Amid iconic images and critical reinterpretations, Soviet architecture is unfolding as a set of varied achievements spread across the space and time of the USSR. A journey through contemporary perception, history and case studies to go beyond visual simplifications

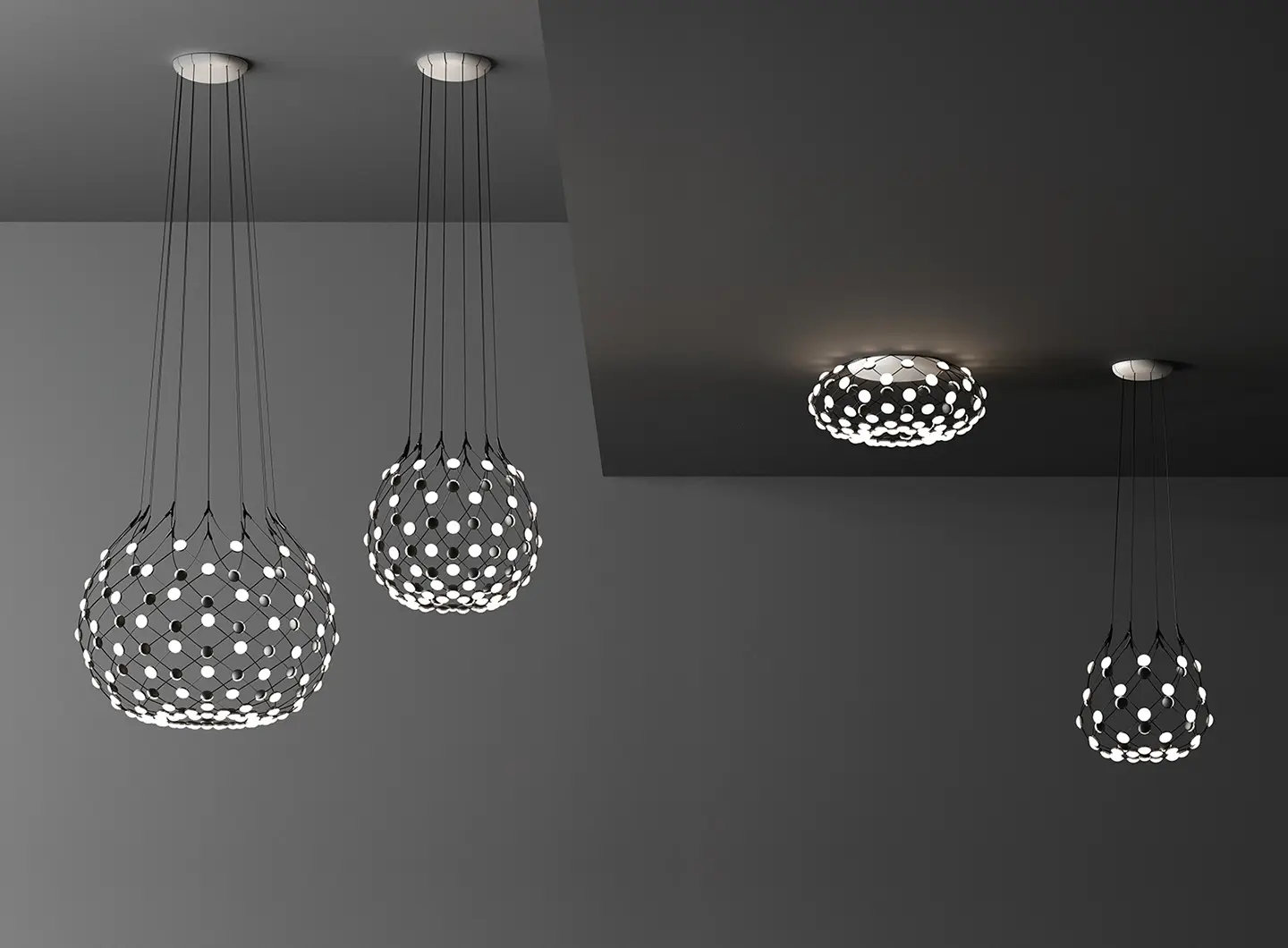

Francisco Gomez Paz, Eutopia, 2018

Contact with materials gives him energy. His hands think and then build. For him, design is an act of cultural expression.

The idea of attributing awareness to contemporary objects, or rather the need to do so, is gaining ever greater ground. What is meant is the ability of these objects to express the reasons why they were produced and the process that has led to their creation. The design principles of Francisco Gomez Paz, and what he does, are a prime example of this. Born in Argentina in 1975, he now divides his time between Milan and Salta, a city 1,200 metres above sea level and 1,400 kilometres from Buenos Aires, equidistant from Chile and Bolivia and a hop and a skip from the Tropic of Capricorn dividing line. Not an easy place to tear oneself away from. Even mentally. In fact, his projects, from the industrial successes – in the lighting world in particular – to the slower and more personal ones, are all inspired by it. It’s where he spends six months a year and has his atelier. Equipped with everything, rather than being a studio in the true sense of the word, it’s a laboratory where the ideas of the Gomez Paz Design & Crafted brand take shape. It was there that the Eutopia chair was patiently crafted, which was acquired by the Vitra Design Museum and won the ADI 2020 Compasso d’Oro award. This was the motivation: “In addition to the product’s design, its design process is also interesting; made in Argentina with simple and renewable natural local materials.”

Unlike Utopia, Eutopia represents a possible ideal. It’s a window of hope for those who live in less structured, unindustrialised environments. I wanted to show young creatives that you don’t have to go and live in great industrial centres to be able to carry out your own projects. That a whole world of new ideas can be born of these contexts, thanks to the opportunities offered by extensive technological knowledge. It was a concept that unleashed so many unexpected things. I took three years to make it, it was my first chair and I approached it with a good deal of respect. I could have gone wrong, but it was a risk that I took upon myself. In fact, I did the work inside my atelier, which I have been finessing for over ten years, and now – partly also thanks to the lockdown period, which made us all endeavour to use the suspended time as well as possible – I can say that it’s now complete, with all the machinery and instruments necessary for creating prototypes and finished objects. Contact with the material is important to me, it energises me. Then the hands do the thinking.

It was one of my first projects, and I owe it to a casual meeting with Andreina Roja, who runs the Sumampa Foundation, which promotes and revives the authentic value of the artisan tradition in northern Argentina. Thanks to her I learnt to see design as a means of cultural expression. It was hugely satisfying to see something made in my own land, using unique technology, that is unknown or not possible in Milan, alongside the best products in the world. I think there’s a mainstream culture, dominant, more effective, but that there are valuable elements in other cultures that cannot be integrated. This could be the role of design: integrating these elements into the system and generating different value, using workers’ know how and artisan techniques which are, precisely, unique. We need to manage to enrich the mainstream, which will always be topical, but not by repeating styles. In other words, I think that the initial perception of an object is linked to its looks, but if you look deeper, it’s the way the project has been handled that brings the true value. My profession can discover all this, if it thinks through its social role.

My introduction to lighting, with Luceplan in particular, just happened. I don’t think of myself as a light designer, I love the holistic mission of design. The broader it gets, the richer it gets. I get hooked on ideas that I convey in the processes and that slowly leads to the shape, to different shapes. Hope opened up an avenue for me. It came just at the right moment, we were studying the application of the new light sources, LED specifically. You could say that Hope is a monument to stubbornness! It was a sign of hope that helped me a lot. Then the company had so much faith in me, following my processes as I continued to try out new avenues, which can sometimes lead to dead ends. I don’t make that many things each year, around 130 prototypes. They take time and commitment, and the faith of the companies is crucial.

It’s a project that I hold close to my heart. Not least because I shared it with Alberto Medo, whom I admire greatly and to whom I am grateful for his professional support. The project was literally born of nothing, he was just back from Africa where he saw with his own eyes the serious problems with drought, and the lack of drinking water in particular, and the difficulties with its transport. So we thought about how to incorporate the water purifying process into a bottle. The prizes we’ve been awarded have allowed us to develop the project, but we’re not a company, we’re still researching. However, a project like this shows just how important it is to broaden one’s own design horizons. A small step, something you do, that can really make for giant strides in society. It’s the story of humanity.

I believe in the power of thoughts. Beauty is the end result, it is the sign of hope. Our prosperity led us to believe in ourselves, but we don’t truly realise that we are a cancer for our species. We are only happy the more we get. It seems as though what we already have or what we have achieved, in financial terms and in terms of objects, is never enough. We need to adjust our sights. Progressing only the things that are really beneficial, and having the courage to drop the things that are harmful. It’s not a question of cutting down, rather of not producing more damaging things in a damaging way. There is no alternative. In order to think about the future and enable a future, you need to have hope and design in itself is hope.

The most exclusive spas in the word, for an experience of true rebirth

From Lake Garda to Lake Lucerne, from Antwerp to New York City, all the way to India: looking forward to the International Bathroom Exhibition, we handpicked the best wellness centres around the world where you can recharge and find a new balance between mind and body

Stories

Stories