily traceable to the paradigms of the western world. Her subsequent experiences at the helm of international museums such as MAAT in Lisbon and MUDAC in Lausanne have made her one of the most interesting contributors to the debate around design institutions and exhibition formats today.

In her latest book, The New Design Museum. Co-Creating the Present, Prototyping the Future (Park Books, 2025), Leanza leverages her experience to discuss the identity of museums in the field of design and architecture, including conversations with leading international curators such as Aric Chen, Lucia Pietroiusti, and Jan Boelen. Institutions, according to Leanza, are now being called to rethink themselves in order to respond to the multiple challenges of the present. In a conversation with the author, we endeavoured to explore the reasons for this changed scenario, and to understand how rethinking design museums could create opportunities and stimuli for the entire design production chain.

The simplest way to answer your question is probably to explain why I wrote this book. I did it primarily because I felt an urgent need to bring back at the heart of the social conversation the importance of places that host, produce, preserve and archive culture, particularly – as the title The New Design Museum evokes – those dedicated to design and architecture at large. The urgency is due to the fact that, the challenges of our time, have given life to new forms and areas of knowledge. The 21st century is profoundly different from the preceding one, and given that design practice and discourse have transformed, so too should the institutions that harbour it. The museum, a legacy from late 18th century Europe, cannot remain a material repository of artefacts, it needs to evolve into a civic and social activation platform capable of responding and reflecting on the new fields of intervention of contemporary design.

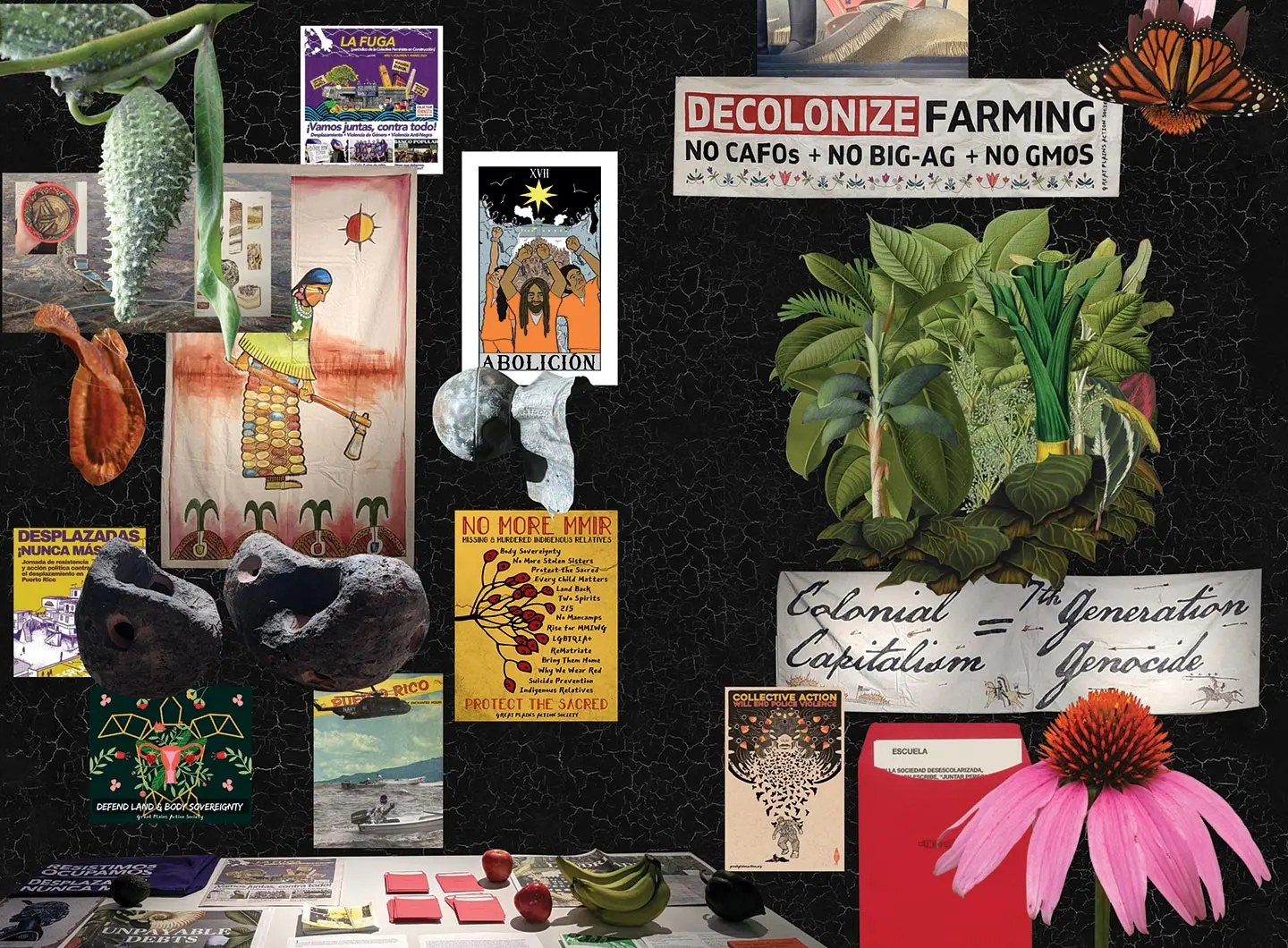

The scope of design has moved beyond the production of finished products and 'solutions' to also encompass the analysis, research and exploration of the processes that go into producing design knowledge and its outcomes, be these products, services, domestic or public spaces. In the book, I identify three macro-factors that have impacted design across the 20th and 21st century. The first is biocentrism, which moves beyond the anthropocentric imperative of design centring on or paying service to the all important ‘human factor’, to look at an increasingly expanded world. Biocentrism invites us to work with nature rather than extract from it, mitigate the impacts of our practices and adapt to the conditions we have created. Biocentrism is also an invitation not to read history as the result of western trajectories of development imposed by dominant political regimes, or directly inherited through the violent mechanisms perpetuated by our colonial past.

Another fundamental characteristic is decentralisation – or rather the emergence of geographically distributed networks of actions and initiatives which, despite their geographical distance share common ambitions and values and battling for socio-economic equality, that is access to life-supporting systems and resources. This makes for a much larger remit and ambit of intervention—that is for whom we design and why. The third characteristic is hybridity, or rather the fact that we’re no longer living in a reality based on dualisms, on binary oppositions such as nature/culture, analogue/digital, or man/woman. The design of our spaces, shared environments, of services, products, practices and the new forms of knowledge, are no longer based on these dualities. Design and design thinking are much broader and less linear, they do not necessarily materialise in the production of, I repeat, a finished object, but are focused on the processes and rituals that define and operationalize our global collectivity.

To start with, we need to demolish the idea that exists something like “a general public”: the public is not one but many and museums should – and can - become many things for different people. There is no “solution-fits-all” scenario, nor indeed a single criterion of evaluation that can be applied simply based on ticketing or click metrics. I believe that programming should always be tailored to the history of each specific institution and the communities to which it speaks and belongs to, embodying the way it wishes to partake in contemporary social debate . I also think that museums cannot simply be places of entertainment – the greatest enemy of cultural institutions nowadays is edutainment. I say this because one of the things I always go back to is one key tenet of Pontus Hultén, the iconic director of Moderna Museet in Stockholm and the Centre Pompidou in Paris, who said that the only relationship a museum should really concern itself with is one of trust with its own public, knowing how to inspire and provoke it in equal measure.

What Brendan says is absolutely true – it’s a subject we have discussed a lot, and which is very familiar to people who, like me, have spent most of their lives in non-western contexts. With the transition to the 21st century, the global world as the West had conceived of it has been completely redrawn, and a fundamental factor in this transformation has been China's rise to global power. That was the moment when the limitations of globalism— with its promises of a united world without borders, of a fluid exchange of people, ideas and goods — became apparent. However, this shift in the geopolitical axis has also had a positive effect: it has confronted the West with different visions of the world, alternative social constructs, different ways of understanding collectivity, the common good, the relationship between people and power, the relationship with history... and much more. So if we consider design as a form of knowledge, a practice, a crosscutting and meta-disciplinary form of knowledge — that is, capable of connecting different fields, from the arts to the sciences, to technology and philosophy — then yes, a museum dedicated to this particular form of knowledge can and must take an active role in cultivating these connections and in critically reflecting on our time.

Stories

Stories