Everything you need to know about the 64th edition: dates, times, tickets, the return of EuroCucina / FTK – Technology For the Kitchen. And then the International Bathroom Exhibition, and the absolute novelties such as Salone Raritas, Salone Contract and the installation “Aurea, an Architectural Fiction”

The influence of domestic utopias in the book Fast Forward

Haus-Rucker-Co Laurids, Zamp and Pinter with Environment Transformern (Flyhead, Viewatomizer and Drizzler) 1968, from the Mind Expander project. Photo Get Winkler.

What remains of the architectural utopias of the Fifties and Sixties? How do they continue to influence the contemporary habitat? A book by Massimiliano Giberti reflects on these questions through an analysis of twelve iconic houses.

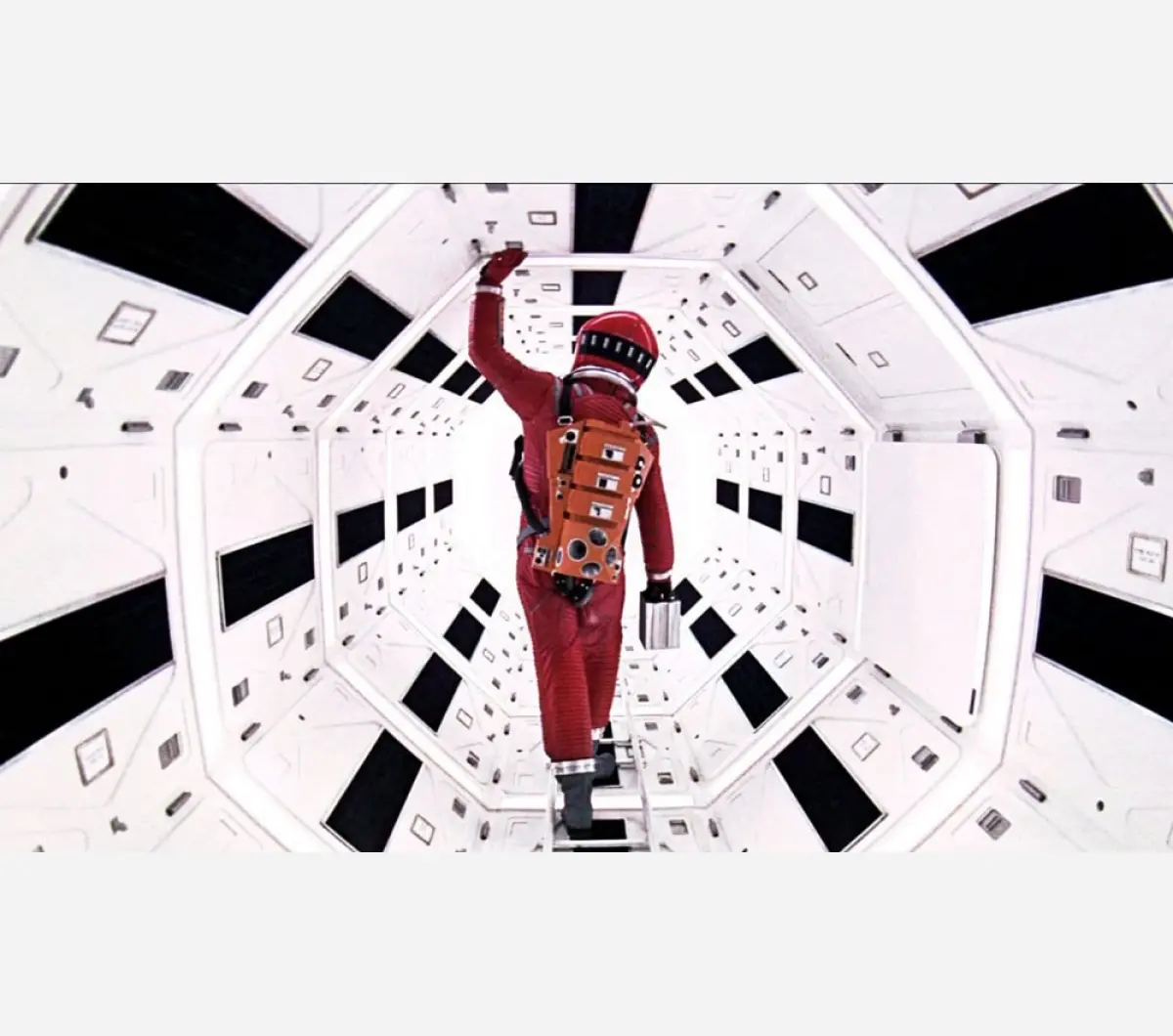

Visitors to the Daily Mail Ideal Home Exhibition at London’s Kensington Olympia in the summer of 1956 were given an opportunity to appreciate how daily life might be in the Home of the Future. The curious habitation/mock-up, in which two pairs of actors moved around simulating banal activities such as ironing or drinking tea, was created by the architects Alison and Peter Smithson in an attempt to illustrate the future of the domestic habitat and, although it was the first to feature flesh and blood characters, it was not the only one of its kind. The Fifties and Sixties witnessed a proliferation of experimental and visionary projects designed to prefigure the world of the future, projecting observers and the few inhabitants - most of the homes were created for demonstration purposes and many of them were only lived in for short periods, if that – thirty or forty years ahead. These homes were conceived like spaceships, with centralised control systems for dealing with any and every practical issue, perhaps reminiscent of the HAL9000 onboard computer in Stanley Kubrick’s 2001 Space Odyssey, complete with futuristic household appliances and furniture in hitherto unseen forms, thanks to the plastic revolution and the new techniques for processing more traditional materials such as wood and metal. These homes undoubtedly reflected the spirit of the times, the optimism fuelled by the economic boom and the conquest of space, and the desire to live according to new, more fluid rhythms, helping to shape the collective imagination by disseminating models that are still applied today, now that the then-future has become our present

Monsanto House. DisneyLand, California (1957). Ph. credits Ralph Crane/the Life Picture Collection

This temporal shock, the time lag between the future imagined in the past and what has actually come to pass, forms the basis for the book by Massimiliano Giberti, architect and lecturer in Architectural Design at the University of Genoa, which kicks off Sagep Editori’s new de_signs series. In Fast Forward: Dal Futuro al Futuro, a collective endeavour that also contains essays by other authors such as Alessandro Valenti, Laura Arrighi and Chiara Centanaro, Giberti retraces the experiments of the “architect-dreamers” of what is generally known as the space age, in a bid to find out how and to what extent their visions were translated into real life or are reflected in contemporary homes.

The House of the future. Alison and Peter Smithson, London (1956). Photo © Daily Mail

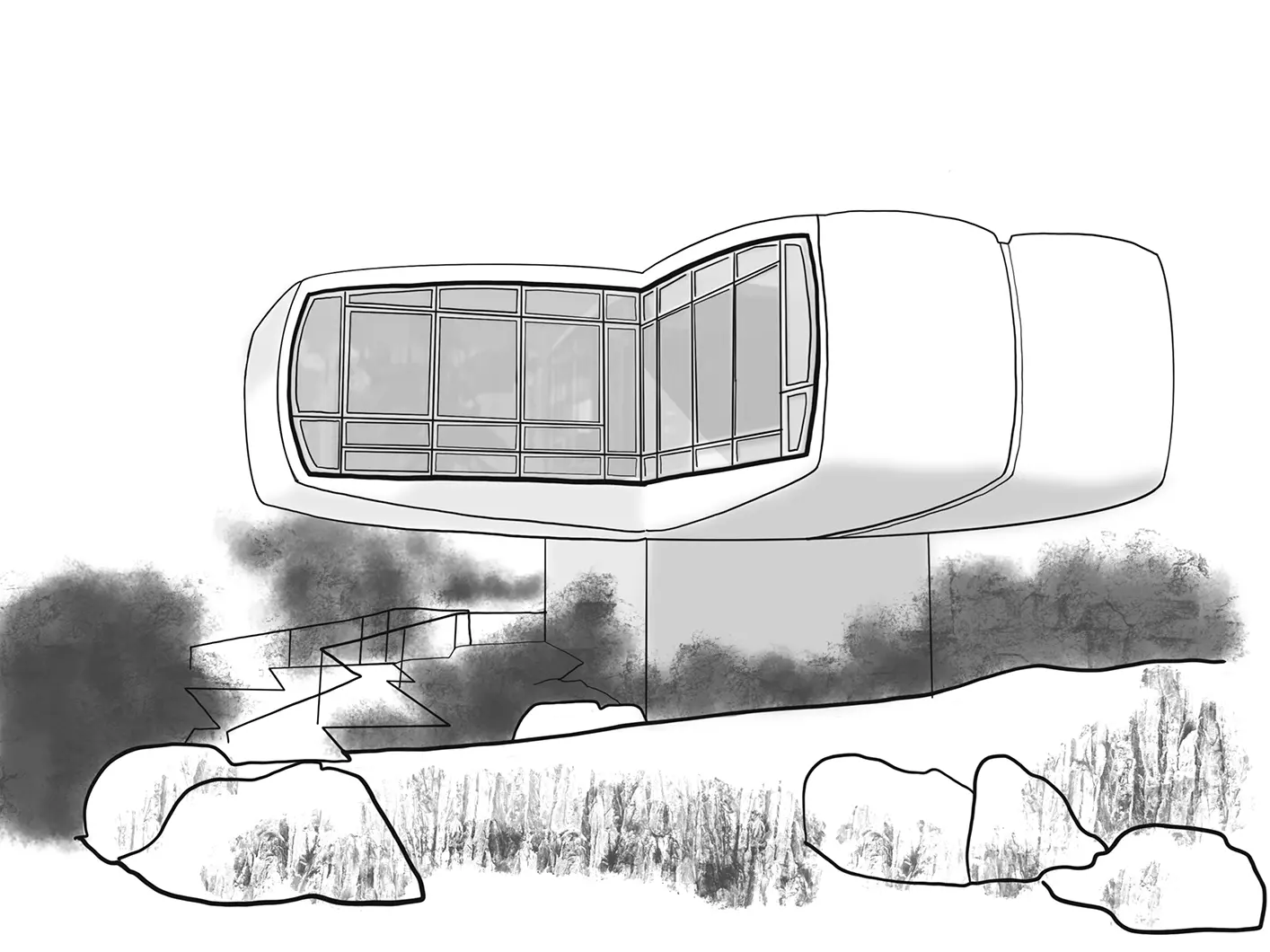

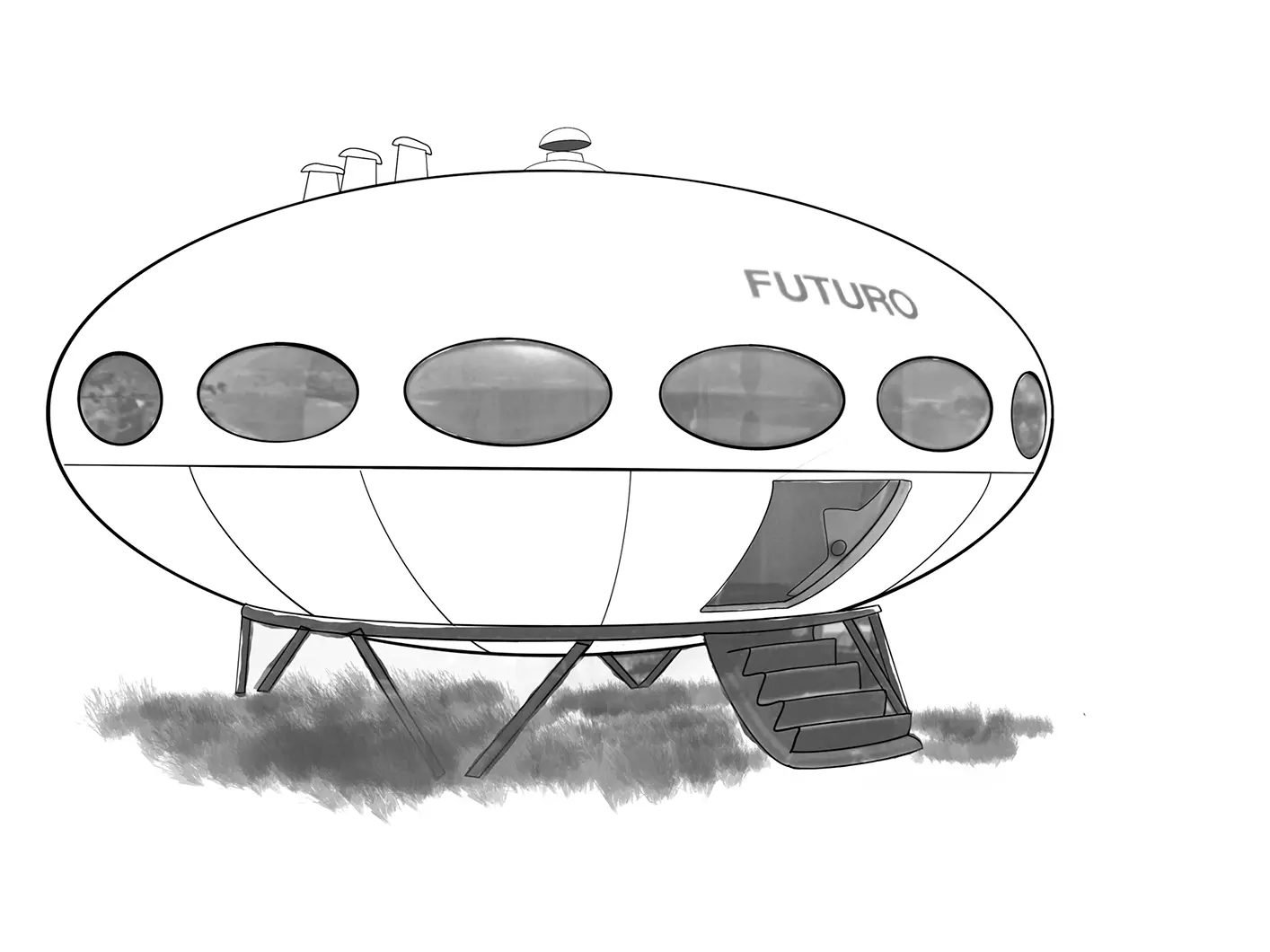

The twelve sample projects, chosen and analysed in depth thanks also to the power of redesign, have seen a range of outcomes – some buildings, such as Wolfgang Feierback’s Kunststroffhaus FG 2000, for instance, are still in use, while others, such as the Monsanto House of the Future commissioned by Walt Disney and designed by the architects Richard Hamilton and Marvin Goody and the engineer Albert G. H. Dietz from MIT, were pulled down after just a decade, whereas others have remained strictly on paper or were part of a wider programme that never saw the light of day. All, though, can be regarded as true “habitable time machines.” “The people who lived in these houses would have been projected into a credible future, because they would have had access to totally cutting-edge technology: electronic devices, cable video phone systems enabling them to communicate with the outside world, kitchens with highly evolved equipment. Some already had microwaves in the early 1940s or early 1950s. There was also a notion of spatiality tied up with a new concept of sociality, with extremely flexible, open spaces that could be shared with other families or used for a variety of other purposes,” says Giberti. While the visionary architects seem to have aced it as regards some of the aspects of life in the future – not all the prophesies came true quite so precisely. Plastic, for example, has slid down the building and furnishing scale since the spotlight was turned onto its environmental impact, while technology, despite being omnipresent, now tends to blend into the domestic space. “The idea of a dashboard or control tower, crammed with switches, lights and buttons that turned the housewife into the captain of a spaceship has gone completely, none of us would want to live like that. With Alexa, Siri and the other voice command systems, we can speak to our homes regardless of where the devices are located. In this sense, the language of the future no longer exists, we live in houses in which there’s no longer a connection between technology and its representation,” Giberti continues. What does resonate with the present, though, and somewhat surprisingly, is the fact that many of these houses were designed to be able to cater for potentially lenthy confinements: “Obviously no-one was thinking about a possible pandemic, but there was the atomic threat and people saw the outside world as potentially dangerous. The thought of self-segregation was fairly widespread, these houses were designed like survival capsules and had to contain everything required to sustain their inhabitants.”

Title: Fast Forward: Dal Futuro al Futuro [From the Future to the Future]. The contemporary home as imagined in the domestic utopias of the Fifties and Sixties.

Author: Massimiliano Giberti

Published by: Sagep Editori, de_signs Series,

Research and Project: Massimiliano Giberti and Alessandro Valenti

Published: 2021

Pages: 148

Stories

Stories