From Lake Garda to Lake Lucerne, from Antwerp to New York City, all the way to India: looking forward to the International Bathroom Exhibition, we handpicked the best wellness centres around the world where you can recharge and find a new balance between mind and body

With a fresh view on how to approach the design of pieces that may have a long tradition behind them, Mayice (Marta Alonso Yebra & Imanol Calderón Elósegui) is a studio that is always ready to innovate using new technologies and at the same time keeps an eye on the characteristics that connect us with our heritage, therefore with our emotions. Delicate and powerful, their objects have a distinct allure that makes them very present in their poetic way.

Both of us had always been attracted to design, art and beauty since we were very young. In fact, Marta wanted to study fine arts and Imanol wanted to study Design. We began designing and producing our first pieces of furniture around 2014. We were disappointed working in a world of Architecture full of rules yet with very few opportunities for creativity and innovation, during a period of severe crisis where there was a lack of inspiration and vision for good work that would last over time. We therefore, felt a need to work with the materials and see the processes as a form of expression. We soon realised with the first prototypes that the industry was rather inflexible, always demanding large quantities, and you had to produce prototypes with your own hands or through master craftsmen. We like to spend time thinking, reflecting, before taking action. Prototype until we achieve the best possible solution. We believe that an architect should work the same way as a designer. The big difference is scale. As an architect, you are mainly taught to think and solve problems in different scales—from urban planning, designing a room or even solving a complex structure. This way of thinking makes it easy to shift to a smaller scale, differing in that details take on a greater value and are fundamental in design, where details mean everything.

Sometimes, concepts linked to a story inspire us when constructing forms or using materials. We normally don’t just pick up a pencil and start designing a form, but we look for concepts that inspire us to design. For instance, the concept behind the Filamento design was to create a line of light inside the glass, in an immaterial way. Another example is BUIT for Gandía Blasco, we wanted it to be like a carpet that folds up and builds spaces: a sofa, an armchair. The aluminium mesh is interwoven with textile, a similar idea of how carpets are constructed and is an expression, a gesture that represents the history of the brand. Before designing, we usually spend a lot of time researching the history of the brand or abstract concepts for our designs, in order to help us come up with an idea.

Craftsmanship lets us improvise and build ideas quickly, giving them aesthetic and formal solutions, focusing on the materials, yet always with an imperfect human touch that fills it with beauty. However, technology achieves finishes and processes that are very difficult to achieve in craftsmanship. Combining the two worlds is always very difficult, yet they often intertwine and help each other. Let's say that technology should always adapt to craftsmanship. You should always keep tolerances and variations in mind so that technology and craftsmanship can work together. In the RFC collection of lamps, for example, the aluminium piece had to fit all the blown glass pieces, but glass thicknesses always vary, so the craftsman's skill in adhering to this measure was crucial in this case. Another example: without LED technology and lenses, we couldn’t create Filamento. That's why we believe that craftsmanship can humanise design, because you can see the craftsman's hand with its virtues and defects, and technology helps us enhance and magnify human work.

It was our first commission as designers. We decided to use their collection of moulds, which tallied over 4,000 units, so there was no need to create new shapes. Under closer examination, we found smaller shapes of less than 30 cm in diameter, representing argand lamps, jugs, cups, etc. We then began combining and cutting them after the blowing, tempering and cooling processes, seeking compositions and shapes that did not resemble their original use. Unlike Murano, which places more emphasis on colour, Real Fabrica's glass is characterised by its transparency. When working with glass and transparency, the most important thing is the light source. We bought 25 different bulbs at the market but none of them worked, they spoiled the glass and you could only see the light. It then occurred to us to use some spotlights that we used in an exhibition we held in Villa Necchi Campliglio, and it worked. We fitted the spotlight inside the piece and noticed how the material was backlit, the light source was not visible and the transparency of the glass took on prominence. This meant that we had to design a unique light source for the fixture. That idea changed the way we would see glass and light in the future. There was also a feeling of magic as this light source generated concentric circles on the floor through the glass shapes, as if we were projecting their souls. We went to the glass factory almost every day to work alongside the craftsmen, where we learned how to work and also fall in love with the material.

It’s a magical material. The process becomes hypnotic as soon as you start working with fire. The reed technique has hardly evolved since its inception, enduring over time. The material changes from liquid to solid, varies in colour during the processes and undergoes many processes that make it a sophisticated and delicate material. It is also mysterious. Apparently, there is no scientific evidence or data on when it was discovered in history. One story goes that the Phoenicians, when transporting natron in the Syrian desert one night to warm themselves, used it to make a fire and the high temperatures merged the silica and sand to make glass. This material takes time to learn and understand. You can't just make any drawing, since the technique affects the design. And we like that. We are always learning something about the material and the craftsmen who work with it, which helps us take more creative risks.

Filamento sprung from the observation of how light passes through glass. While working for the Real Fabrica, we saw a surprising effect but did not know why it was occurring. After much testing, we discovered that the concave and convex shapes and a specific light source cause the light to reflect, generating an optical effect, a filament of light. We set out examining a sphere, where the light gets lost in the centre, or a circular tube, where there is no effect. We harnessed all these tricks of light to generate the piece. The shape of the glass is not an aesthetic form in this case, but the means to generate this light effect. There is no effect without the shape.

For No Title, we wanted to see a tube of light floating in space, where different reflection effects appear depending on the viewer's perception. This piece arose from conversations with Rossana Orlandi, who always challenged us to make an entirely transparent glass piece without any aluminium. We wanted to take the transparency of the material to the extreme. The technical development is particularly challenging because the outer part is a single piece of glass containing inner ripples that reflect the reflection from the inner glass tube, generating waves of light. Both Filamento and No Title work with reflection and refraction.

It is indeed important, but it emerges counter-intuitively in the work. It happens through the processes of innovation and trial and error, in a search for beauty. We have both always greatly enjoyed art that changes its perception depending on your point of view, or pieces that build atmospheres and change the space, shifting depending where you’re standing, and forging a dialogue between the spectator and the space. Perhaps all this is in our heads, observing, trial and error, ultimately yielding projects such as Filamento or No Title, which address perception, reflection, refraction, light and glass and the dialogue between spectator and space. Both of us have always loved works containing a dialogue with the observer, one that gives you the sense of being part of it and makes you think about how it was made.

Everything we learn during our own design and production processes is ultimately applied to our work with companies and vice versa. LZF was the first to be able to make a collection. Yet at the same time, combining wood, a living thing, with glass was very challenging. With the expertise of LZF and its team, we were able to solve the problems associated with combining a wooden panel inside a glass panel with a light source.

The shapes of our pieces are definitely not minimalist, they are organic, complex. But the way of working, the use of very few materials in each design, the search for connections and joints as clean and apparently simple as possible, perhaps that part seems minimalist to us.

The BUIT project was a great challenge. With the support of Gandía Blasco: Alejandra, Jose, Sergio, Marcos, Álvaro... their support and patience with the innovation, together with Febrik Kvadrat, who contributed a lot to the project in the textile interlaced in the aluminium mesh. It is still very much a handcrafted project. Working with aluminium proved to be very difficult, a job that was made possible thanks to the engineer Paco Navarro and his dedication and patience. The thickness of the aluminium mesh is at the limit to bear the weight of people, and yet it is so light. The manufacturing process is complex, painstaking and requires a skilled aluminium welding master to join all the parts together. The textile was also very complex to work with, as it is a very high quality, tubular woven fabric from Kvadrat, filled with a special quick-drying foam. Sheathing these two materials was complex, and we had Kvadrat's R&D team to help us interweave and join the entire fabric to the aluminium without any extra materials such as buttons or brackets…. This took over two years and involved many people, notwithstanding the material supply problems during COVID and yet it has a lot of strength and personality.

We have been working with the Suzhou Embroidery Museum for the HSIU brand for more than two years now. This is another innovation and experimentation project with silk embroidery. We still haven't been able to go to China, and it was our first long-distance project. We look forward to unveiling it. Two collections are already designed, one with flat silk embroidery, an artistic piece that floats in space and has the same embroidery on both sides, and “juàn” transparencies, the silk base on which it is embroidered. A piece where the master Zheng Ruying Ms Zhang has been working for six months with millenary techniques. For us, this piece speaks of nature and humanity, but also of time. Each hand stitch and time of this master is captured in this piece with great affection and mastery. The other collection for the HSIU Suzhou Silk Embroidery Museum is more difficult and experimental, involving making a suit out of a piece of glass and floating it in space. As you can see, we seem to be obsessed with designs that float in space and have that point of delicacy. Maybe it's in our heads for a reason. Another project we are working on is a glass fitting for Moritz Waldemeyer's fantastic design, Candle light. This year, he introduced a high-quality development of the animated candle flame. We have also worked remotely, and the crystal piece is very simple in hand cut glass by Real Fabrica, a subtlety that creates a circular halo that accompanies the effects of the wonderful electronic candle, allowing us to hold a flame of fire in our hands. Working with Moritz and Nazanin was delightful. Finally, we are working on the lighting project for Café Barbieri in historic Madrid, a café from the early twentieth century where everything is protected, we cannot change anything. So, our work focuses on light, on illuminating the space and using light and colour to enhance the beauty of this place with so much history.

How to change the world of living from an early age, reading

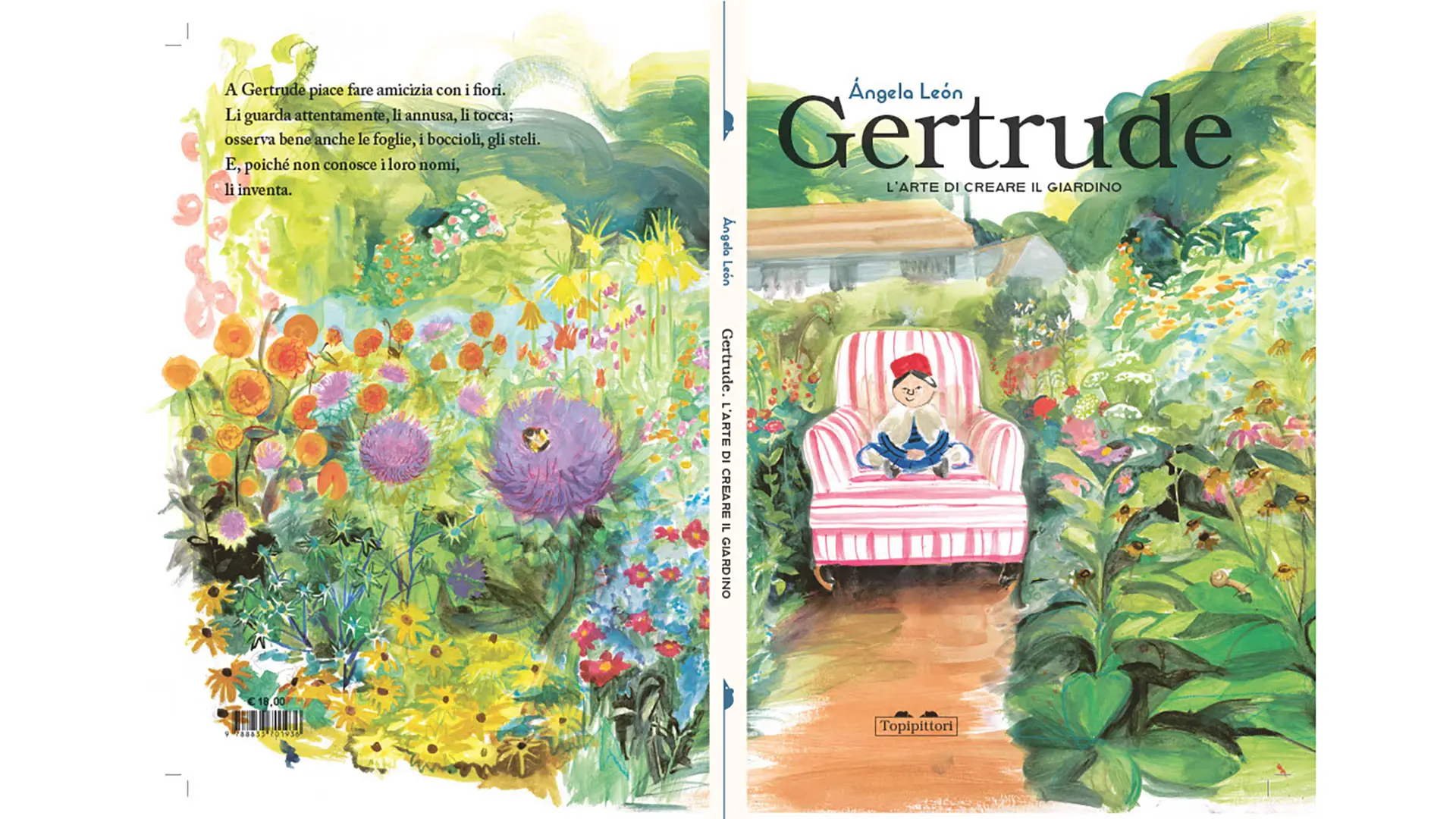

Gertrude. L’arte di creare un Giardino [Gertrude. The Art of Creating a Garden] by Ángela León, published by Topipittori, has just been released. It is the third in a series of books dedicated to extraordinary women who have changed the way we live and inhabit

Stories

Stories