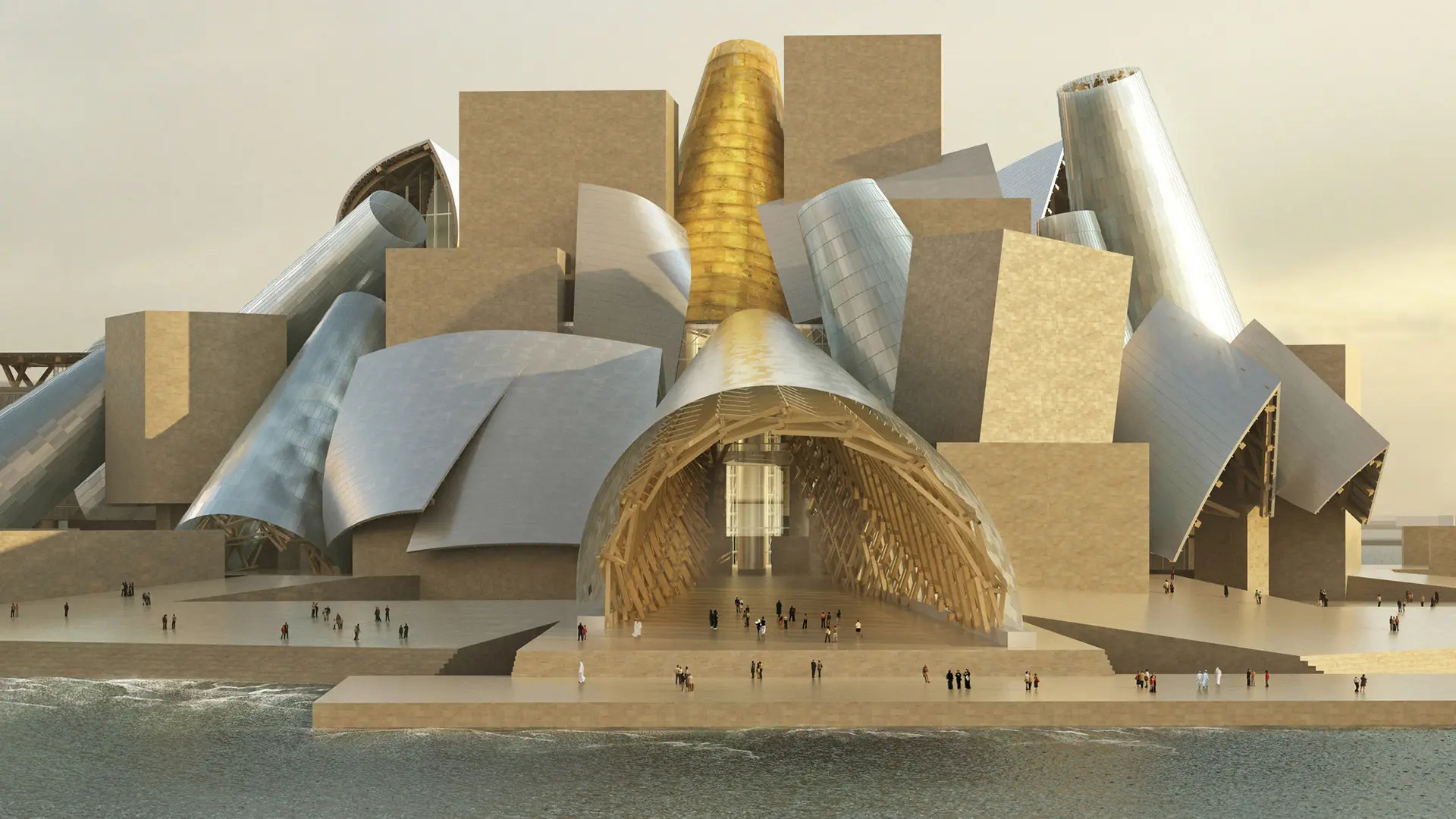

From BIG to David Chipperfield, Frank Gehry to Snøhetta: a world tour of the best buildings set to open in 2026

Displaying is undoubtedly closely related to designing, but picks up powerfully on the concept of setting up. Because, if there is a difference between displays and design, it’s a matter of duration.

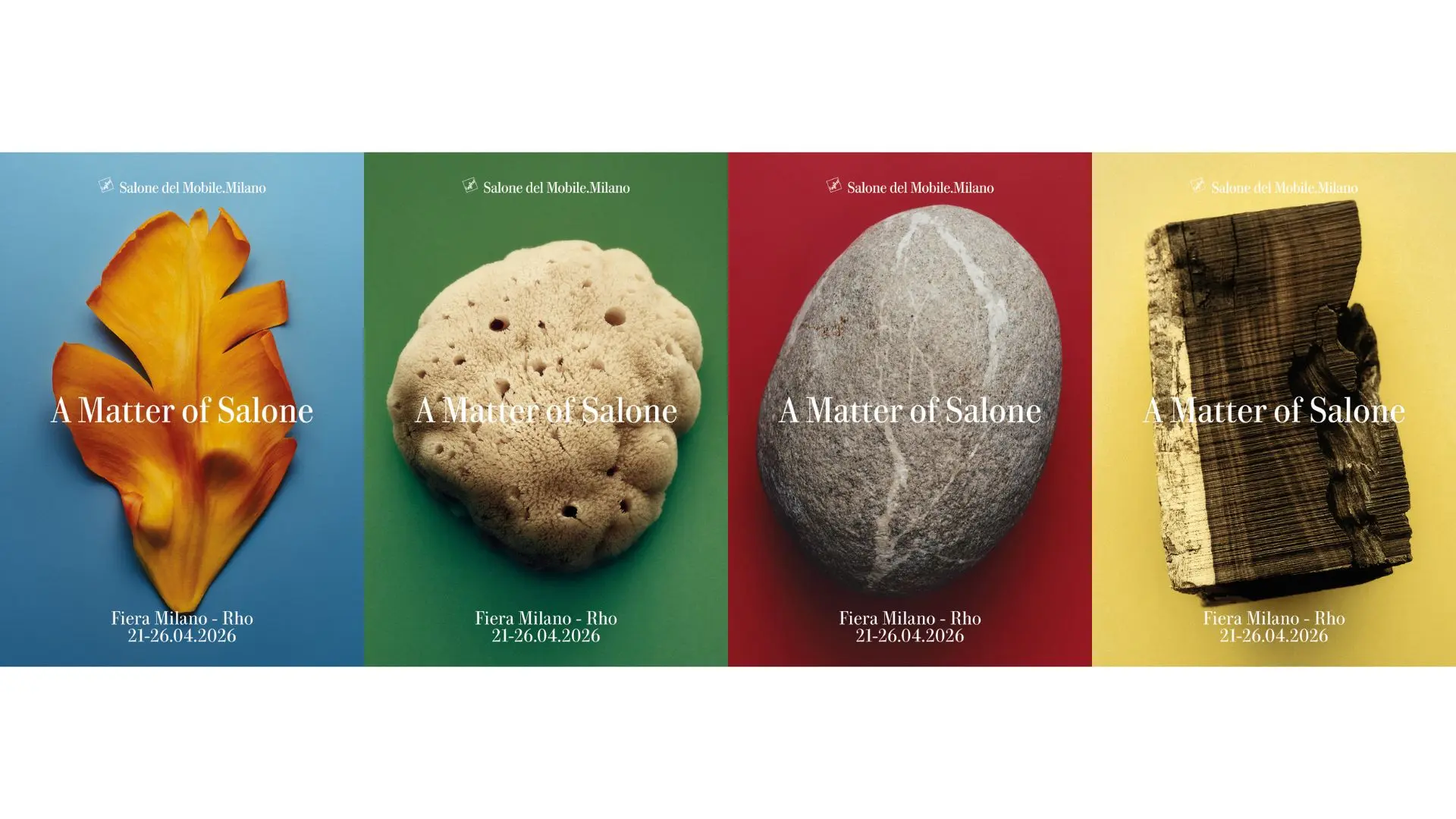

Displaying is undoubtedly closely related to designing, but picks up powerfully on the concept of setting up. Because, if there is a difference between displays and design, it’s a matter of duration. Displays are meant to survive for a short time, from a few hours over supper to a few days on a photographic set, a week on a stand at the Salone del Mobile, or a month in a shop window or art exhibition.

You could say that displays are therefore like concentrated design pills, soluble (rapid release). The effect has to be as immediate as possible. This is where the distinction between displays and museum design (often confused), and the difference between displays and interior architecture (often confused) comes in.

How can you tell if a display has been a success or not? Clearly, a number of questions need to be asked in order to make an informed assessment: “What’s left after the first impression?”, “What levels of legibility/comprehensibility of the works on exhibit have been achieved?”, “How clear is the projected itinerary?”, “What is the synergy between the general mise en scène, the works on exhibit and the graphics and captions?”, “What relationship is there between the duration and the cost of the display itself?”.

According to a formula that has by now lost all meaning by being repeated incessantly no matter what creative activity it is applied to (even making a risotto), we could say that designing a display means “telling a story.” But we must be careful. It hardly ever means our own story (in fact exhibitions staged by the protagonist of the exhibition themselves are few and far between – one could quote Renzo Piano’s impeccable narrations), rather the story of a person, a movement, a material, a company that bears no relation to us and which has to remain the absolute star of the show. The work of an exhibition designer is to “teach [people] how to see.” Teaching them to see the magic and greatness of others. Teaching them to see both the whole and the detail all at once – in this sense, displays are like trees, from far away they are a mass of leaves, from close to you can see every last leaf (as Munari said, trees – and therefore displays – are only there “to make the wind visible.”)

Who were the great display architects in Italian history? Gio Ponti, of course, ever since his 1936 Catholic Press exhibition at the Vatican many years ago, when he turned an access route into a macro-graphic precursor. Franco Albini, naturally, also in 1936, this time in the Antica Oreficeria Italiana goldsmiths’ exhibition at the VI Triennale di Milano, with showcases as minimal as they were precious. The Castiglioni brothers, obviously, during the 50s and 60s, narrating challenging subjects such as fertilisers and plastics for Eni or Montecatini. AG Fronzoni, clearly, capable of combining style and volume to almost achieve a supremely expressive nothingness (remember the impossibility of the Concrete Poetry exhibition at Cà Giustinian, Venice in 1969?).

What about the fairly recent past? Pierluigi Cerri, Italo Lupi, Gianfranco Cavaglià, Umberto Riva, Ferruccio Laviani and various other younger designers (Lorenzo Damiani, Paolo Ulian, Calvi Brambilla, Massimo Curzi, Alessandro Colombo) understood that display, with its rhythm and ceremonial, can be a peerless training ground for design.

What about rules for creating a good display?

Are there any rules for creating a good display? The first is taken for granted, and isn’t really a rule anyway, more a sort of moral law, and that is that one must feel great empathy towards the subject, the person and the themes that are being presented, all the other rules begin with DO NOT, just like the 10 Commandments in the Bible (but at least if we get it wrong, a display will not see us cast into hellfire!).

Do not try to replace the curator (try and learn with them, planning)

Do not prevaricate (underscore instead)

Do not imitate (work by contrast instead)

Do not confuse the user (guide them instead)

Do not take anything for granted (better boring than elusive)

Do not underestimate the power of light (even for an exhibition in the dark!)

Do not underestimate the importance of graphics (better didactic than cryptic)

Do not whisper, but do not shout either (nobody here is deaf!)

Do not assume the public know it all (the designer is the person who can talk to everyone)

And, especially, do not believe you’re God! (which is a problem in most contemporary projects, both in architecture and in design).

Stories

Stories