Everything you need to know about the 64th edition: dates, times, tickets, the return of EuroCucina / FTK – Technology For the Kitchen. And then the International Bathroom Exhibition, and the absolute novelties such as Salone Raritas, Salone Contract and the installation “Aurea, an Architectural Fiction”

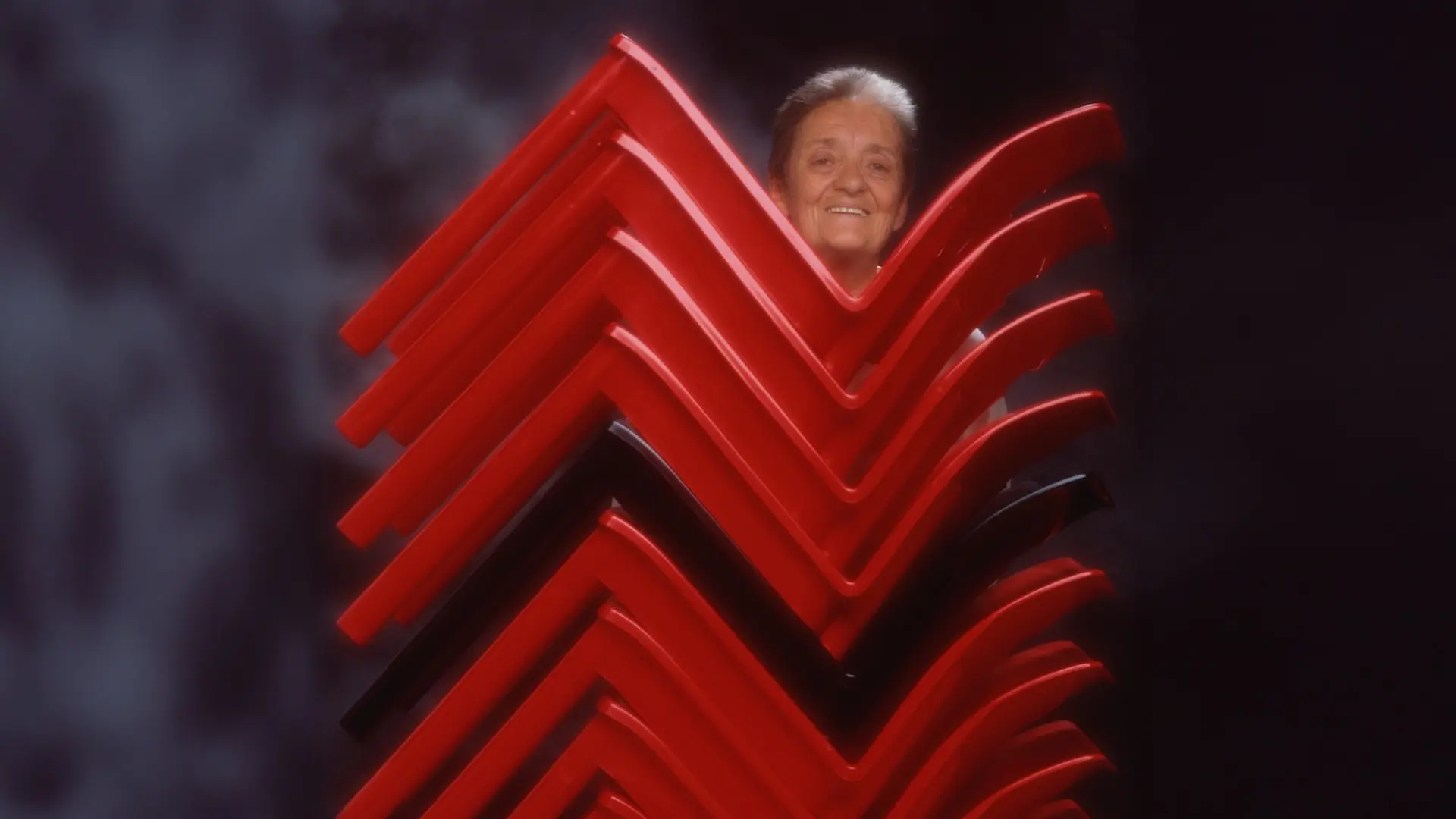

Spatial Habitats: cabinets and containers to store objects in zero gravity

Space4InspirAction with Foscarini. 4th edition 2020, Scuola del Design, Politecnico di Milano

A journey through science fiction, technology and space style, with design making a strategic and fundamental contribution to quality of life

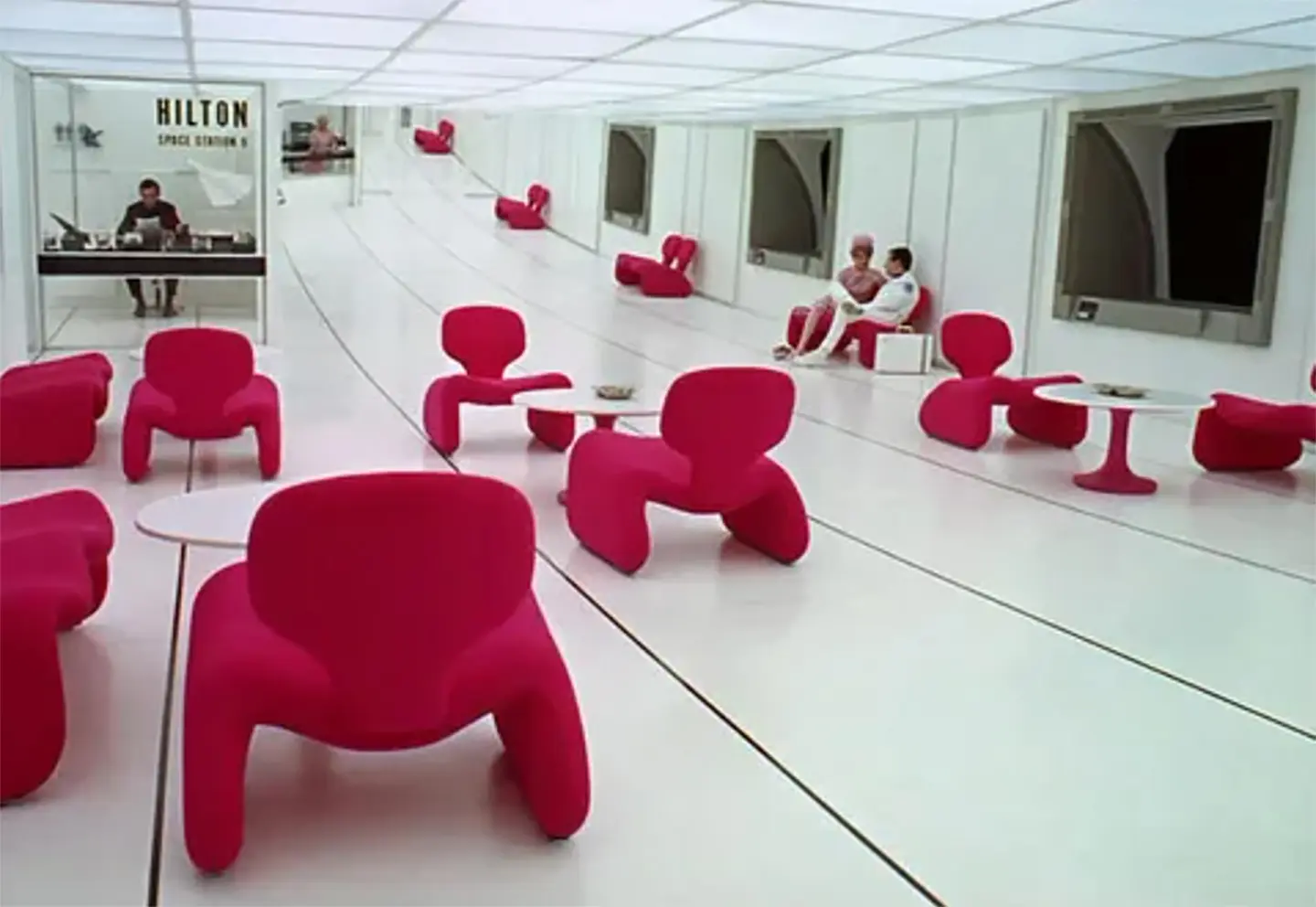

The interiors of the International Space Station (ISS) are a far cry from evocations in science fiction films whose iconic designs strongly characterized our perception of the space age. Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey featured Mourgue’s red Djinn armchairs and white Saarinen tables to create a perfect, aseptic future in which the proportions of objects and space perspectives created an aesthetic that combined technology and beauty.

The contrast could not be more stark with the real, confined, reduced-gravity spaces in which astronauts live out their daily lives on board the ISS, where there are no such thing as directions, and no up and down. The walls are covered in racks, containers full of equipment for space station maintenance and performing scientific experiments, tools for prepping, consuming and storing food, a personal hygiene module, plus a sleeping bag-equipped cabin, in which the sleeping bags must be tightly lashed down to sleep.

The racks are a tangle of labels, cables, objects, laptops and restraints, handrails that astronauts use to anchor themselves. Given the living modules are just two meters wide by five meters long, and that objects must be lashed down or they’ll float around and fill any empty space, it’s easy to understand that our perception of these spaces is of extreme chaos and disorder, and that’s even before the constant background hum of air conditioning.

Djinn chair, design Mourgue, 2001: A Space Odyssey

For all these reasons and more, in space planning design is vital to ensure high-quality environments for scientists, astronauts and – in the near future – private sector space tourists. Science fiction can inspire the conception of such projects: a number of writers and film directors have intuited future visions that have more or less come to pass, one example being the iPad-like tablet from 2001: A Space Odyssey (back in 1969).

With SpaceX astronauts wearing ultra-modern designer black and white uniforms and looking like Star Wars characters, we are potentially entering a second space age. A new avant-garde may be on the cards, as design combines know-how and research with well-being and sustainability to create sensory environments and find innovative solutions for extra-terrestrial living.

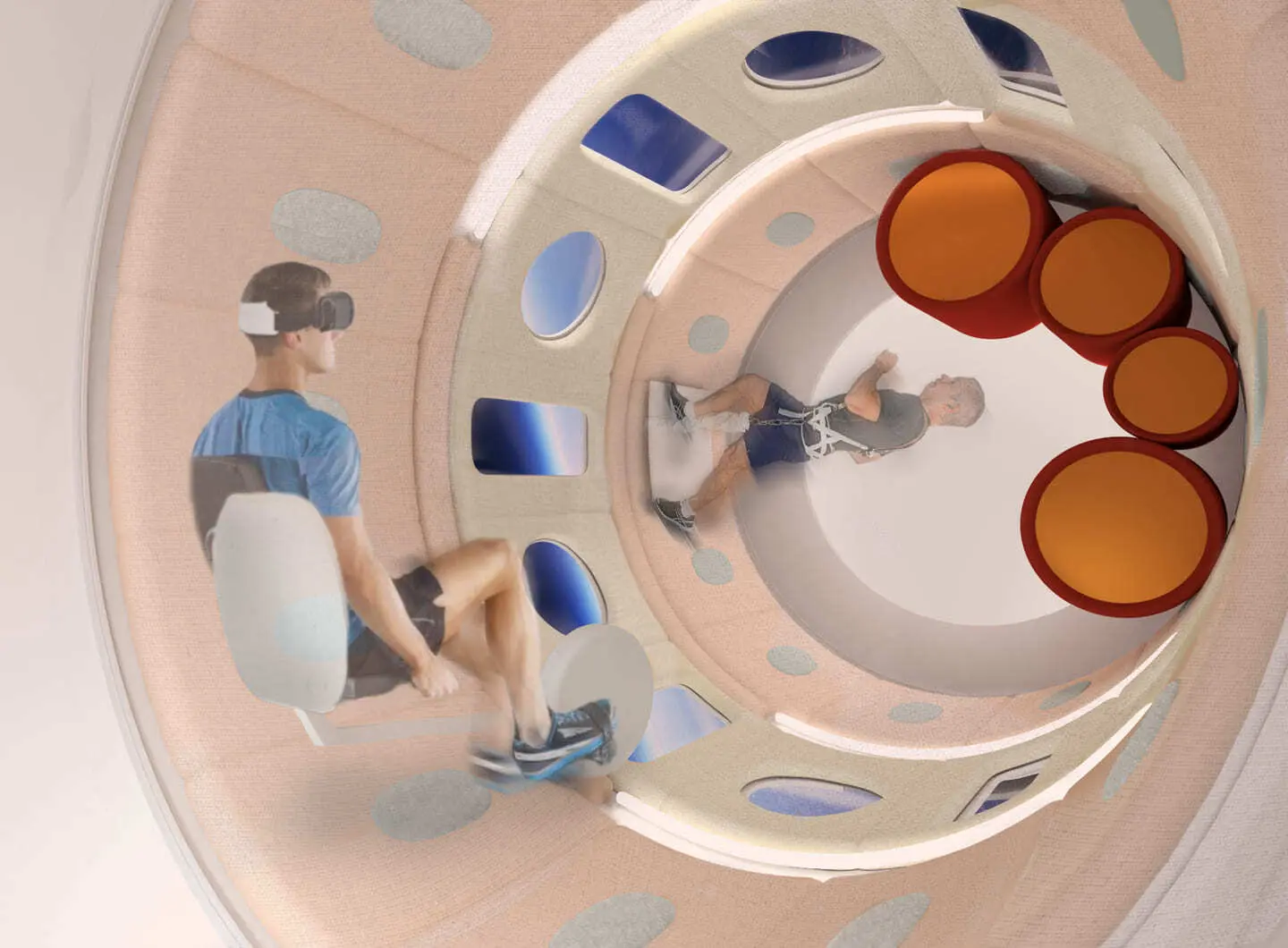

We strive to go beyond functional aspects in our spatial architectural designs, taking into account physiological and emotional elements that greatly influence human behaviour. For instance, in our latest concept for a new space station commissioned by Thales Alenia Space, one that for the first time features a whole living module entirely dedicated for crew entertainment, we worked a great deal on quality of light, not just to balance circadian rhythms altered by a lack of natural stimuli, but using light to create different areas and atmospheres within the same space depending on activities.

Another example of sensory design is being attentive to materials used to clad living module interiors, adopting visual and tactile features to make the space more welcoming and less aseptic, thereby rendering crew activities more comfortable and enjoyable. Air quality is also important, as are acoustics and reducing background noise – there is much to be done to improve these aspects in space.

The new space station designed by Thales Alenia Space is an example of the strategic contribution design can make to space planning, acting as the cutting edge in building a bridge between science, technology and beauty through its ability to predict new behaviour, acts and scenarios in unknown conditions never before experienced by human beings.

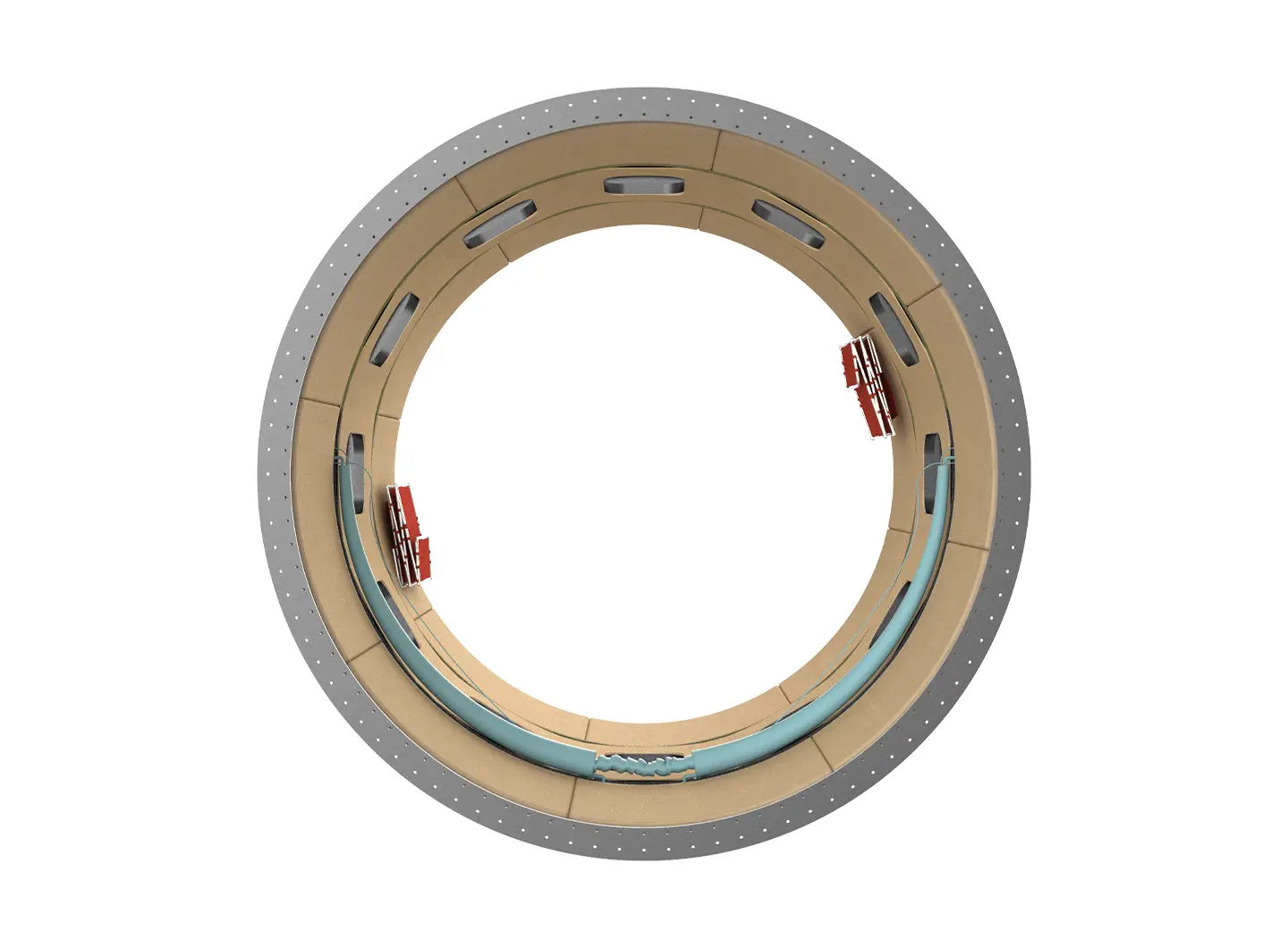

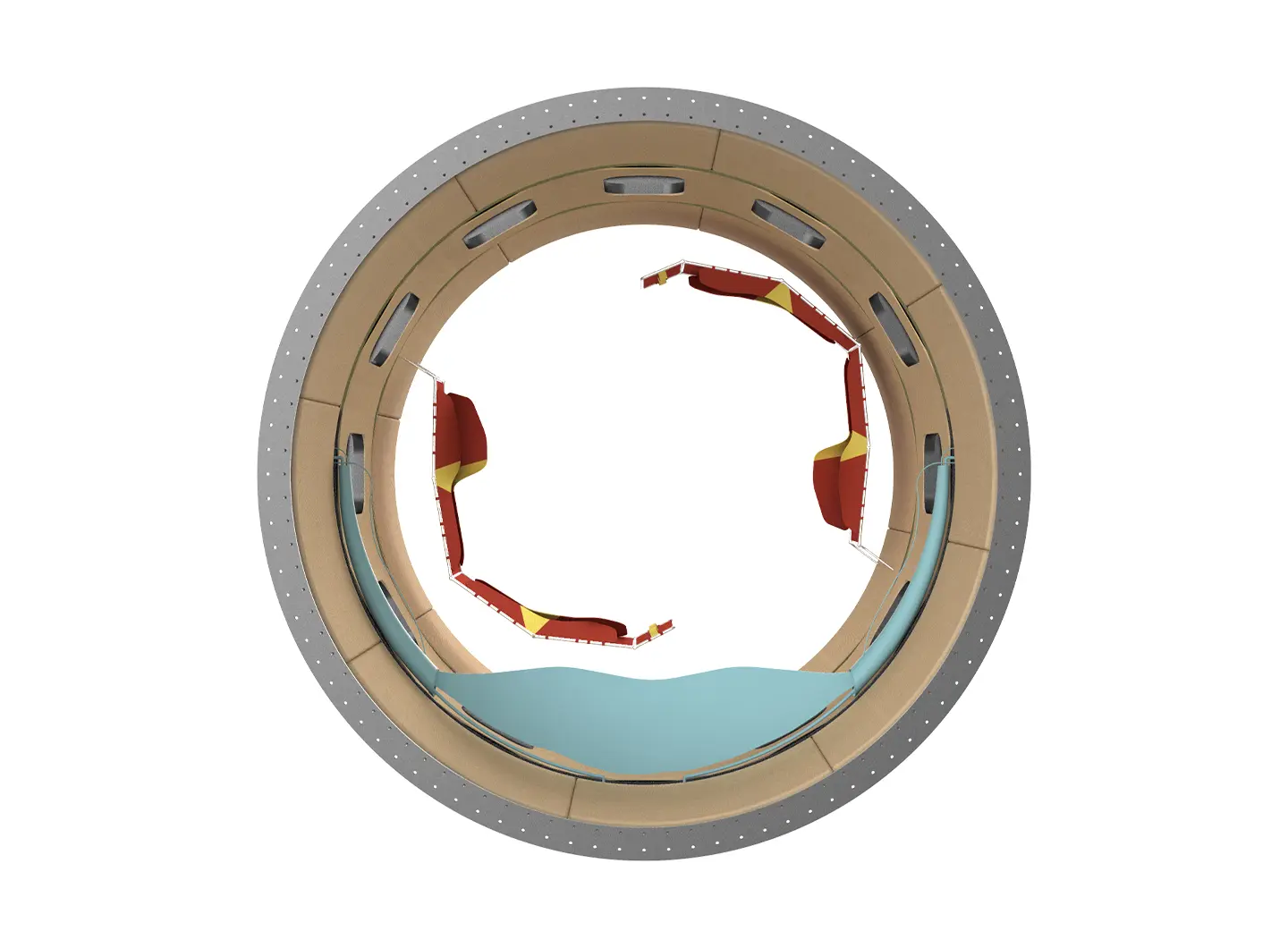

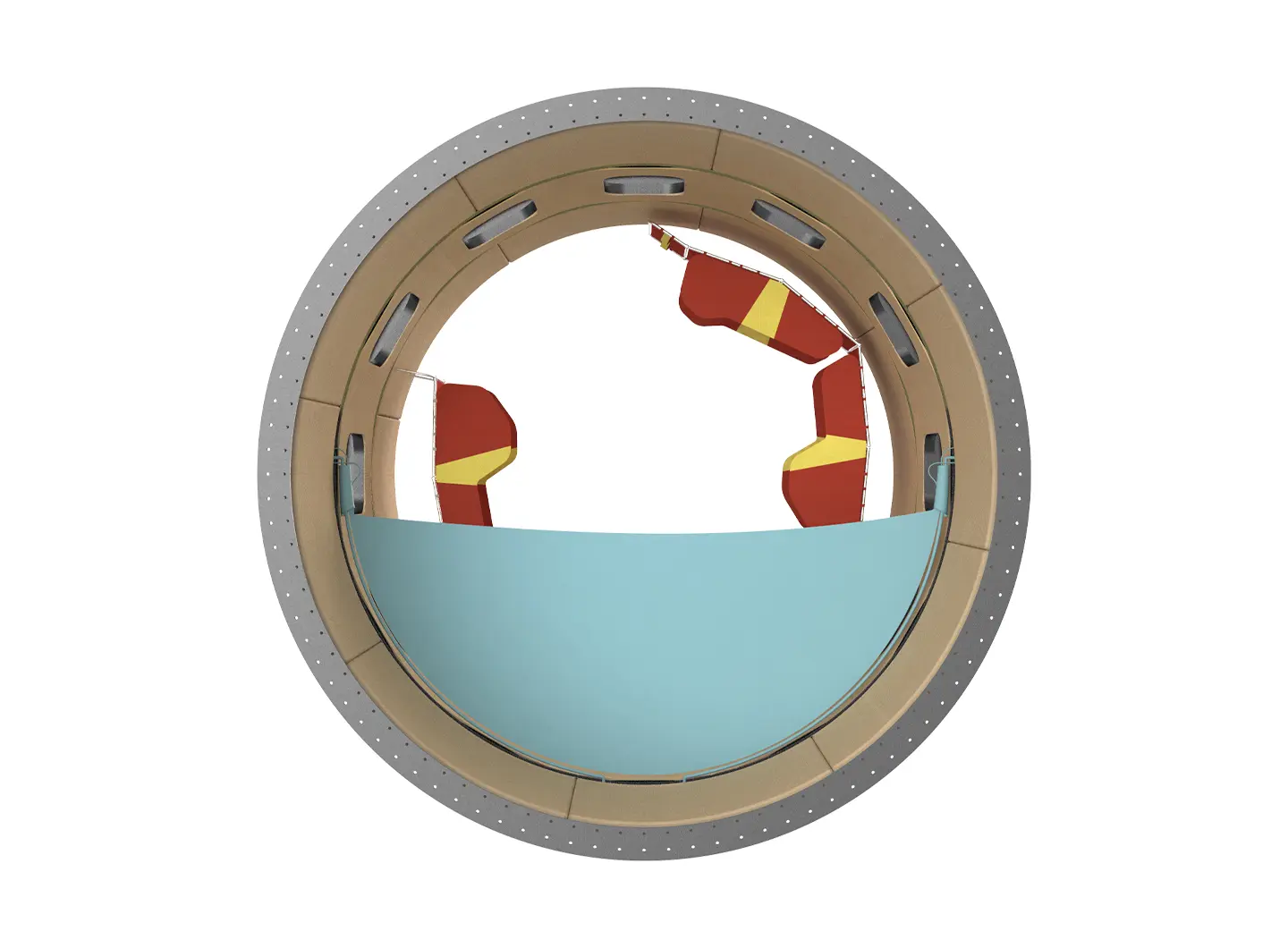

One interesting area is re-designing racks, the space cabinet/containers we have sought to combine with ergonomic features, crew comfort and efficiency under microgravitational conditions, optimizing space usability while creating reconfigurable solutions that deliver lightness and flexibility.

Tube Chair, Joe Colombo

The recreational/living module has an avowedly “Made in Italy” style that was specifically requested: in space as on Earth, Italy is synonymous with beauty and quality. It was natural for us to hark back to 1960s Italian design, revolutionary not just in terms of style but technological innovation, at a time when new plastics made it possible to create soft, organic shapes that had previously been impossible to manufacture, generating cheap, light and adaptable objects.

Working on our entertainment module design, we considered the variety of activities astronauts might perform: working, relaxing, reading, playing and listening to music, resting, looking out the windows, holding meetings and eating together.

That said, given that space in all modules must be totally unimpeded for safety reasons, we had to come up with a mobile solution: a folding fabric partition to create temporary closets or relaxation rooms, equipped with a folding chaise longue anchorable to the module’s structure. Flexible Velcro restraints on the seating makes it possible to maintain bodily posture; indeed, Velcro adorns all of the soft surfaces on the module’s inner lining to allow the crew to move around or stay in one place as required.

The chaise longues are composed of cylindrical volumes that offer the advantage of interior space. They may be converted into removable containers and shelving to stow scientific equipment and instruments, a quote to Joe Colombo’s science fiction Tube chair, the space-saving object par excellence.

Stories

Stories