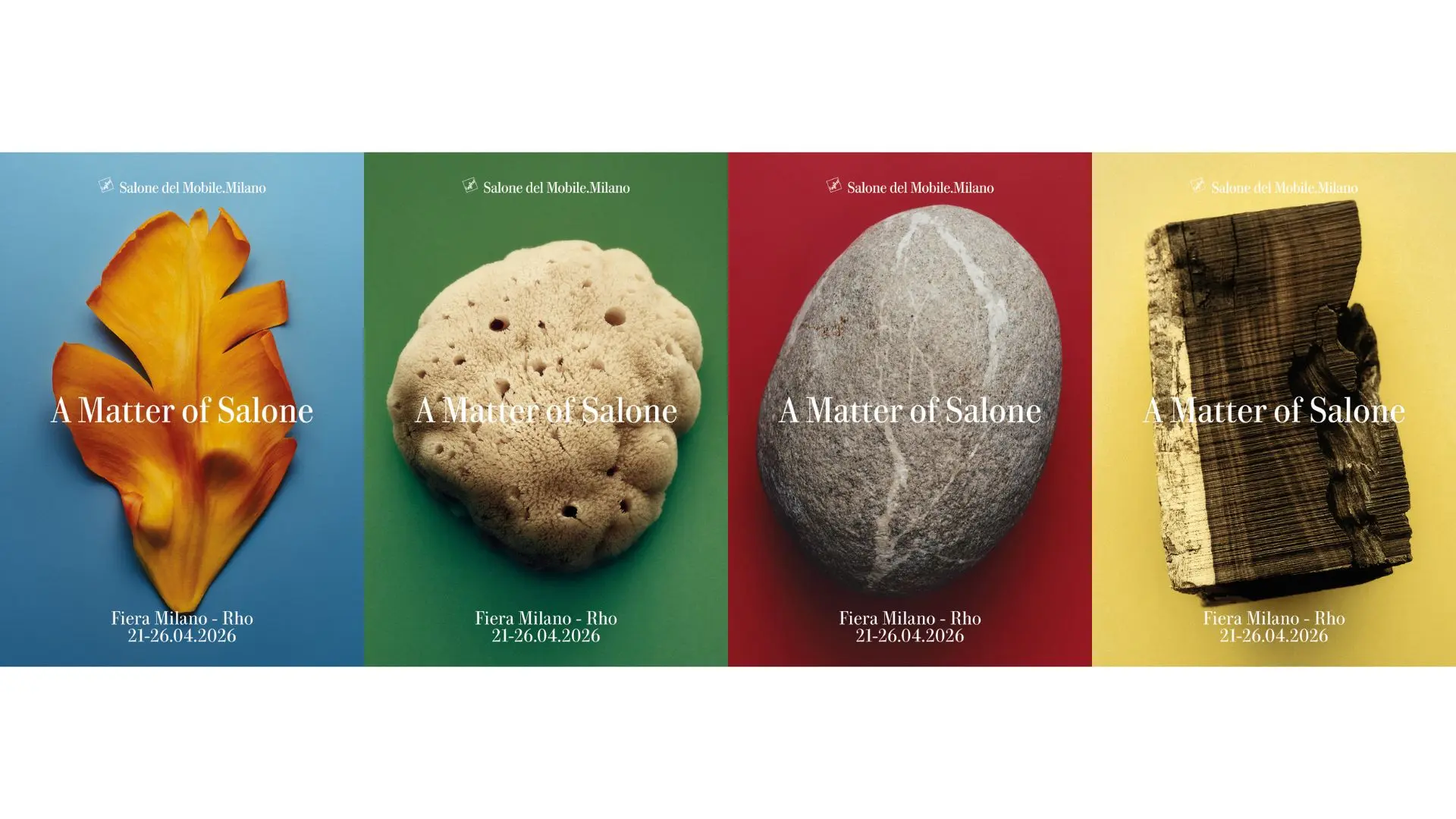

From a reflection on humans to matter as meaning: the new Salone communication campaign explores the physical and symbolic origins of design, a visual narration made up of different perspectives, united by a common idea of transformation and genesis

YOD Design Lab, Buddha Bar, New York, 2021. Photo Andriy Bezuglov

Opened in 2021, the latest brother to the famous Paris venue, this one in New York, has already become one of the city’s hottest venues. Its ingredients for success include an Eastern-inspired design by a Ukrainian design studio, an industrial look and material opulence that relies on the work of an Italian company

Among the various languages it speaks, New York’s new Buddha Bar speaks Italian too. The legendary chain of lounge bars and restaurants, first opened in Paris in 1996 by entrepreneur Raymond Visan and DJ Claude Challe, which today boasts outposts in the world’s major metropolises, last year opened its latest iteration, designed by YOD Design Lab, in the heart of Tribeca.

Developing their concept for a futuristic reinterpretation of the brand’s fusion spirit while at the same time focusing on materiality, architect Vladimir Nepiyvoda and his team chose Brianza, Italy-based company Laurameroni, a specialist in reinventing surfaces through innovative processing.

YOD Design Lab, Buddha Bar, New York, 2021. Photo Andriy Bezuglov

Delving into the Buddha Bar back catalogue, one that has always evoked Eastern influences on its menu and in its interior design and music, the Ukrainian firm put the theme of reincarnation at the centre of its approach. The venue’s colour palette is almost entirely based on dark tones: greys, browns, and deep blues. Some of the building’s original details – cast-iron columns and beams – were preserved, referencing Tribeca’s early-twentieth-century industrial calling before it became a trendy neighbourhood for the jet set.

“We were keen to lend a new vision to a very well-known brand, keeping its DNA intact while inserting it into the overall context of New York,” said Nepiyvoda. “We immersed ourselves in the city’s atmosphere, letting it flow right through us.”

The outsized Buddha at the entrance is not the stereotypical image of the gilded metal deity: it’s a four and a half metre tall parametric sculpture weighing over thirteen tons, made from around a thousand glass slats that reflect light in a special way to make the sculpture look like a giant hologram. Imposing metal chandeliers suspended over the tables in the main room were designed by Kateryna Sokolova (also Ukrainian, born 1984) for the French brand Forestier, resembling drones or spacecraft waiting for permission to land, while still retaining something of the East.

YOD Design Lab, Buddha Bar, New York, 2021. Photo Andriy Bezuglov

As well as supplying all panelling for the project, the Laurameroni company developed a variety of solutions and special finishes for the architects’ bespoke furniture design.

“This was a rather special job for us in a number of ways,” says Matteo Maggioni, marketing and export manager at the Alzate Brianza-based company. “First, it was geographically complex: we’re in Italy, the architecture studio in Ukraine, and the restaurant in the United States, so we had to find a way of triangulating between these three distant places in different time zones. Second, we used finishes more commonly found in high-end residential – brass, fossil woods, marble, metals treated via long and delicate manual processing... – rarely seen in public places, where users are generally less forgiving. The client wanted to invest a lot in this aspect, using high-end materials and lots of detailing to achieve a high-impact atmospheric result.”

For example, the bar counter, one of the focal points in the 850 m2 venue, is decorated with burnished brass metal bands and fitted with custom-made leather elbow rests. The company also designed tall, bespoke consoles with the same upholstery to go with the bar, and a sushi corner custom-furnished with a dramatic Cardoso grey marble counter.

YOD Design Lab, Buddha Bar, New York, 2021. Photo Andriy Bezuglov

From the lobby to the bathrooms, Laurameroni liberally used “liquid metal” - one of its premier, most recognizable finishes – in a variety of settings. Very fine metal powder (bronze, tin, copper or gold depending on requirements and the desired effect) is mixed with solvents to become liquid, sprayed onto a previously prepared wooden surface, and then sanded multiple times.

“Initially, the metal is dull, like when it comes out of the foundry. Then we polish it with increasingly fine papers until we get to the final stage, when we use a polishing machine similar to the ones coachbuilders use,” Maggioni explains. “Requiring long processing times which makes it expensive, this handcrafted process generates interesting contrast effects between shinier and duller areas, creating a sense of depth.”

Stories

Stories