Setsu & Shinobu Ito

Setsu & Shinobu Ito

Partners in life and work, their work ranges from architectural to interior and industrial design, craftsmanship, packaging, and electronics informed by a blend of Japanese and Italian culture.

Milanese by adoption, they both attended university in Japan - Setsu graduated from the University of Tsukuba and Shinobu from the Tama Art University in Tokyo. Setsu started working with Alessandro Mendini at Studio Alchimia, and then with Angelo Mangiarotti, while Shinobu’s career began at CBS Sony (Sony Music Entertainment) - Sony Creative Products, following which she took a Masters from the Domus Academy in Milan, and then worked in the fields of design and marketing. Partners in life and work, they set up their design studio in Milan in 1997 and have been working and carrying out crosscutting consultancy work for international clients since then, ranging from architectural design to interior and industrial design, craftsmanship, packaging and electronics. They have both also been invited to teach at leading design schools, including Domus Academy in Milan, Milan Polytechnic University, the IUAV in Venice, the IED in Milan, as well as the Tama Art University, the University of Tsukuba and the University of Tokyo, in Japan.

What sets them apart is their blend of their original Eastern culture and the Western culture they have acquired over the years, which generates fluid, flexible shapes.

The word “design” has become a word that is used in all aspects of society and the areas in which design has to be applied are growing from year to year. We have worked on a vast range of products, not because of these prospects but because of our roots. It’s the way Italians used to think about “Design”, where designers work round all the themes and come up with solutions. We regard ourselves as designers in the round. I think the role of global designers will expand in the future in a complex society such as this.

It wasn’t random by any means. Setsu was greatly influenced by his father, a sculptor, who had been strongly attracted to Italy since childhood, and by a young Italian teacher he met while he was at university. Shinobu, on the other hand, was hugely influenced by Postmodern Italian design during the ‘80s, when she was at university. Milan, Italy, have a design feel, which is much more palpable than in Japan, and means that we’re lucky enough to be able to constantly try out new things, with innovation taking priority over commercial gain.

They’re both wonderful and it’s amazing to be able to design and to live experiencing them both. They don’t conflict. You could say that Eastern culture is nature-focused, while the other is people-focused. In the East, too, the Japanese culture is closest to nature, we observe and consider the harmony between nature and science. On the other hand, of the Western cultures, Italy is the one that has pursued the essence of humanity to its very core, including its weak points, because it’s the origin of man-centred culture. At first glance, the two cultures seem to be in harmony and to dovetail. Looking to the future and thinking around harmony with the natural environment and the inclusive harmony of human society, the two cultures are equally important, and I think this is how we’ll create even greater value.

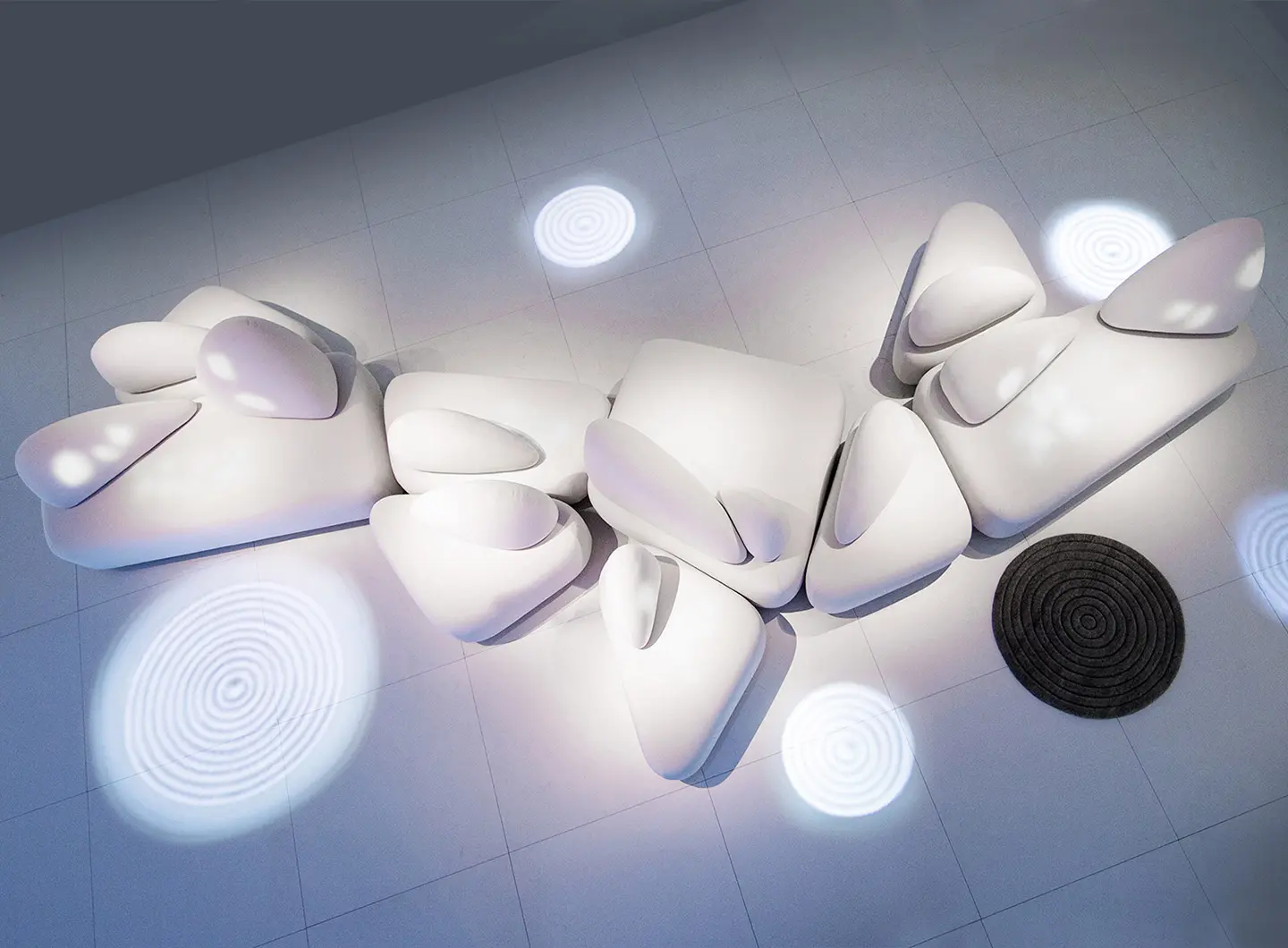

Being interactive and modifiable is one of the major values of design today. Interactive design doesn’t just stop at designing electronic devices. The significance of furniture and accessories, which don’t move or change, will depend on the relationship between the people and places involved. Because of the nature of wood, walls are temporary partitions in Japanese architectural culture, based on columns and frame constructions, and the function and size of a space can be different each time. One of the major indicators of our design work is enabling the user to change shapes and expressions.

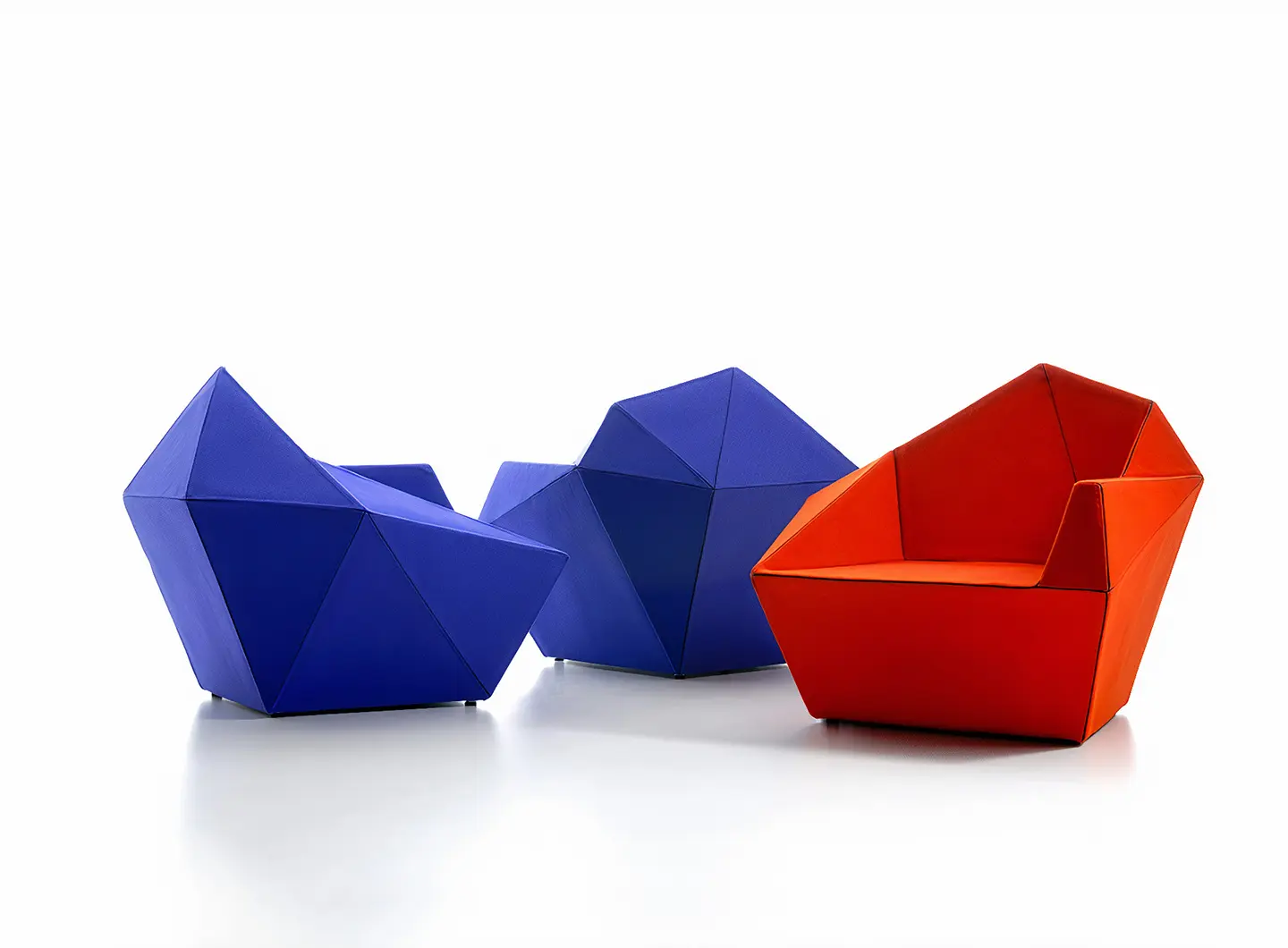

The balance between symmetrical and asymmetrical beauty is important. The beauty of the Japanese culture is the asymmetric beauty of calligraphy and the Katsura Imperial Villa. We carry out projects that aim for the beauty of symmetry, but when we do asymmetrical designs, we’re aiming for an exquisitely balanced, powerful kind of design.

It’s useful to compare the Eastern and Western cultures by comparing two natural materials: paper, light and two-dimensional and stone, heavy and three-dimensional. Sometimes we use the paradox of solid, heavy paper and light stones. We’re interested in paper, wood, metal, glass, stone and, practically, all natural materials. More specifically, we’re interested in how all natural materials can be used as sustainable materials. The important task for design in the future is to purify natural materials that are thrown away and used as secondary regenerated waste materials, harnessing science and technology to turn them into splendid design products.

These concepts are the five pointers we’ve identified over many years of comparative study of Eastern and Western design and they equate to the five fingers of the creator. The first finger, Space Rhythm / Microcosm, expresses the idea that the universe and nature are all around us and that we are part of them. The concept of design is to feel the rhythm of the universe and of nature through space, from the furniture to the accessories you design. The second finger, Sensescape / Earth/ tactile, is a concept derived from the Japanese tradition of taking off one’s shoes and sitting down on the floor. Since we were born from the earth and have grown from the benediction of the earth, this concept underscores the desire to maintain contact with the earth, the desire to come together and the importance of the sensation of touch. The third finger, Emotional Island / relationship, is a design concept in which Sukiya = empty space in Japanese architecture, as mentioned previously, can be used to create alterations, timescales and places according to need. The fourth finger, Unconscious Polyhedron / Hidden / unconscious, relates to the Eastern concept of space, which separates interior from exterior, “visible and hidden,” with various intermediary woven structures, such as Japanese folding screens, hanging screens, goodwill, willingness, sliding doors, porticoes and thresholds. This concept blends the multidimensional concept of space with the beauty of the multidimensional and complex modelling found in nature. The fifth finger, Leaf Solid / materiality, is a concept that shows the process from surface to solid as represented by Japanese origami, based on the comparison of East-West paper and stone. The kind of design that quite clearly adopts the opposite process to the West: point → line → plane → module is used to express Japanese artistic beauty.

Design style will be repeated, but demand for design will become increasingly diversified, with design applied to everything and to phenomena beyond space and furniture. While everyone will be talking about design, I think design skills in the round and the flexibility of professional designers will become increasingly important. It will be like the Italian design of the past, of 50 years ago, or rather 500 years ago (laughable).