Everything you need to know about the 64th edition: dates, times, tickets, the return of EuroCucina / FTK – Technology For the Kitchen. And then the International Bathroom Exhibition, and the absolute novelties such as Salone Raritas, Salone Contract and the installation “Aurea, an Architectural Fiction”

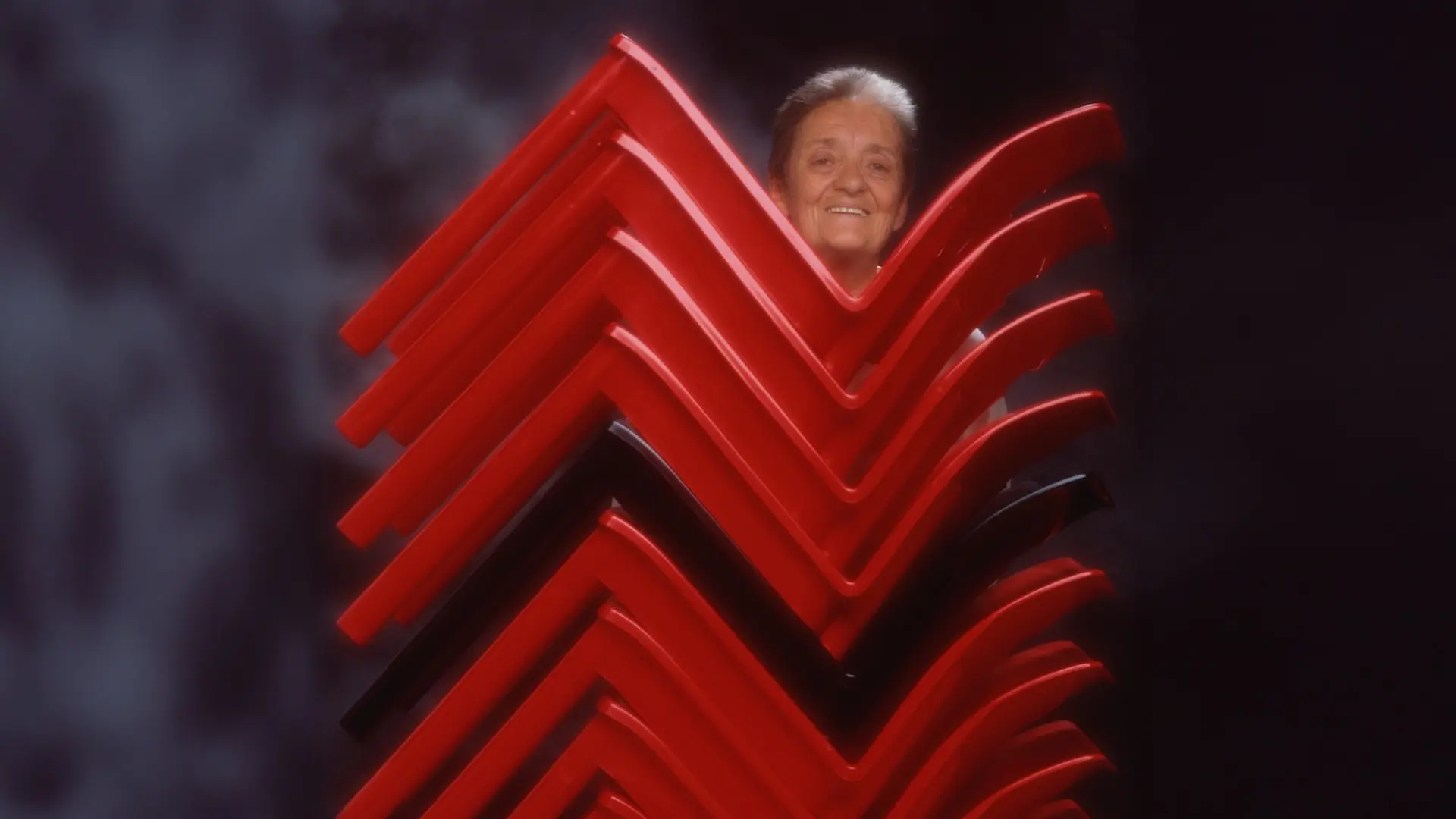

She has restored the dimension of design to a country that had lost it, Lebanon. Since then she has described herself as a local designer with an international outlook.

I’ve known Karen Chekerdjian for many years. Clearly oblivious to her fascination, Karen’s slightly hoarse French betrays a rather anomalous provenance – she was born in Lebanon, a country not particularly famous for its design. Not a “casual” nationality, and one that needs to be flagged up because, although part of her training took place outside her birth country, Karen has always tried (well before the theses about contextual design were propounded) to revisit local characteristics in her work, perhaps in the size of certain pieces, or more specifically in her reprisal of typical techniques or processes. However, nothing was ever interpreted in a folkloristic or citationist vein, with a nod to an easy “Arab-esque” look - on the contrary, a better word would be abstraction. Her work, which really deserves to be better known in Europe, has followed its own, independent pattern, to such a point that it is hard to pinpoint its matrices or to pigeonhole it trendwise.

In our business, being a woman has never been easy and it’s still like that today although the situation seems more evenly balanced. In reality, it’s just a facade. To start believing in yourself again you just need to compare the number of male designers who manage to have pieces in production with the corresponding number of women designers. In any case I have seen that even my own clients are almost always men: that can’t just be mere chance! As regards my decision to go back to Beirut in 2000, exactly a year after Edra produced my first piece, it was certainly a whim, or rather a strong intuition. There was no reasoning behind it: I threw myself into the lion’s mouth with my eyes shut. Perhaps it’s my instinct that always leads me to wherever things are more difficult: I want to better understand what can happen when you put yourself into an unpredictable situation.

It’s not a homage! Just a huge passion for people with the ability to work. I adore the materials and relationships that can be created with artisans. In Beirut there was no furniture industry so I was forced to find another way – I spent a lot of time in workshops trying to work out what could be done and eventually found myself drawn in … but I don’t subscribe to the adoption of great ideas, be they political or social, for merely personal ends – it’s too easy to say “I worked in the region helping artisans develop”, I actually believe these people have given me at least as much as they got from me. I describe myself as a LOCAL designer – it’s something I feel very strongly about. Nothing I’ve made would have seen the light of day had I remained in Milan. So I can say I’m proud of what I’ve achieved at local level. I’m really part of the first generation of post-war designers to have tried to bring back the design dimension into a country that had lost all its creative awareness and ability. That’s why I judge my work very critically within the context of international design.

I feel part of the Milanese school of the late 90s. It’s a realm that belongs to me and I state that loudly and clearly! Everything seemed possible during those years – our projects were just ideas, concepts. We didn’t want to sell anything! In 1998 we wandered around Milan carrying our designs on our backs: everything was thrown open to question. That’s what you had to do and, speaking personally, if I hadn’t done that I would just have produced crap, exactly like many of the things I see today – nobody wants to question things any more, all they want to do is sell, sell any old thing!

That’s the best possible question you could have asked me! Meeting Massimo made me truly discover design, infused me with passion. Even though he didn’t always approve of what I did, Massimo managed to communicate something so true, so authentic that I felt I could do anything - he taught me to believe in myself. Massimo was joie de vivre, bursts of spontaneous laughter, unforgettable evenings and “eating well” – that was his most recent passion – cooking! He used to say, and he was right, “we shouldn’t give a fig about design, what’s important is having fun!” The proof of that lies in the fact that nobody has yet recognised his true value – not a single exhibition, not a single book since he died. If you asked me 100 times who Massimo Morozzi was for me, I could answer you 100 times and then a 100 more in different ways.

You’ve no idea how hard I fought to have my position straddling both art and design accepted. They called me a snob, capable of working only for the elite – 20 years ago industrial design was the only conceivable kind, nothing else! I am effectively part of the first generation to produce artisan pieces in limited editions; a lot of people detested me because that was what I’d chosen to do, but in any case, by going back to Beirut I wouldn’t have had any other opportunities. No industry, and so I was forced to create a parallel world for myself. I still favour handmade and one-off pieces, but by God, in the eyes of the school in Milan I was a heretic!

Precisely. My pieces always enter into a relationship with the space. They themselves are space. I’ve always thought that they had to assert themselves through their mark, leave their imprint on the territory (but without becoming commonplace). I have always designed them in relation to a context and in fact they seem to completely absorb the atmosphere surrounding11 them. I like to think of them as “archaeological” objects – we need to be capable of leaving a trace, and therefore a meaning.

What is Soviet architecture? History, images and pluralism

Amid iconic images and critical reinterpretations, Soviet architecture is unfolding as a set of varied achievements spread across the space and time of the USSR. A journey through contemporary perception, history and case studies to go beyond visual simplifications

Stories

Stories