Everything you need to know about the 64th edition: dates, times, tickets, the return of EuroCucina / FTK – Technology For the Kitchen. And then the International Bathroom Exhibition, and the absolute novelties such as Salone Raritas, Salone Contract and the installation “Aurea, an Architectural Fiction”

The new look of Torre Velasca, in conversation with Paolo Asti

Torre Velasca

Two years on, Milan rediscovers one of its most celebrated icons. Architect Paolo Asti tells us about this challenge and what it means to redevelop a piece of the city’s modern heritage

Eternity, it is said, is the ambition of all architecture. Criticized, loved and hated, nicknamed the “skyscraper with suspenders” by the people of Milan, the Velasca Tower is destined to remain immortal. Designed by the BBPR firm and completed in 1958, the 27-floor reinforced concrete tower featured commercial, office and apartment spaces.

Today’s refurbishment, which by pedestrianizing the entire piazza extends to the urban context, was commissioned from the Asti Architetti firm, working with CEAS and the Milan Archeological, Fine Arts and Landscape Superintendence. The job is part of a regeneration project by development manager Hines, a global real estate investment, development and management company that has invested in the HEVF Milan 1 fund run by Prelios SGR S.p.A.

With a background at Gregotti Associati, in 2004 Paolo Asti opened his architectural practice in the heart of Milan, at 8 Via Sant’Orsola. The firm works on projects that range from residential to office design and retail, focusing predominantly on existing stock through renovation, supplementation and building reuse. Around seventy of Asti’s works are located in and around Milan, from the former Torre Tirrena in Liberty Square to the Banco di Roma in Edison Square and the former Post Office Building in Cordusio Square. Asti implements his designs to revive historic buildings with surgical precision, ensuring that by the time construction is finished, everything looks unchanged, following a measured approach diametrically opposed to showiness. Indeed, Asti has earned the nickname “the gentle architect”.

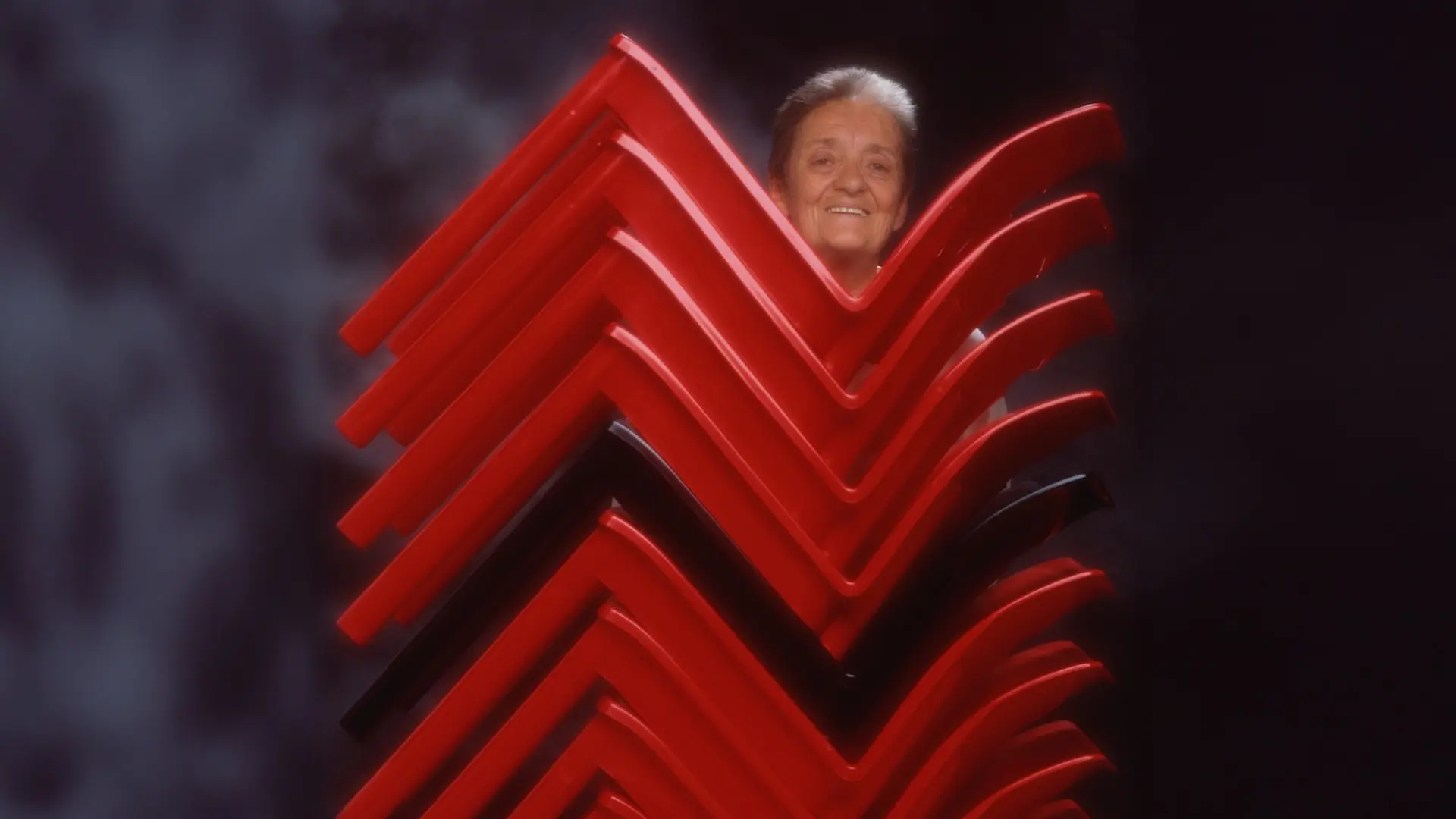

Paolo Asti, photo Andrea Cherchi

After we won the commission, we spent nearly two years drawing up the design. The Tower has been a listed building since 2012: seventy years after it was first built, we worked on restoring its original identity and specificity. Over that time, a great many changes had occurred, especially in the interior.

We conducted material analyses and undertook historical documentary studies, benefitting from access to original architect Belgiojoso’s archives. Perhaps the most critical issue was designing the scaffolding, not least because of the Tower’s particular “mushroom” shape, something that required rather complex static studies. To give you an idea, the scaffolding used 556,000 kg of steel, over 3,000 pipes, 10,000 joints and nearly 20,000 metal platforms.

We are reaching the end of the most delicate phase of the exterior work, the facades, performing structural consolidation and replacing deteriorated plaster with new plaster specially designed with Mapei, a top Italian firm. Working together, we developed a binder to give the plaster the original, iridescent hue it had when it was first built.

Inside, typological and textural restoration work proceeds apace. For the piazza, my hope is to give the city back a space that, looking like a parking lot or some anonymous place of transit, until now has lacked an identity. We want the Tower to have its own churchyard – a secular churchyard for a cathedral to the Modern.

Renovation of the Torre Velasca, photo Albo

Redeveloping buildings and the built fabric is part and parcel of the concept of architecture as living organism. “Bringing buildings back to life” will become increasingly important in future. It is, I believe, a necessity up and down Italy. We must successfully recover our built heritage, which in many cases is objectively obsolete, promoting architectural quality and sustainability while upgrading to cater to modern-day needs. And that’s just the tip of the iceberg for the widespread, item-by-item, building-by-building work leading to a complete metamorphosis of the city. Because Torre Velasca is an expression of Milan’s post-war rebirth, I have felt doubly responsible, even if the job is simply part of a pattern of transforming the “city bit-by-bit,” the approach that has always characterized my work.

My work focuses on recovering a building’s historical presence, and that can sometimes entail demolition and rebuilding anew. Existing buildings weave together an urban fabric that very much needs rebalancing in terms of uses, forms and materials. Today, Milan’s residential buildings fall into two categories: those that can afford to be built from scratch on a more or less vacant lot, and those that stand within the established urban fabric, subject as such to constraints on curtain walling, heights, massing, etc.

Clearly, “free” design makes it possible to fully apply contemporary living paradigms, first and foremost limited land consumption, something that significantly encourages verticality. And clearly, designing upwards frees up ground space that then becomes usable not just for condominium residents but for the whole city. More spaces deducted from construction – and this will become increasingly true – enhance the liveability of the shared areas that form the initial mediation between the city and private space.

Renovation of the Torre Velasca, photo Albo

In addition to several projects in the centre of town, we’re also working on redeveloping large brownfield sites that were formerly landmarks of Milan’s second-tier circle. Two examples for you: the Park Towers under construction in the Crescenzago/Rottole neighbourhood, opposite Lambro Park, and a building on Via Piranesi. These residential projects will attract people to live in and populate urban areas that were once the sole preserve of industry. I am truly passionate about them, because they’ll foster the rebirth of entire neighbourhoods and create alternative hubs. Developments like this are spread evenly across the outskirts of Milan. Indeed, I believe them to be the new frontier of Milanese architecture.

Stories

Stories