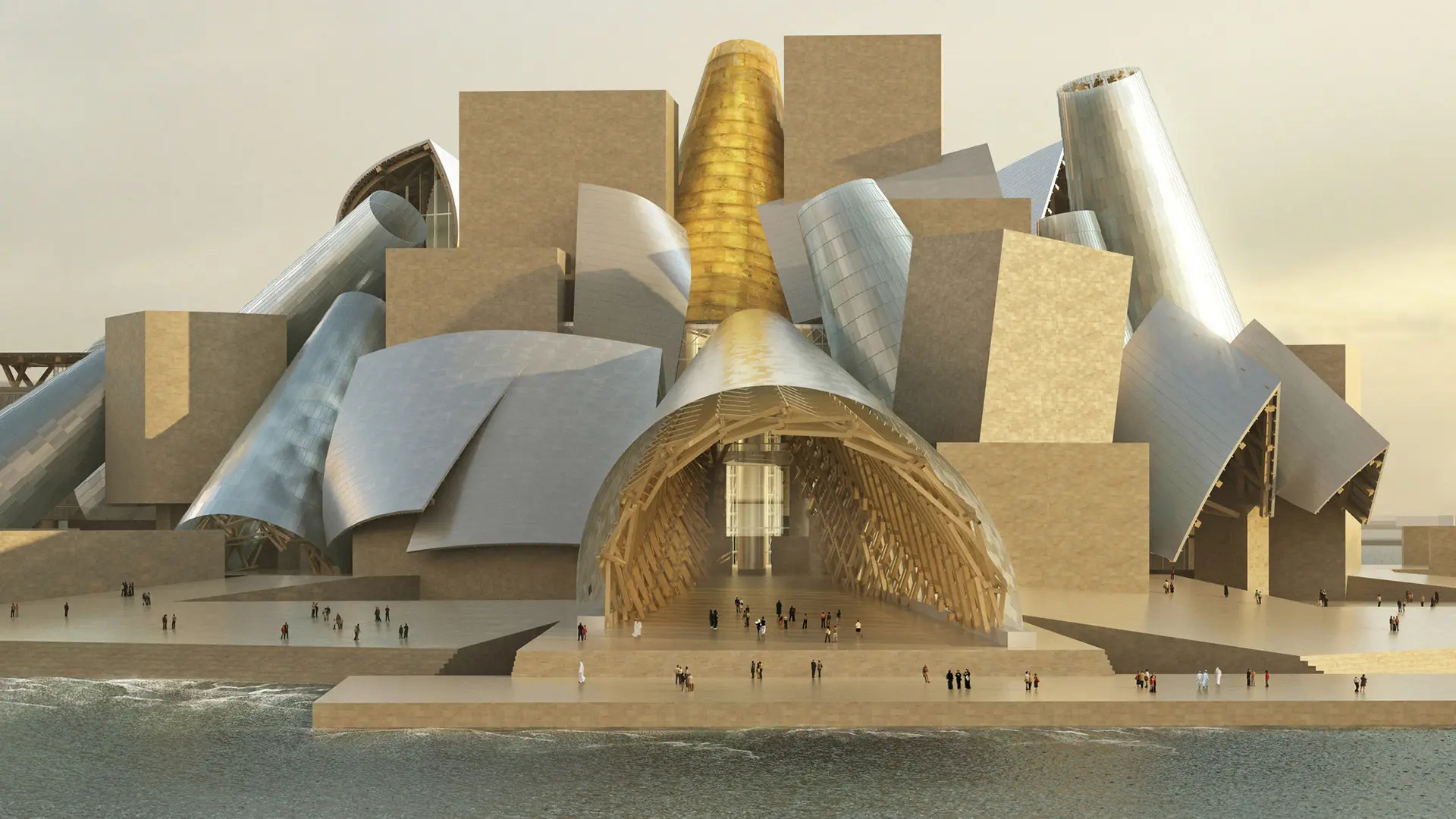

From BIG to David Chipperfield, Frank Gehry to Snøhetta: a world tour of the best buildings set to open in 2026

Nina Bassoli talks about Take Your Seat / Prendi Posizione

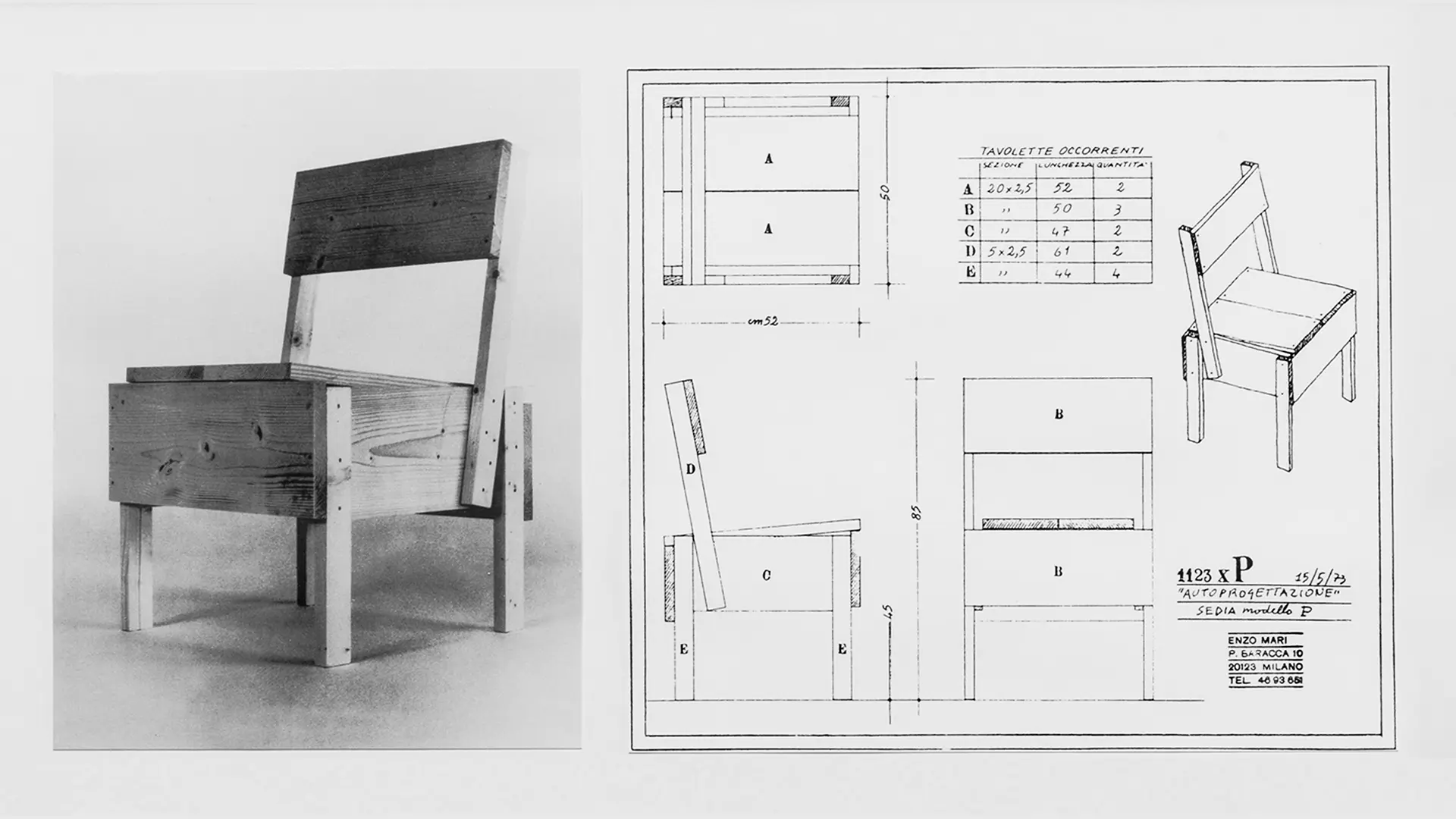

Sedia n.1, Enzo Mari, “Proposta per un’autoprogettazione” ,1974

She’s a Milanese architect and researcher, and the curator of the exhibition being held in collaboration with the ADI - Design Museum at supersalone – and that’s not all

Tell us how the exhibition is structured. How does it play out? Who has put it together?

It’s an honour for the ADI Design Museum to be part of this special edition of the Salone del Mobile, which is clearly an optimistic, rather experimental edition – and so that’s the first interesting thing – the exhibition itself is a bit experimental, a unique exhibition split into four parts between the four pavilions occupied by the Salone plus a small section at the Museum, which serves as a statement of the desire to build a network between the Salone del Mobile and the new city institution, the ADI. In my case, it’s the first time I’ve worked with ADI and I was somewhat surprised and very pleased. I think it’s an interesting initiative even from the point of view of attempting to broaden disciplines, in that as the curator and a trained architect, I am only partially involved with the design world. Alessandro Colombo and Perla Gianni Falvo took care of the installations in the four areas, greatly supported by staff from the ADI Design Museum and the Compasso d’Oro archive, the Historic Collection in particular, which is headed by Alessandra Fontaneto, who acted as something of a Virgil as we navigated this particular “wood.” It was an interesting experience because, although the timeframe was very narrow, we had the opportunity to explore an archive, which is in itself a gift to a curator: the Collection is structured brilliantly, in that there’s a series of objects chosen on the basis of the period in time at which the awards and honourable mentions were assigned, and this is extremely interesting from the point of view of providing an evolutionary history of design, stretching from 1954 to the present day. We decided to work with just one specific type of object in order to try and provide a basso continuo to this chronology, this evolution. We chose the chair, which is in some ways a classic; the underlying concept is seeing what happens over many decades. It’s the first time that not just the chairs that have won the Compasso d’Oro Award but also those that have garnered Honourable Mentions have been exhibited, and so in the end we included more than 170 chairs in the show and in the catalogue (published by Electa). The challenge of the exhibition is to think about this object not just in typological terms but especially in behavioural terms – what does a chair prompt us to do? This was perhaps a choice connected with the strange times we’re living in, in which our changing behaviours are radical and dramatic. The big question at the root of it all is what can design do in the face of these crises and swingeing changes - how does it respond to social and economic change and, in this case, health-related change too? The chair is an excellent item on which to focus these thoughts, in that it’s an individual piece par excellence – I sit on my chair – but it’s also a piece that can be put together with others to form a group. The same is not true for other objects, they don’t have this dual value. The subtitle of the exhibition, Solitude and Conviviality of the Chair, is the thesis. What can we ask of a chair as regards being alone and as regards being with others? It’s a huge topic sparked by reflections on having spent the last few months in great solitude, largely individual solitude or perhaps extended to the family nucleus, but a state of isolation in any case.

Let’s move onto the four (or rather five) sections.

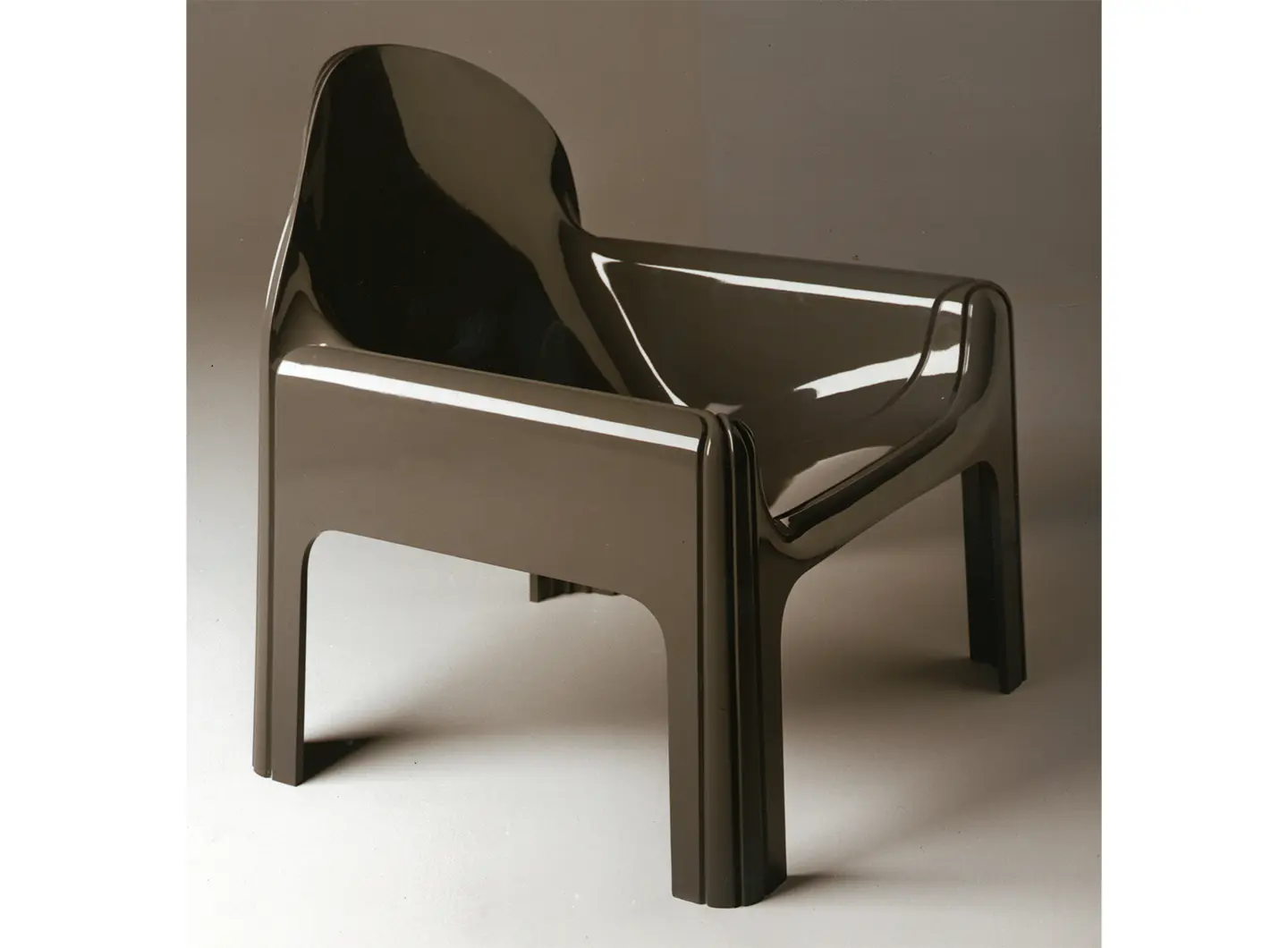

The first section is called Take Your Seat, like the exhibition, and is devoted to what Umberto Eco described as the “secondary function of the chair.” Its primary function is to make you sit in the correct position; its secondary function, however, is representational, in that it conveys a meaning. This section contains the most iconic chairs, the boldest objects from the point of view of their language. They are all single chairs, each arranged on a pedestal, and they are accompanied by a video commentary inspired by research carried by out by Davide Rapp, an artist and filmmaker, and a trained architect and designer, who has created a montage of various film sequences that give a very immediate impression of how chairs have conveyed meanings and to some degree interpreted the different representations of power over the centuries. For example, there’s the beanbag on which poor Paolo Villaggio is invited to sit by his sadistic boss, the Galactic Mega Director. Fracchia (played by Villaggio) doesn’t “know” how to sit on this chair and is humiliated by his “ignorance,” fuelled by his inferior social status. Chairs are, basically, declarations of power in their own right.

The second section, Work Learn Produce, is devoted to the world of work and therefore connected with behaviours around individual learning, working and producing. Naturally the last few months have triggered a lot of reflection, in the sense that all, or virtually all, of us have made radical changes to our working environment. This section naturally includes a certain number of office chairs, but there are also some chaises longues, for example. In fact, also within a modernist concept of industrial design, the chaise longue is a place for free time and in a typological sense, if you like, the complete opposite of office furniture - over the last few months I suspect that we have all sent lots of emails from our sofas or worked for hours on our laptops from our armchairs, and so this sort of more typological or ideological cataloguing of design is becoming more scrambled. The video installation providing the artistic commentary to this section derives from the collaboration between two collectives, Fosbury Architecture and (ab)Normal, who have brought two different research projects together. Fosbury Architecture has been pursuing research into Environments of Resistance for Social Individuals, individual private places (such as St Jerome’s study, for instance) in which one can concentrate, cut off from the world and society while (ab)Normal has been focusing on virtual worlds and on the possible significance of the fact that, when working, one always encounters an interface, which might be a monitor, a screen – or it might be a book or just a blank sheet of paper – that connects one with a different place. Another piece of research has also been added, undertaken especially for the exhibition, which explores the different types of virtual entertainment that have surfaced over the last few months, and have been “introduced” into these private environments, causing a short circuit between the condition of being isolated and one’s relationship with a potential different world.

The third section, Cook Set Share, centres on the times we all eat together, i.e. cooking, setting the table and sharing. It’s probably rather an Italian thing, but there again, Made in Italy remains the protagonist of the Collection. This section is arranged into groups of chairs facing each other, as if they were set out for different banquets. The whole thing rests on the fact that the time we are actually sharing food is only part of the time it takes for the preparations. Designers and cooks often influence each other, perhaps they are the same people who are interested in these two things. A wonderful study has been carried out by Anna Puigjaner, the Spanish architect who set up Maio Architects, on social cooking practices around the world. She talks about cooking not as a private time when the social division of roles means that housewives have to prepare food for their families almost in secret, but as a time for emancipation, sharing and learning – educational, therefore – which happens in various parts of the world these days. The exhibition starts to document a return to sociality, a cathartic moment in the return to sharing.

We then get to the last section, Going out, Going Public, in which the private dimension finally flows into the public space. It’s the liberating freedom of being able to go out, very bound up with current thoughts on what we have witnessed over the last few months: all the bars, restaurants, events, theatres and shows overflowing into the streets in order to adhere to anti-Covid measures. This has been achieved simply by positioning chairs outside. This section contains some very

interesting chairs, because as well as the more classical outdoor chairs designed to live outside, there’s a whole series of folding chairs from all sorts of different eras, often unexpected and amusing objects that demonstrate how chairs can ‘make’ a space. This type of object can be picked up and taken outside from inside and completely change a situation. This section has a commentary by Matilde Cassani who does a lot of work on these themes and whom we invited to reflect on the boundary between indoors and outdoors, which therefore extends to private domestic spaces that can become public, and therefore how this threshold can become increasingly fluid.

These are the four sections at the Salone, one in each pavilion. They are also stand-alone exhibition, but they all make sense together. Then there’s the final section – or the first, if you like – which we’ve called the Fifth quarter precisely because it’s an “extra” section – a small, very precious selection of chairs that are showcased at the ADI Design Museum in Via Bramante. They are chairs that were not awarded the Compasso d’Oro and are examples of more radical experimentation by what one might call anti-system designers, who have taken a rather more alternative path to that of industrial design. It’s also a reflection on how institutions such as ADI - Compasso d’Oro are part of a dynamic cultural world, with which they dialogue and which must never be considered a closed system. Another interesting facet is the rather subtle presence of other arts: a few verses of poetry here and there in the exhibition to accompany visitors and also a soundscape specifically composed for the occasion by the Tempo Reale musical research centre founded by Luciano Berio, which commentates on the four behaviours on a different interpretative level.

Can you name some of the designers featured in the final section at the ADI Design Museum?

For example, there’s the Chair kept for Bruno Mari’s fleeting visits, which remains a mythical object. There’s Michele De Lucchi’s First Chair for Memphis, and Gaetano Pesce’s Golgotha Chair. Then there’s Sedia 1, which was part of Enzo Mari’s “Autoprogettazione” project, which appears not in object form but as a design. It’s also a tribute to a great master who left us not long ago. In the same spirit, there’s one of Alessandro Mendini’s stunning Casabella magazine covers, featuring the chair known as Lassù, which was created for that very purpose and then burnt – a completely useless but sacred object, a “ritual object.”

Lastly, also in the interests of integrated promotion, I wanted to ask you for a few words on the ADI Design Museum. How did it begin? What is it?

For a curator, being able to work with the ADI archive is a bit like a child working in a sweet shop – the manner in which the archive has been structured is affecting, because it follows the chronological order in which the objects were recognised by influential juries, so it has its own very powerful intrinsic spirit, as if it were a warp that can be crossed with different wefts that are selected from time to time. It’s a fantastic museum because it represents such an important cultural institution, so deeply-rooted in the Milan area – and in its economic fabric too, if you like – it’s testament to that crazy time when Italian design really took off and to what has driven it thus far, which has informed this very young institution in the city, a newly-opened museum, which therefore still has to discover its full potential. It’s also a place that’s completely open to the city, in the sense that, physically too, it’s a venue, and has been built as a hub, and so inside there’s a permanent yet constantly changing exhibition, which in turn is enriched by the research and ideas of different curators and designers. In this sense, it constitutes a hub of design, of reflection and of knowledge. Its attraction lies in the fact that it’s very open, very varied, even a bit chaotic, which for me is actually very positive. Now we’ll have to see how it ties in with the other Milanese institutions, strengthening and amplifying its networks, so this exhibition at the Salone would seem to me to be a fantastic opportunity to weave this weft. If I were a foreign or Italian visitor from outside Milan, I’d definitely not pass up the opportunity to visit it right now.

A Matter of Salone: the new Salone communication campaign

From a reflection on humans to matter as meaning: the new Salone communication campaign explores the physical and symbolic origins of design, a visual narration made up of different perspectives, united by a common idea of transformation and genesis

Salone 2025 Report: The Numbers of a Global Event

Data, analyses, and economic, urban, and cultural impacts. The second edition of Salone del Mobile’s “Milan Design (Eco) System” Annual Report takes stock of a unique event and consolidates the fair’s role as the driving force behind Milan as the international capital of design

Exhibitions

Exhibitions