Everything you need to know about the 64th edition: dates, times, tickets, the return of EuroCucina / FTK – Technology For the Kitchen. And then the International Bathroom Exhibition, and the absolute novelties such as Salone Raritas, Salone Contract and the installation “Aurea, an Architectural Fiction”

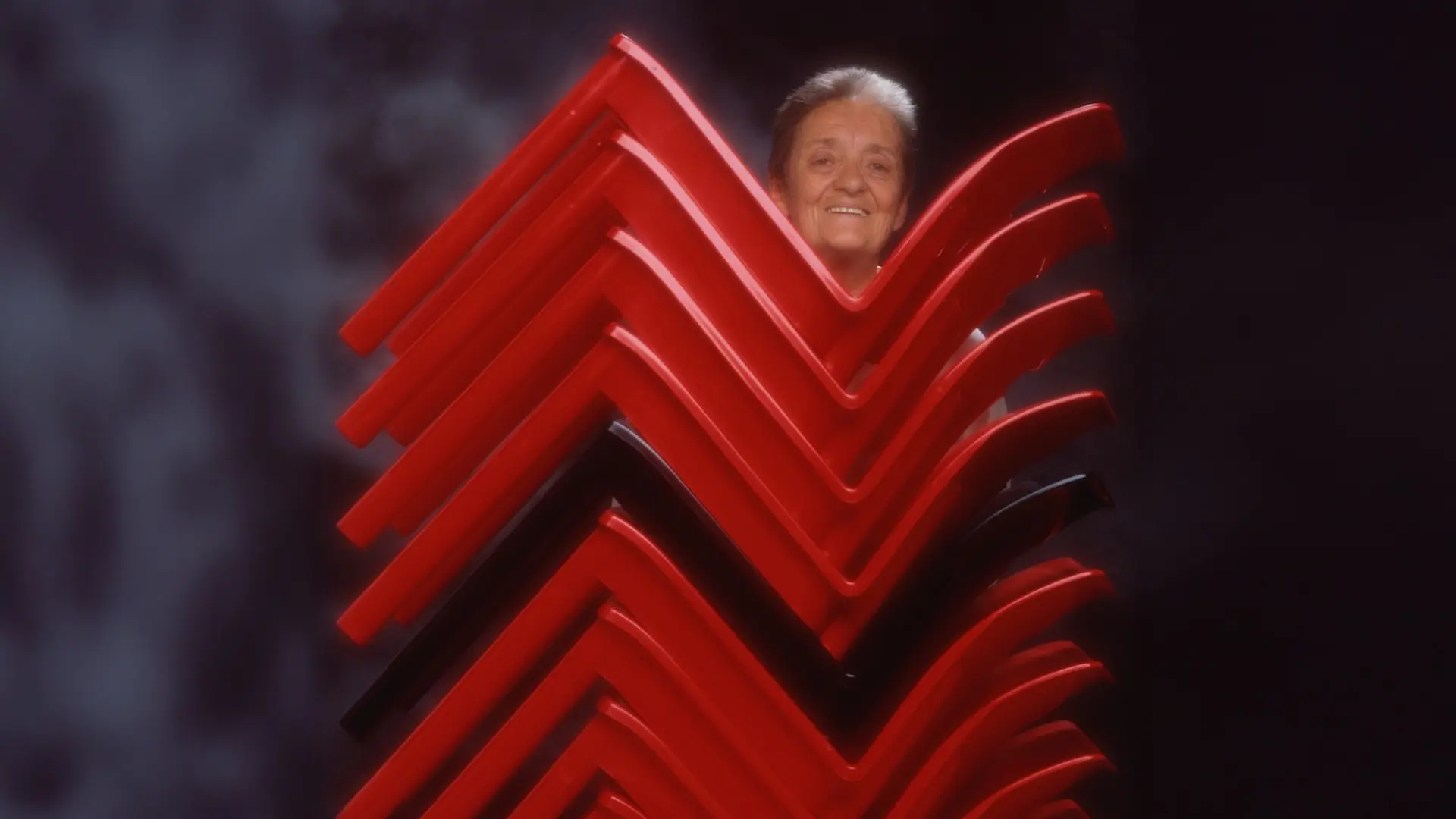

Photo Eirini Vourloumis

We talked with the Cypriot talent about poetry and humanity in design, lighting, technology and sustainability. We also discussed what it means to be a designer today.

There’s something light-hearted and lyrical, yet clear-cut and defined about Michael Anastassiades’s work, both when it comes to lighting and when it comes to furnishing. He has a clear vision of design, which balances form and function and turns the whole experience of creating an object into a sort of reflection on the relationship between the object itself, the context in which it is placed and the person who will use it. Unsurprisingly, his design has been described as an invitation to dialogue, to participation and to interaction. He achieves this through subtraction, a preference for minimalism which, nonetheless, imbues his designs with an evocative power and an unexpected and compelling vitality. Furthermore, for him humanity and poetry have to lie behind the concept. Opposed to disposable design, which caters to passing fashion and taste, for Anastassiades creating means producing permanent value, timeless objects, made to last: this is the highest form of sustainability and honesty that an object can possess.

Cypriot by birth and a Londoner by adoption, he studied civil engineering at London’s Imperial College of Science, Technology and Medicine and then took a master’s degree in industrial design at the Royal College of Art. He set up his studio in 1994, and launched the brand of the same name in 2007. He has enjoyed many prestigious collaborations and many of his works are held in the permanent collections of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Victoria and Albert Museum and the Crafts Council in London, the FRAC Centre in Orléans and the MAK in Vienna.

He practices yoga and meditation, disciplines that may also have influenced his approach to design, which involves exploring new avenues and being open to new ideas, forms and materials. His is always a respectful and holistic approach. We talked to him about poetry and humanity in design, about lighting, smart technology and sustainability. We also discussed what it means to be a designer today.

I started my own brand of lighting in 2007 in order to realise my uncompromised vision of design on an industrial scale. I made a conscious choice to focus on lighting, a medium to which I had always been attracted and which seemed more manageable in production terms because of its scale. In 2011, I was invited by Flos to explore my ideas on an even larger scale and together we embarked on a great journey which is still ongoing. My name became synonymous with lighting. Herman Miller was the first furniture company to invite me on a different sort of collaboration, and I now find myself engaging with design projects of all kinds. My own brand remains my biggest platform of expression.

I spent the early part of my design career questioning the role of objects in our daily lives. I developed a series of experimental pieces exploring the psychological dependency between object and user. My earliest designs were interactive, and most of them incorporated electronics in an attempt to make that bond more obvious. Even though I am now focused on industrially produced objects whose purpose might appear more mundane, the relationship between object and user remains a strong part of this expression.

“Reduction” is a process that I employ that allows me to establish clarity in my personal understanding of objects. I like things to be simple, there is far too much complexity in the world we live in.

I recently had a retrospective in Nicosia, Cyprus, which brought together works carried out over the last twelve years. It came as a surprise to me to realise how difficult it was to establish the chronology through the language of different objects that were occupying the same space.

Currently I have many more opportunities to explore my ideas on a variety of designs and scales. I greatly value all these different invitations.

Your question reminds me of the title of a project I developed in collaboration with Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby in 2004, Design for Fragile Personalities in Anxious Times. It was a proposal for therapeutic objects to help us overcome contemporary anxieties. It is amazing how relevant that project is to the situation we are experiencing today. As a creative I find it impossible to produce objects that are completely independent of the circumstances in which they are designed.

It is important not to alienate people through unnecessary technology, so I try to keep technology “invisible.” As for sustainability, I design things to last for as long as any incorporated technology is able to support it. I value timeless designs as long as they are produced under sustainable conditions.

Beyond our obligation to produce useful objects, our role as creatives is to stimulate the imagination. However now, more than ever, we need to be thoughtful and question whether there’s a need for another object of the same kind.

The Salone del Mobile has always been an important platform for launching new ideas. I am working on multiple projects for my own brand of lighting as well as on other external collaborations. I am also planning an exhibition at the ICA in Milan to coincide with the dates of the trade fair.

Stories

Stories