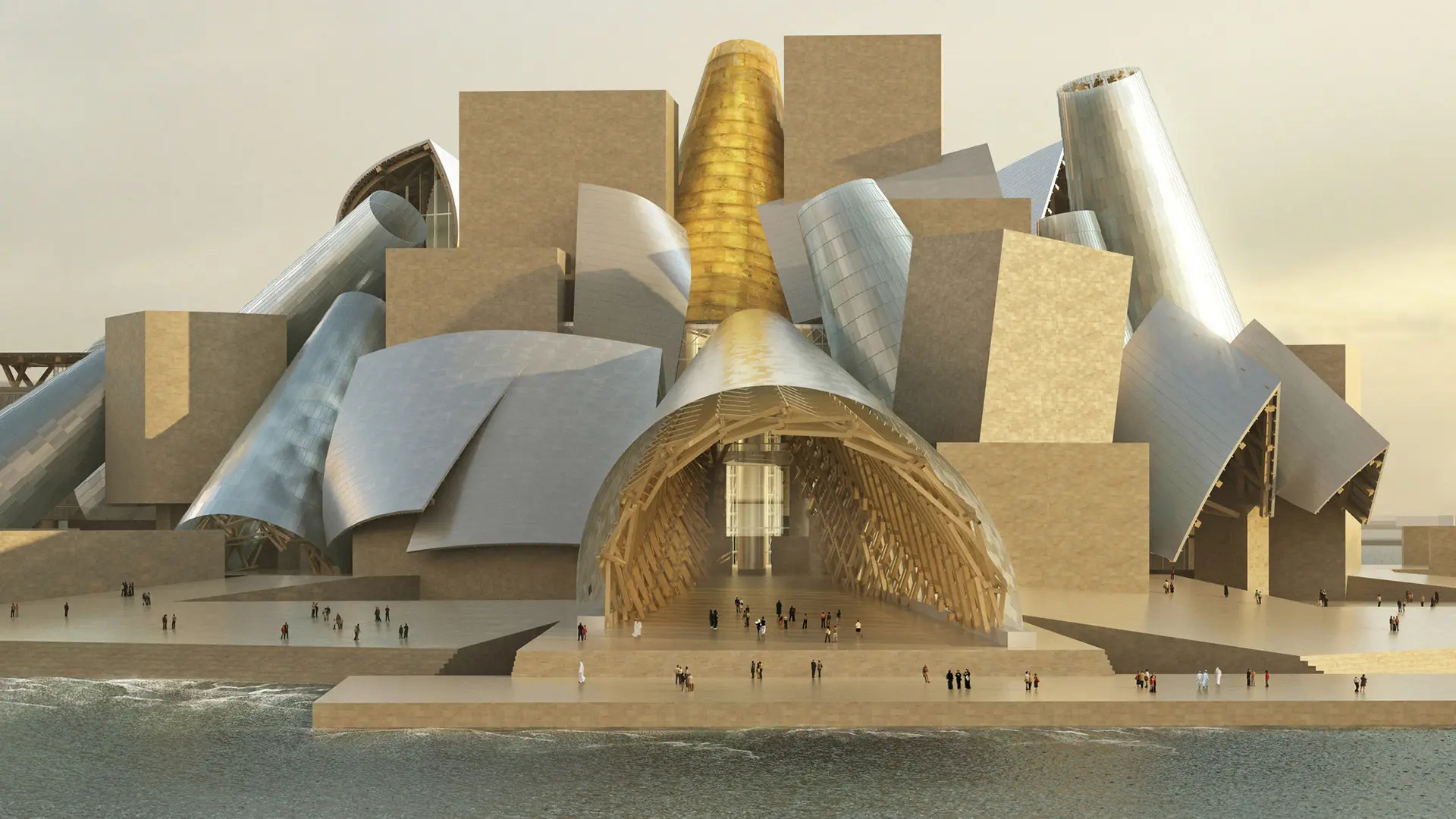

From BIG to David Chipperfield, Frank Gehry to Snøhetta: a world tour of the best buildings set to open in 2026

“A good architect? One who knows how to listen to others.” Ottavio Di Blasi

ODB & Partners, Campus di Architettura Politecnico di Milano, ph. Enrico Cano studio, courtesy Ottavio Di Blasi

The challenge of the millennium for Di Blasi is to make cities more human. This is why he has embarked on a series of “urban mending” projects. Like the recent Architecture Campus for the Polytechnic University of Milan

We’re still on very friendly terms, we understand each other immediately, sometimes all it takes is a phone call to do a project together. We share so many passions and we both think of architecture as a “kit.” We met up again after I left his studio, and I was really pleased. We work well together.

It’s easier to know when you’re dealing with a good architect than with a good project. Because good architects have one instantly identifiable quality: they know how to listen to others, where “others” means not just their own clients and collaborators, but other people generally. The Other. So a good project is nothing more than the result of an exercise in synthesis on many stimuli received in relation to a problem. You could say, therefore, that a good architect is a sort of “organiser,” someone who receives information on extremely varied subjects – symbolic, economic, constructive, social – and manages to give them an overall meaning. A bit like a baker making pastry. When the tart turns out well, it’s a good project.

ODB & Partners, Campus di Architettura Politecnico di Milano, ph. Enrico Cano studio, courtesy Ottavio Di Blasi

It all stemmed from a gift from Renzo Piano to the Polytechnic. As a former student of the university, as I am too for that matter, the Rector asked him what could be done to improve it. Renzo Piano made some sketches that, once framed, the Rector wanted to turn into a real project. I was asked to create it; it opened in June. It can be summarised like this: the Architecture Campus was set up after the war, following Giò Ponti ‘s response to the need for space, which increased by the year, so that in the end it had become a collection of assorted buildings. What we did was to demolish all the secondary structures that impeded the proper use of Giò Ponti’s buildings and build new educational spaces detached from the historic buildings, and plant 130 trees.

When we use the word “campus” we are referring to an Anglo-Saxon typology, in which universities were taken out of cities and into agricultural contexts, constituting a sort of autonomous organism. By contrast, however, in continental Europe, universities developed attached to cities and grew by tapping into their services, which meant the buildings were used exclusively for teaching. The result is that the building density of universities in continental Europe is five times that of American universities. This means that there’s a lack of student space in European universities. That is precisely what we have provided at the Architecture Campus of the University Polytechnic of Milan: we have created more space and added greenery, creating footpaths for everyone and making Città Studi part of the city – the name itself says so. It also encompasses the urbanising role of urban campuses, which is to link into the surrounding parts of the city. It’s a recurring theme in most of our projects in the educational field, such as the UPO Campus – University of Eastern Piedmont, the University of Padua and others still undergoing development.

ODB & Partners, Università del Piemonte Orientale, Novara, ph. Beppe Raso, courtesy Ottavio Di Blasi

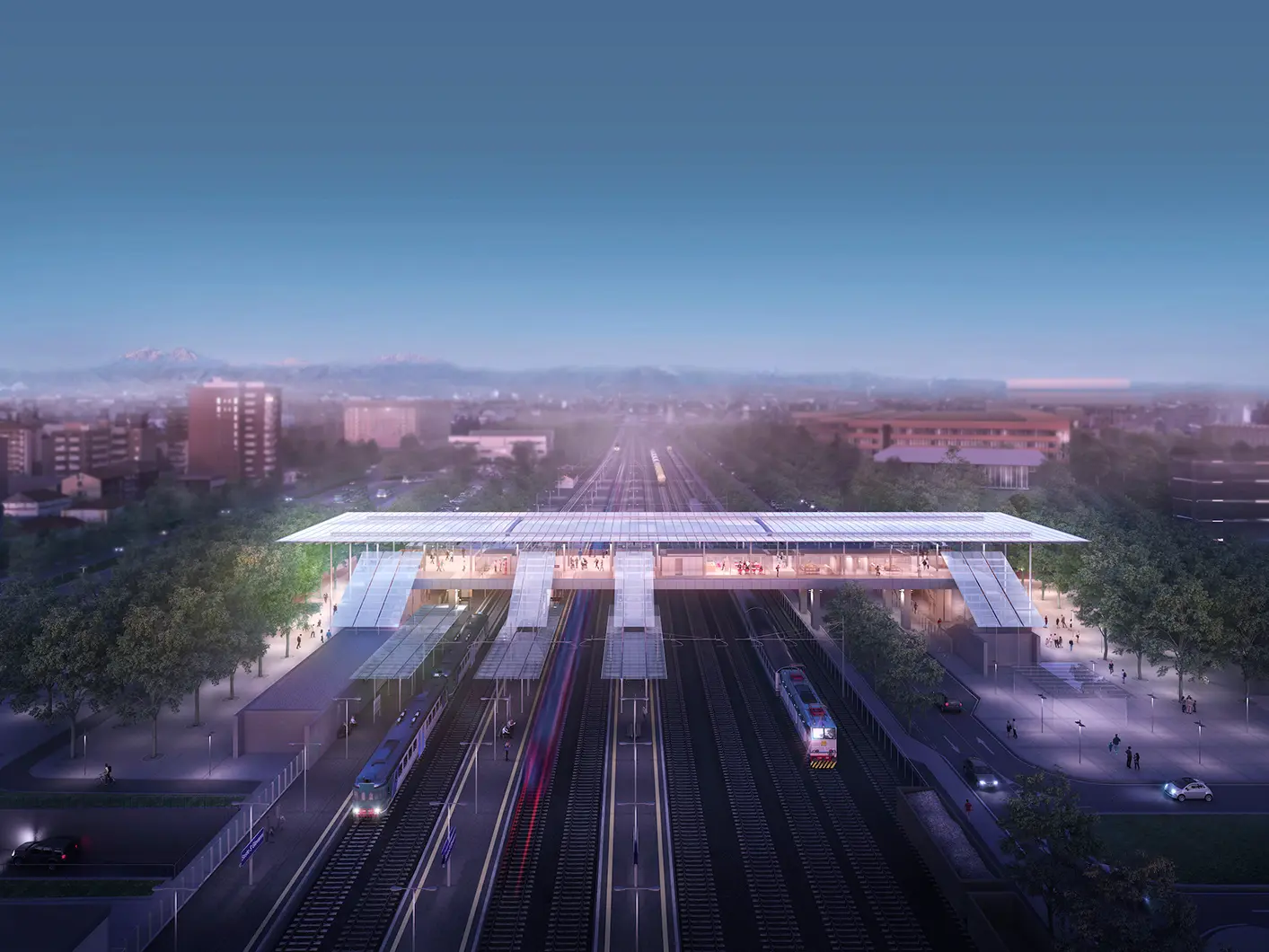

I think Richard Rogers made a great contribution to the question of the future of cities. When he worked for Tony Blair, he put together a document called Towards an Urban Renaissance, in which he identified a number of strategic guidelines that I still regard as pertinent. First of all, cities need to be denser, otherwise they take up more land. This means building on brownfield rather than greenfield sites, something that the most advanced regulatory plans, such as that of Milan, take as read. Denser but better connected, with effective provision of efficient public transport. Lastly, cities shouldn’t simply consume energy, they should also produce it. This is where photovoltaic comes in, it’s the only truly alternative source of energy available to us. For instance, we are working on the station at Sesto San Giovanni, which is a sort of prototype of latest generation railway architecture, because it has 3,500 square metres of photovoltaic roofing.

The suburbs are the cities of tomorrow in a growing urban space. They are often so vast that there isn’t enough economic energy to cope with them all. This means that first of all we need to find out about their specifics, in other words, recognising the vital energies in the area –local markets, youth organisations, social operators – and then identify small but extremely targeted interventions. A sort of “homeopathic” approach, basically, where great results can be achieved with just a small amount of energy. In Giambellino, for example, we took down a wall and created a gate between the local market and the park. Tiny as it was, this intervention managed to trigger virtuous mechanisms for utilising the local area.

One of our current challenges is the Memorial de Gorée, a project for a memorial to the slave trade at Dakar, on the westernmost tip of Africa, put out to tender by UNESCO, that we won more than twenty years ago. We set great store by projects connected with the relationship between cities and universities, such as the project for redesigning the Humanities Campus at the State University of Milan, in the ancient district looking onto Via Celoria. It’s extremely ambitious because it’s not just a matter of making the universities work, but of rehabilitating the cities in which they are located. This is a theme that we will carry forward in the years ahead.

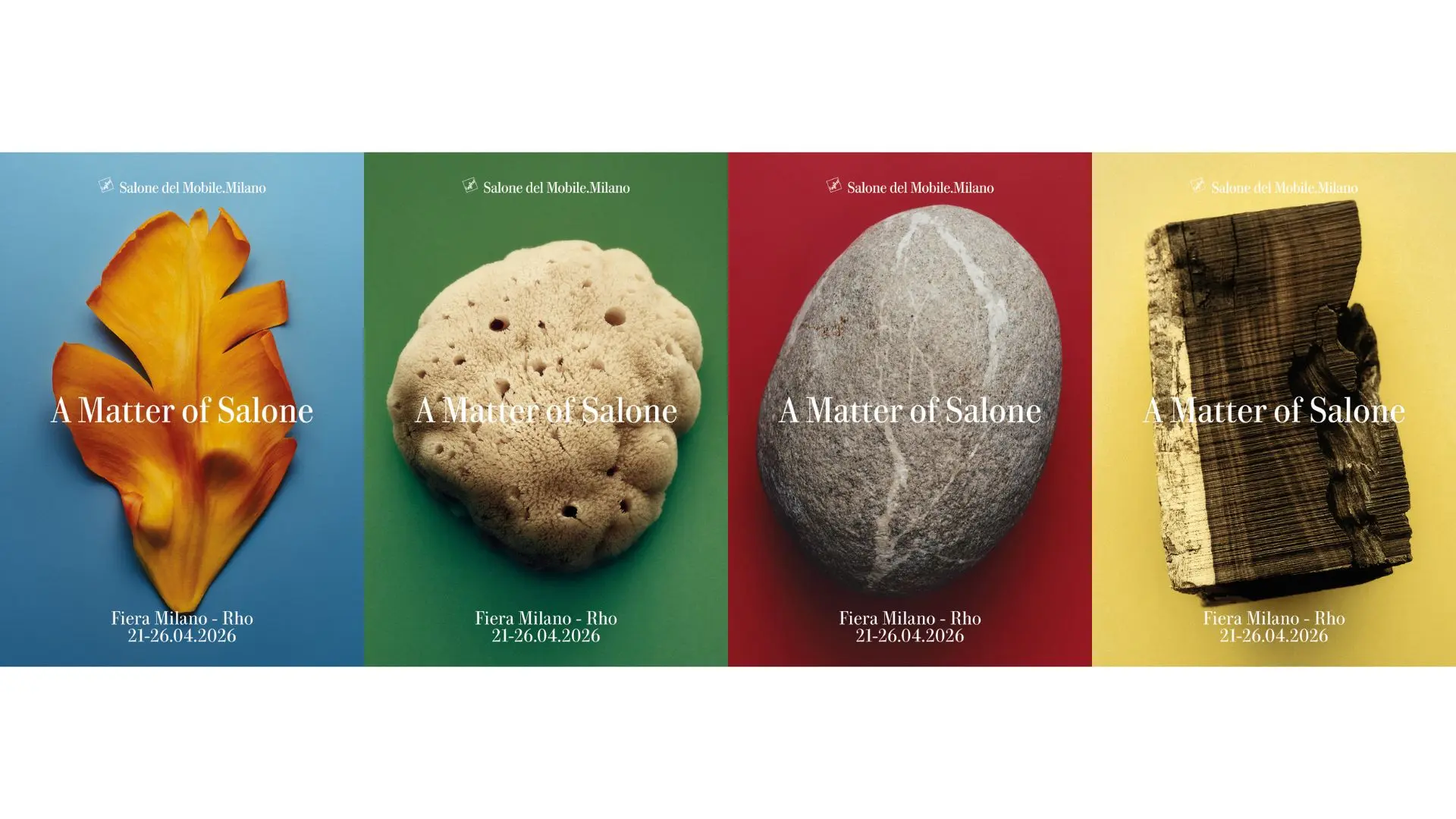

A Matter of Salone: the new Salone communication campaign

From a reflection on humans to matter as meaning: the new Salone communication campaign explores the physical and symbolic origins of design, a visual narration made up of different perspectives, united by a common idea of transformation and genesis

Salone 2025 Report: The Numbers of a Global Event

Data, analyses, and economic, urban, and cultural impacts. The second edition of Salone del Mobile’s “Milan Design (Eco) System” Annual Report takes stock of a unique event and consolidates the fair’s role as the driving force behind Milan as the international capital of design

Stories

Stories