From BIG to David Chipperfield, Frank Gehry to Snøhetta: a world tour of the best buildings set to open in 2026

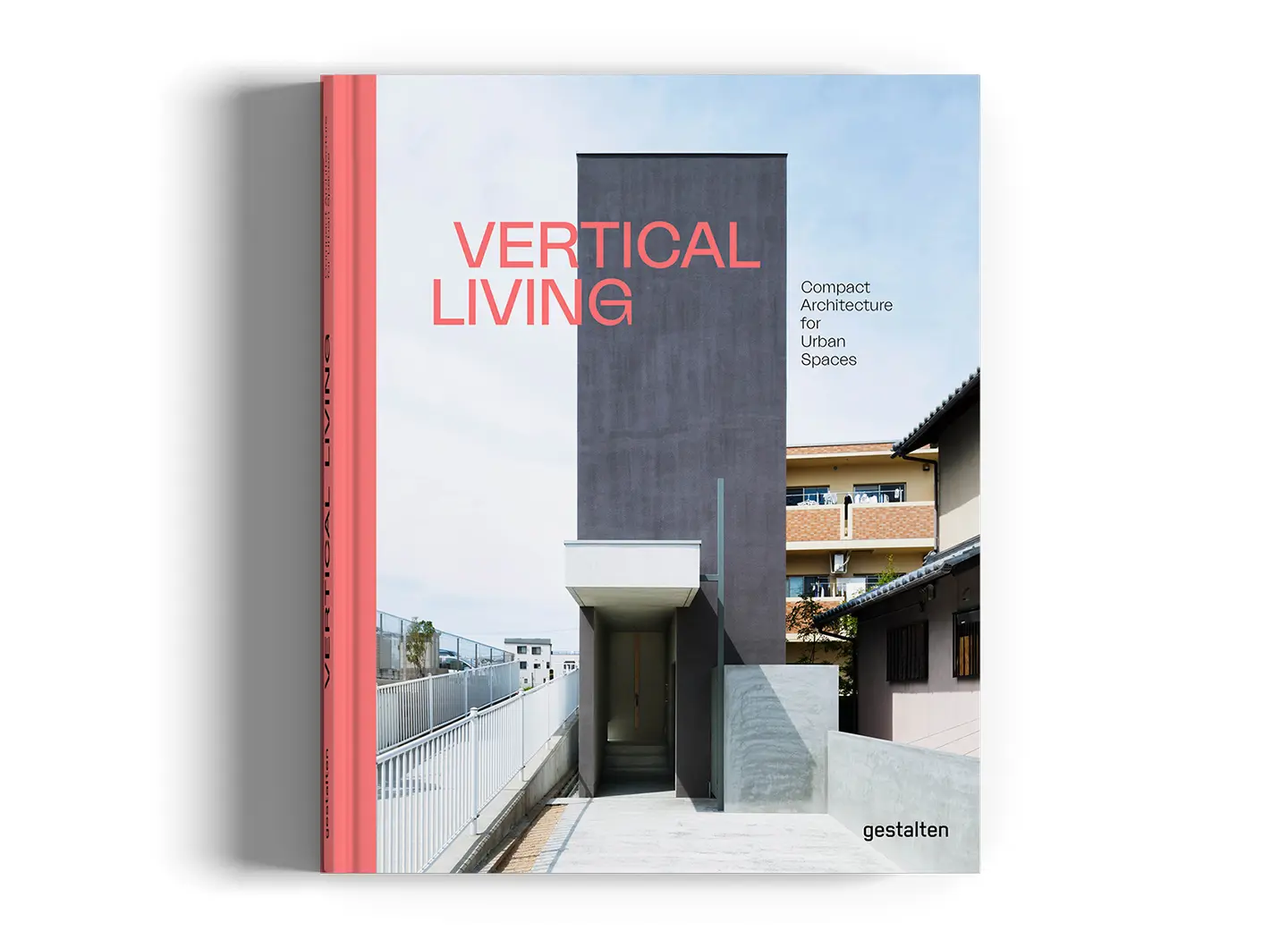

Architects conquer the urban space in the book Vertical Living

Sim Plex Design Studio, Photo by Patrick Lam, Vertical Living, gestalten 2021

The housing crisis in increasingly densely populated cities has led to some surprising solutions, generating new volumes despite the limitations. With an eye to sustainability, what’s more.

An exposition on harnessing space. Urban space, in order to build. Managing to find it is an increasingly arduous task these days. Like a treasure hunt that has made a virtue out of necessity – that of architects who, faced with housing emergencies in increasingly densified cities, have come up with surprising and extremely original solutions that manage to create a feeling of space despite the many constraints.

“Densification asks us to design buildings that uniquely fit a local context,” says Chris Precht, architect and author of the introduction to Vertical Living. Compact Architecture for Urban Spaces. Giving cities back their specific, not standardised character. Without losing sight of sustainability and flexibility. “A sustainable densification is more than efficiency, productivity and technology. Sustainability starts where we, as residents, care about the buildings we live in,” he added. The aim is to be able to identify with our own buildings, which in turn should reference the context, the climate, the local cultures, and be an integral part of a “healthy” neighbourhood. As the author admits, this calls for “ingenuity,” because all cities have to offer these days are small slivers of land. This is where the skill and sensitivity of true metropolitan architects come in.

Oofi Architecture, Photo Nic Granleese, Vertical Living, gestalten 2021

Running to (almost) 300 pages, fresh off the press and containing a wealth of precise descriptive texts and fabulous images, Vertical Living has captured this expertise in an exemplary manner. Starting from the underlying common thread of “maximum impact with minimum space,” we are introduced to rigorously vertical buildings, some more so, some less, slotted into the most unlikely corners, in lots as narrow as fjords or even on top of existing edifices. Always with contemporary comfort uppermost, and often with particular features that conceal internal connection systems, multi-function and space-saving furniture, and windows and stairs of every possible shape and size.

The book opens with elongated volumes, such as the Promenade House, in Shiga, Japan, by Form / Kouichi Kimura Architects with its astonishing dimensions – 2.7 m wide x 27 m long – and the Ch House in Hanoi by Oddo Architects, on five levels boasting vast apertures and stunning voids filled with flights of stairs and a forest of plants. Yoshinori Sakano Architects’ Nami-Nami House in Tokyo has been carved out of a tiny 22 m2 lot, squeezed between other buildings, while the Slim House, one of the many projects by the London-based practice Alma-nac, which specialises in identifying XS lots (this one is only 2.3 m wide), has a gently sloping roof with large skylights that seek out the natural light.

Groupwork, Photo Timothy Soar, Vertical Living, gestalten 2021

Other projects interpret neighbouring architecture in a contemporary key, such as The Coach House by Selencky///Parsons, in London, which slots in between two Victorian buildings setting up a play of architraves and window ledges; then there’s Groupwork’s Barretts Grove with its original typical suburban London brick façade; and Robert Marino Architects’ 5.5-metre-wide East Harlem Housing, its narrow windows duetting with those of classic New York buildings. Backing onto a railway viaduct in South London, the experimental Archway Studios by Undercurrent Architects reinterprets a Dickensian slice of London in Corten steel.

Other examples include co-living solutions that balance considerations around emergency housing, environmental impact and quality of life. The historic Fenix warehouse in Rotterdam has become a mixed-use building thanks to Mei Architects and Planners, and now contains offices, cultural centres, a B&B and personalised lofts, while Precht’s Farmhouse, with its vertical modular habitations, allows each resident to tend to their own gardens, bringing down the environmental impact of the building and contributing to the urban greenery.

The anthology states that there’s no such thing as a “one-size-fits-all solution to urban density,” but that every project – from the 12 m2 hut on top of a building in Quito, to the deconstructed parallelepiped in Tokyo, the triangular house in Melbourne, the micro-apartments in Hong Kong and the building shielded by an almost invisible metal screen in Jakarta – ensures that everything is perfectly tailored to its inhabitants. Alta sed apta mihi.

TITLE: Vertical Living. Compact Architecture for Urban Spaces

INTRODUCTION: Chris Precht

PUBLISHED BY: gestalten

PUBLISHED: 2021

PAGES: 272

LANGUAGE: English

Stories

Stories