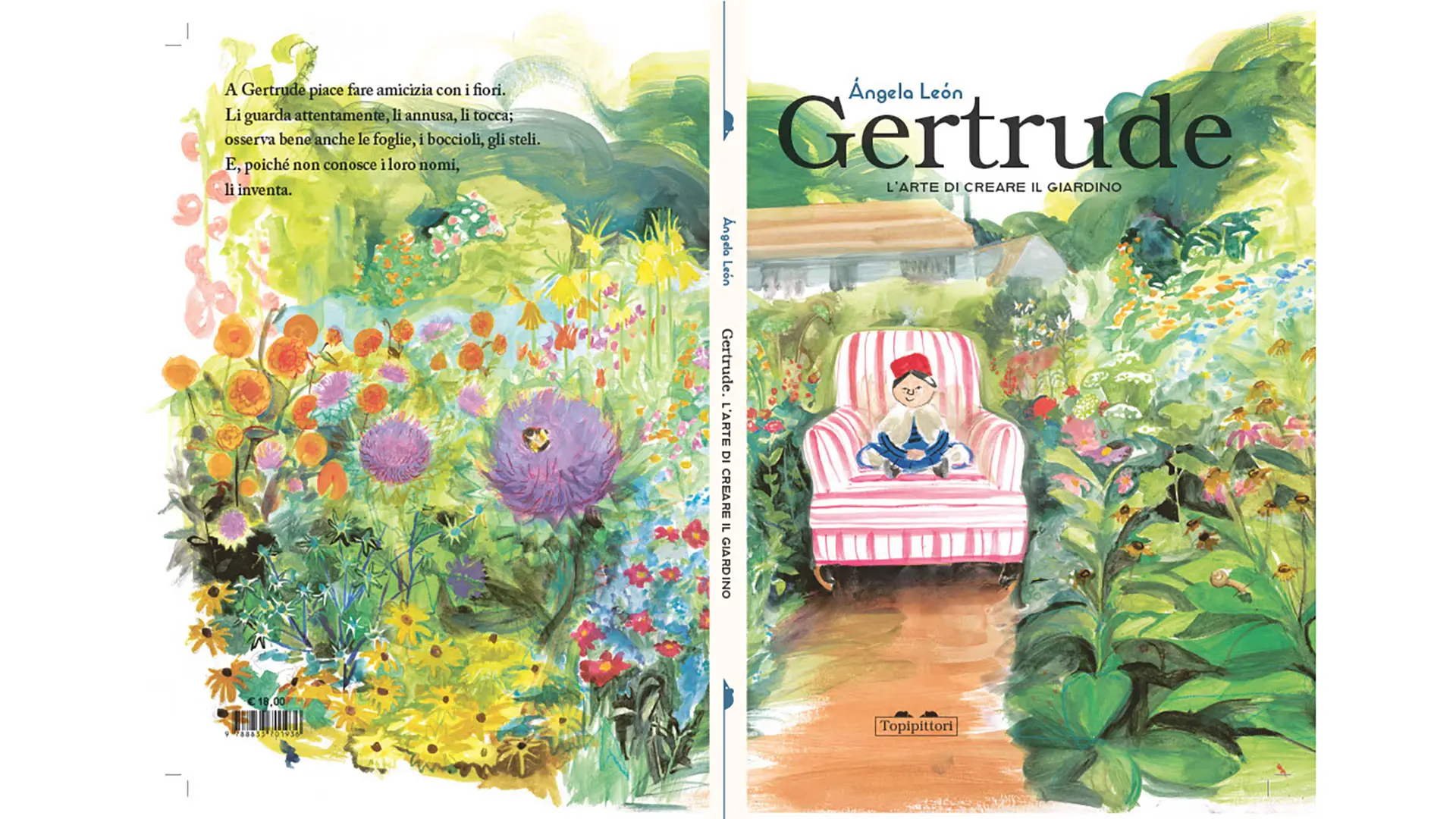

Gertrude. L’arte di creare un Giardino [Gertrude. The Art of Creating a Garden] by Ángela León, published by Topipittori, has just been released. It is the third in a series of books dedicated to extraordinary women who have changed the way we live and inhabit

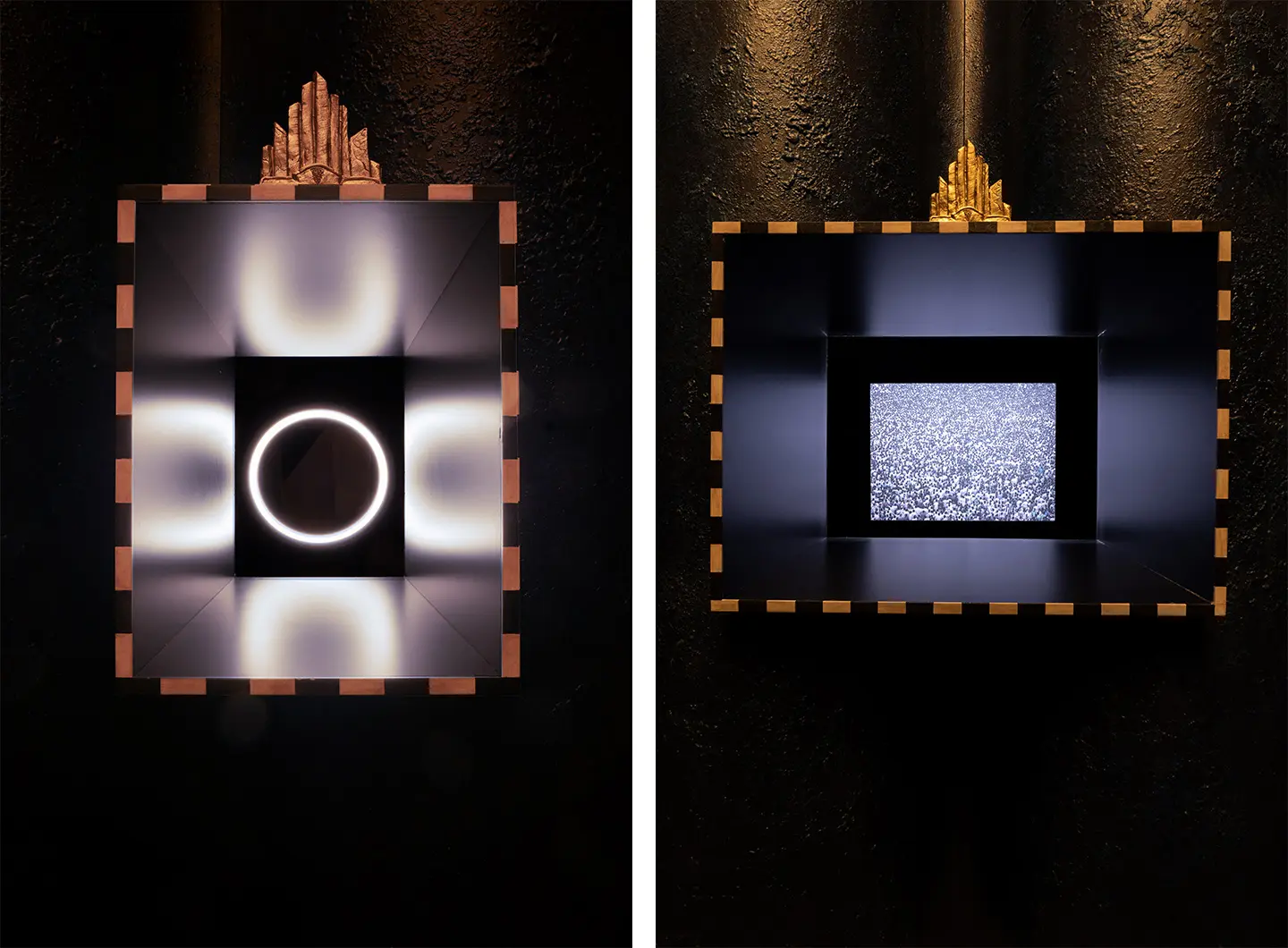

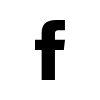

Here are the “Thinking Rooms”, twin rooms designed by the famous filmmaker and set up with the curatorship of Antonio Monda, an ideal prologue and introduction to the Salone del Mobile.Milano 2024

The curator Antonio Monda warned us before the rooms physically existed: “It’s going to be a surprise.” At the entrance to Pavilions 5-7 and, ideally, at the start of the visit to the whole exhibition area, visitors will encounter two ovoid shells, two circular red velvet curtains recalling the iconic interiors of certain scenes in Blue Velvet or Twin Peaks. Surprise and curiosity are also kindled by the fact that these objects are in the midst of pavilions crowded with stands, whose attraction rests on their transparency, their visibility from outside. Lombardini22, a leading group on the Italian architecture and engineering scene, designed the masterplan of the positioning and the architectural layout of the curvilinear perimeter, which leads to the work by the famous American film director. The twin “zones” have a semi-absolute opacity: it is normal to have to walk around them to understand exactly what they are and to find the entrance. The traditional theater curtain is essentially a moving frontier. It opens horizontally to reveal the foot of the stage and shows the way is free towards the dimension of representation. The curtain of “Interiors by David Lynch. A Thinking Room” does not open wide. It encloses a precinct that seeks to retain some properties of the sacred. If we wish to access it, we have the task of finding the entrance.

Inside it, bright red turns to total blackness, to that “absolute, impossible, absurd darkness” that David Lynch loves so much to put in his films, starting with Lost Highway, precisely because it is beyond reality, not found in the world of phenomena. Visitors wait to be admitted to the inner sanctum by observing the photographs by Alessandro Saletta and Melania Dalle Grave (DSL Studio) which recount the creative process of the installation and they approach a screen with the loop recording of a Zoom conversation between author and curator. David Lynch, displaying the camp enthusiasm also found in his brilliant “daily reports”, exclaims: “What a fantastic little room!” And he promises that we will emerge with more energy, happiness and creativity from this room made specially for thinking better. We are in a decompression zone that has a practical function. It controls admissions to this small room that requires a certain degree of meditation, so it cannot get crowded, and at the same time it serves to mark a difference, an environmental break from the rest of the exhibition space, although it is organically part of it, in the same way that the functions of the brain are attuned to all the other functions of the body.

“Thinking not Meditation” the filmmaker is careful to state, despite his well-known devotion to transcendental meditation. In fact, one of the most famous aphorisms in the script of Twin Peaks comes to mind, “I get my news from the only reliable source, cryptic symbolism in my dreams”. The Lynchian dreamworld has the singular and identifying characteristic of being unprocessed, an outcropping of the unconscious that rejects the psychoanalytic order and even exact translation into language. According to Lynch, the images – scenes and atmospheres as well as settings and their furnishings - resemble Rorschach tests that bring out deep individual psychic motifs rather than envisioning a correct interpretation. As Antonio Monda writes, “Lynch manages to seduce us by reaffirming that true art does not offer answers but asks questions.” We cross the threshold of the room and notice some strange, unexpected and at the same time familiar images, which can be traced back to the Lynchian imagination. There is a photograph of an industrial complex reminiscent of the locations of Eraserhead. There is the image of a hanging haunch of beef, immediately evoking Francis Bacon, an artist to whose contortions Lynch is deeply indebted. There is an indefinite crowd counterpointed by the relative scarcity of signs of the setting. There are archetypes: a mirror and a clock. We know that the continuous discrepancy between measurable and perceived time is one of the fundamental features of the uncanny peculiar to the American director. And there’s also – and it couldn’t be more Lynchian – a lot of black humor, if the ambiance promised as a pseudo-new-age oasis of serenity presents us, at first glance, with a quartered animal, smoking chimneys and a time display as intrusive as a memento mori. But it is a matter of perspective: the room, like every Lynchian interior - and like its great forerunner, Tarkovsky’s “zone” in Stalker - is made to elicit a different reaction on each of the individual visitors and their momentary states of mind.

The relationship between the director and the Salone del MobileMilano, design and furnishings is also profound for concrete reasons. David Lynch’s many activities include woodworking and making furniture. This is more than a hobby: it’s an integral part of his creative output. However, in the case of “Thinking Room” the furnishings were not made physically by the filmmaker. The final project and set-up was the work of the artists of the Piccolo Teatro di Milano – Teatro d’Europa under his direction. Technical sponsor: Targetti. We notice brass tubes that do not and should not have a function. And a huge wooden chair supplied with paper and crayons on which visitors can sit and draw, ideally expressing themselves in complete freedom, starting from degree zero. To complete this survey of the evocations, the most essential aspect is missing: colors. Four dominants account for everything: red, black, blue and gold. They are Lynchian colors (think of his well-known drapes, the loggia and velvet) but they are also recurrent colors in the works of another visionary genius and chromosymbolist: James Lee Byars. With enigmatic out-of-scale forms, colors that alternately refer to time and its transcendence, the general structure between the theatrical and the circus, it seems that “Thinking Room” is highly endogamous, nurtured by its creator’s imagination, as well as being closely bound up with the American artist’s work.

David Lynch - Ph. Dean Hurley

Exhibitions

Exhibitions