Gio Ponti amid architecture, design and industry: from the Pirelli skyscraper to Domus, to furnishings reinterpreted through archival work

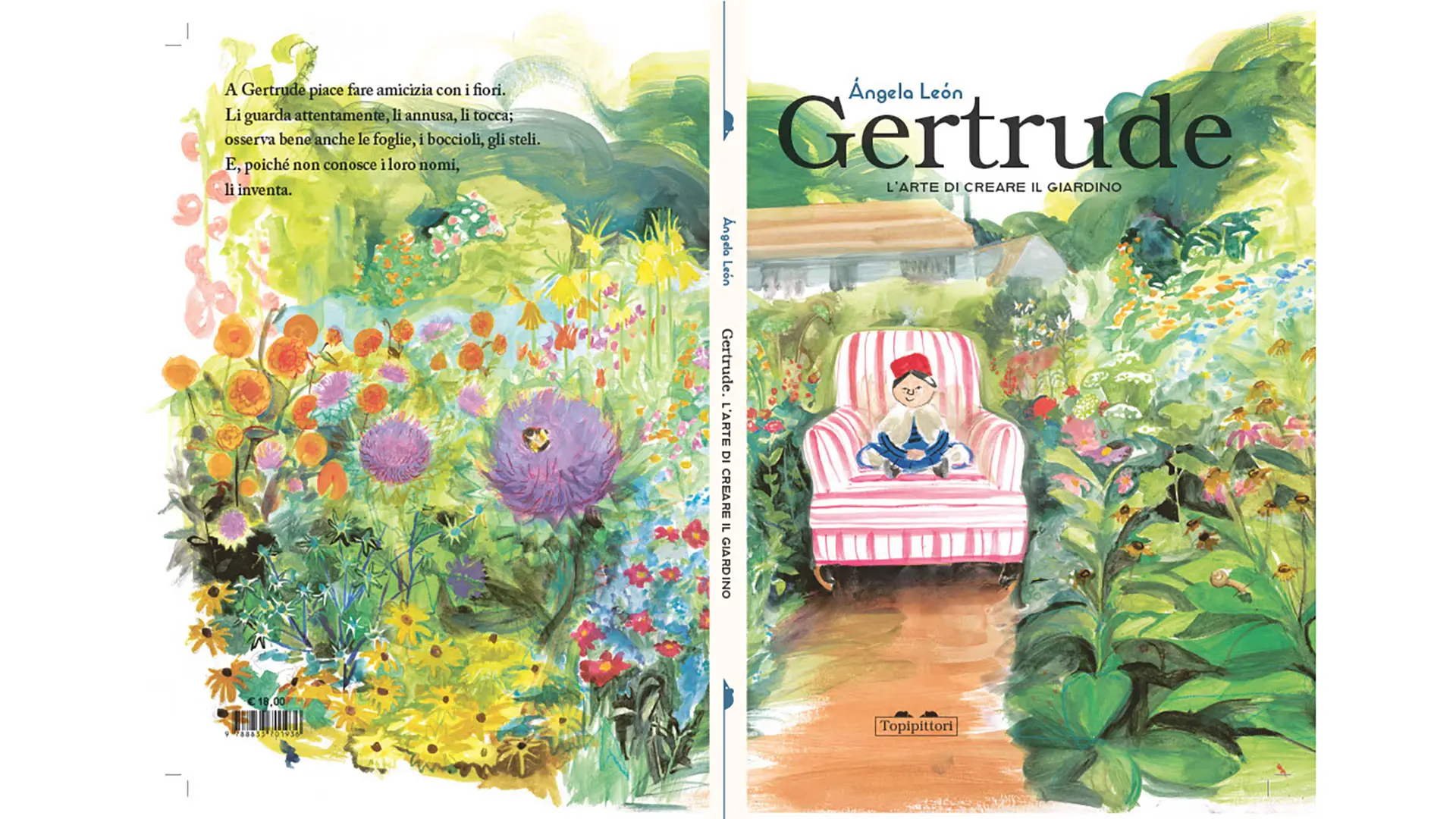

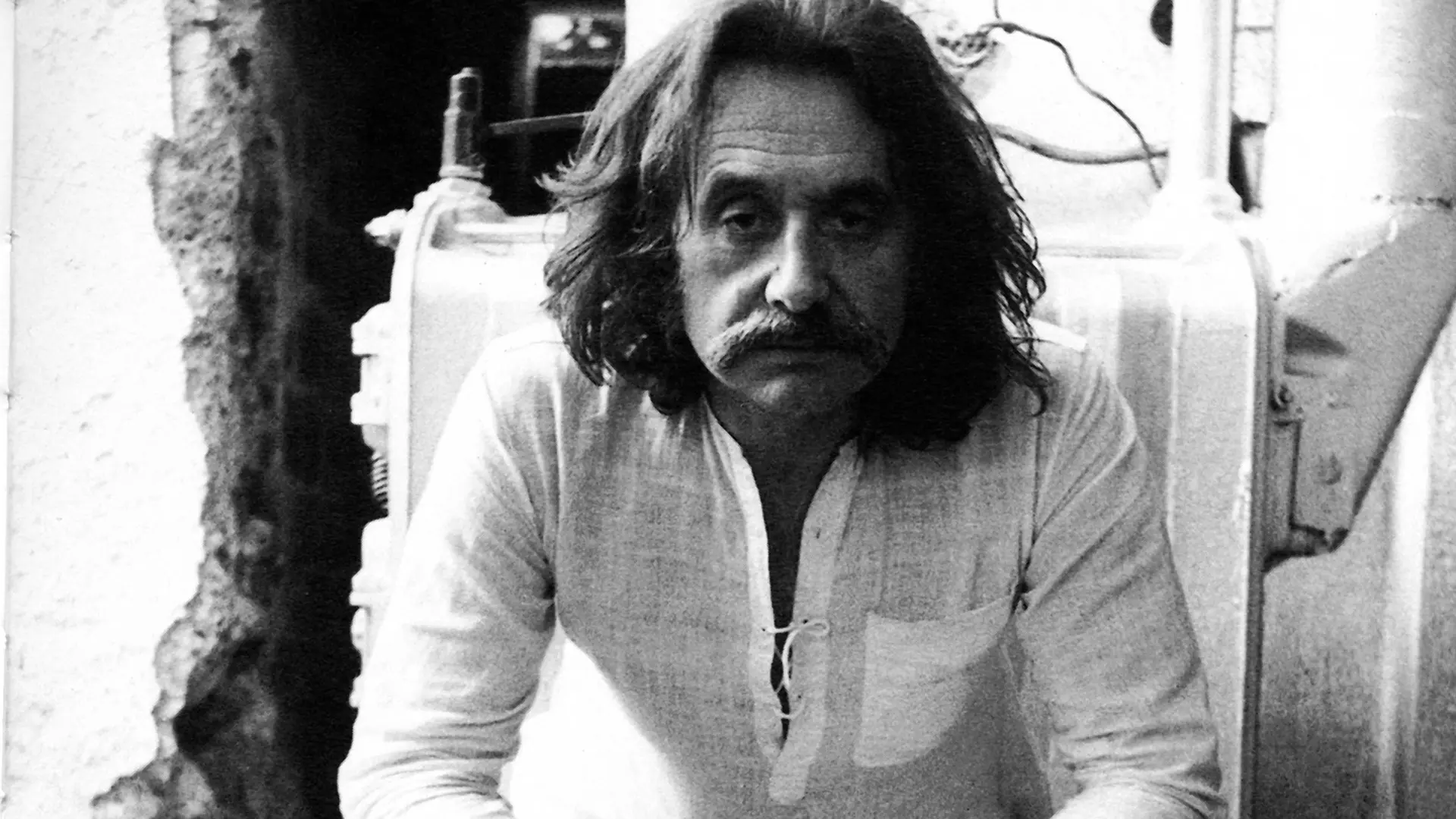

Ettore Sottsass,Promoted by Cosmit and Organized by iSaloni spa on the occasion of the Salone Internazionale del Mobile – april 1999

The career of Ettore Sottsass Jr. is distinguished by his absolute multifacetedness. Architect, artist, designer and writer, during the early 1960s he started creating “ornaments” for the human body, jewellery that became a sort of three-dimensional translation of the pleasure of rediscovering one’s existence through contact with an extraneous object.

We’ve been used to calling the great Ettore Sottsass Jr., one of the most influential and multifaceted designers on the global design scene, active during the second half of the 20th century, a “master” for almost fifty years. He and his unique sense of humour, continue to be an eternal and constant point of reference for the upcoming generations, who find something of themselves in Ettore, the architect, artist, designer, draughtsman and writer. Of all the many Ettores, today we would like to remember Ettore the jewellery designer, who knew how to encapsulate the image of a society he did not necessarily identify with in a decorative object. Even as far back as the early 1970s onwards, Ettore Sottsass Jr. started designing “ornaments” for the human body, not so much for aesthetic purposes as for his own personal approach to the theme of social vindication. For Ettore, designing jewellery meant sending a very precise message, a political message destined to go straight to the hearts and minds of those encountering the person wearing it in the street, in the bar or in the pharmacy. The person who wore it, of the female gender, became a sort of manifesto for the designer’s mindset, publicly demonstrating their adherence to his political stance. This triggered a whole series of pieces which, as Sottsass wrote in Domus in 1968, raised a question that “went much further than it might seem.”[1]

Ettore Sottsass, collana, 1985 and collana pendente figura, 2002 Courtesy Cleto Munari

He went on to say: “the question ought to fly gently above the silent, grim, rabid proletarian competition, above the small, petulant, acid middle class competition, above the great, thin, consequential competition of the fat cats and also above the arrogant, cowardly and poisonous competition of the intellectuals, coming to rest on those cushions where femininity is inexplicable and unexplained, where women have a way of doing and being that is impossible to fathom why and how.”[2] It wasn’t simply a political issue for Sottsass, nor one of class, it was a question of freedom. These ornaments were intended to globally unite every woman on Planet Earth, from the Amazon to the Parisienne, and were aimed above all at women who rediscover their levels of freedom in a profoundly damaged society and in the name of love. They are pieces for women who are “real, crazy, unfathomable, antisocial, lost and alone, lovers in love affairs that slide into madness or love affairs that have ended badly, who knows: the ornaments must end up somewhere there – rather like a token of love, love, serious love, cosmic love, a bit like an offering for a passionate journey in life, a bit also like a sign of pity for the bodies that engender love and then lose it, they shine brightly and then become dimmer, they find arms for being embraced and then remain alone, abandoned for ever.”[3]

This was one of Sottsass’s great ambitions and one that he was to return to years later, towards the end of the 1980s, when Cleto Munari asked him and other extremely prominent designers to design jewellery for him. He then reverted to describing ornaments for the human body as a primitive form of clothing that had indissolubly linked every population since the Ancients. He achieved this through the creation of objects encapsulating this message, becoming a sort of three-dimensional translation of the joy of rediscovering one’s own existence through contact with an extraneous object. Sottsass attributed a magical importance to these pieces, which were the upshot of a logical and conceptual process, redolent with symbolism and meaning. Over the years he continued to design jewellery, timepieces and designer objects for Cleto Munari, the master of the art of jewellery design as well as a great entrepreneur and patron. Necklaces made of wood, rings suggestive of deconstructivist architecture, earrings drawing on primordial memories - all these objects were conceived and designed by Sottsass, drawing on anthropological and social principles, and chiming with his idea of love, which was so idealised as to seem almost unsettling. But it’s not right to put up with mediocre things. As he said himself: “the savannah knows no borders: we’re all in it together.”

Ettore Sottsass, bague (or, corail), 1967. Courtesy Cleto Munari

[1] E. Sottsass Jr., Sono Mille Volte Meglio gli Ornamenti dei Nomadi del Sole, in Domus, no. 464, July 1968, p. 39.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

Stories

Stories